by Jochen Markhorst

- Million Miles part 1: The closer I get, the farther away I feel

- Million Miles part 2: They kind of write themselves

- Million Miles part 3: And thou didst commit whoredom with them

I’m drifting in and out of dreamless sleep Throwing all my memories in a ditch so deep Did so many things I never did intend to do Well, I’m tryin’ to get closer but I’m still a million miles from you

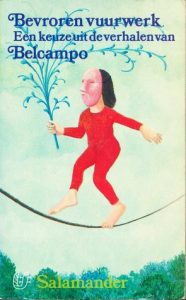

Within the Dutch literary landscape, Belcampo (1902-1990), with his remarkable, fantastic, magical-realist works, is an odd man out; he has no predecessors and no followers, and remains a separate movement on his own. Internationally, he is somewhat comparable to Roald Dahl, to Murakami perhaps, to Petrushevskaya in a way… but above all: unique. A man accidentally cuts off his own index finger, doesn’t know what to do with it, and finally decides on an impulse to bake it and eat it. “When I had eaten it, the discovery had been made: the discovery that no enjoyment on earth can compare to eating your own flesh.” He becomes addicted to his own flesh, eats all his limbs in the following months and now needs the help of his friend the doctor to amputate and eat his last remaining limb, his right arm (Page From The Diary Of A Doctor, 1934). King Wurm forbids his people to dream. They are only allowed to drift in and out of dreamless sleep. His people revolt, behead him, but a surgeon manages to connect his head, the head of state as it were, to a device and keep it alive (The Triple Combination, 1934).

Within the Dutch literary landscape, Belcampo (1902-1990), with his remarkable, fantastic, magical-realist works, is an odd man out; he has no predecessors and no followers, and remains a separate movement on his own. Internationally, he is somewhat comparable to Roald Dahl, to Murakami perhaps, to Petrushevskaya in a way… but above all: unique. A man accidentally cuts off his own index finger, doesn’t know what to do with it, and finally decides on an impulse to bake it and eat it. “When I had eaten it, the discovery had been made: the discovery that no enjoyment on earth can compare to eating your own flesh.” He becomes addicted to his own flesh, eats all his limbs in the following months and now needs the help of his friend the doctor to amputate and eat his last remaining limb, his right arm (Page From The Diary Of A Doctor, 1934). King Wurm forbids his people to dream. They are only allowed to drift in and out of dreamless sleep. His people revolt, behead him, but a surgeon manages to connect his head, the head of state as it were, to a device and keep it alive (The Triple Combination, 1934).

The Roller Coaster (“De Achtbaan”) from 1953 is set in a near future, in 2050, in which science not only manages to erase memories, but even to transplant them; someone’s memory, or selected parts of it, can be transferred to someone else’s brain – which then integrates it as its own memories. A topic that Philip K. Dick will borrow for his story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale (1966), of which director Paul Verhoeven will then make the hit film Total Recall in 1990. In Belcampo’s tale a market of supply and demand soon emerges;

“Now, for the first time, one could see how great the dissatisfaction with this life was that prevailed among people, and it also appeared that this dissatisfaction was due much less to the presence of happiness-inhibiting complexes than to the absence of gratifying and blissful images.”

The story then centres on a couple who want to remove their memories of each other. Yes indeed, the same plot as in the brilliant 2004 film Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind by Charlie Kaufman – with an identical ending too, by the way.

Belcampo, Charlie Kaufman, Philip K. Dick, Paul Verhoeven… they all vary on the lament of Dylan’s protagonist in “Million Miles”, on the fantasy how liberating it would be to throw all my memories in a ditch so deep. Oblivion as a healer of the tormented soul, ignorance is bliss, or, as Alexander Pope put it in 1717, the eternal sunshine of the spotless mind (from “Eloisa to Abelard”).

The mourning protagonist consciously seeks the ultimate state of denial, the first stage of any grieving process: he longs for a state in which he does not dream of her, cannot remember her… for the non-knowledge that she exists. But already in the third verse he seems to recognise the impossibility thereof; with the self-reproach Did so many things I never did intend to do he signals guilt, and thus already switches to the next phase of mourning. And immediately afterwards he shifts gear forward to the next phase:

I need your love so bad, turn your lamp down low I need every bit of it for the places that I go Sometimes I wonder just what it’s all coming to Well, I’m tryin’ to get closer but I’m still a million miles from you

… to depression. For which the songwriter can blindly dig into the blues grab bag; after all, three-quarters of all blues songs are about heartache – the canon offers an abundant choice of appropriate jargon. Dylan doesn’t grab too deep. “Need Your Love So Bad”, Little Willie John’s immortal pièce de résistance from 1955 is somewhere at the front of the canon, especially after Fleetwood Mac’s, or rather Peter Green’s upgrade of the song in 1968. With indirect input from Little Willie, by the way; the string section for Fleetwood Mac’s single was written by Little Willie’s guitarist, the legendary Mickey Baker, at the request of producer Mike Vernon.

At least as famous is the next borrowing, turn your lamp down low;

Wake up, mama, turn your lamp down low Wake up, mama, turn your lamp down low Have you got the nerve to drive Papa McTell from your door?

… Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues”, which is perhaps even a few steps higher up in the Pantheon. Blind Willie recorded the song as early as 1928, Taj Mahal made it popular again in 1968, and with their live version from 1971, The Allman Brothers elevated “Statesboro Blues” to the canon once and for all. On At Fillmore East, with a Duane Allman, shortly before his death, at the top of his game.

The meaning of the phrase turn your lamp down low is somewhat diffuse, though. And Dylan, too, seems to prefer to keep it a bit vague. Blind Willie probably heard it from Bobby Grant, who a year earlier recorded his “Nappy Head Blues”, with the opening lines When you hear me walkin’, turn your lamp down low / And turn it so your man’ll never know – in which “turn your lamp down” apparently means something like an invitation to adultery. But then, when Big Joe Williams takes the phrase in 1935 to the song that will also achieve such monumental status, to “Baby Please Don’t Go”, the meaning shifts to its opposite;

Turn your lamp down low You turn your lamp down low Turn your lamp down low, I cried all night long Now baby please don't go I begged you nice before I begged you nice before I begged you nice before, turn your lamp down low Now, baby please don't go

… and seven more verses similar in content – the man begging his woman to remain faithful, to not let other men in; turn your lamp down low now meaning something like “keep your sexual urges under control”.

https://youtu.be/g22l1hnAnlA

In Dylan’s “Million Miles” it can mean both. “I need your love so bad, let me in”, or “I need your love so bad, don’t give it to another”. But the poet decides on playing with words, insinuating he needs both her love and her lamp: I need every bit of it for the places that I go – I’m entering a dark period, I may need some love and some light, so we have to be sparing with the lamp oil, something like that. Not too strong, but a signal that we are reaching the final stage of the mourning process: acceptance.

Yeah well. Sometimes I wonder just what it’s all coming to, one would be inclined to think.

To be continued. Next up Million Miles part 5: The sounds inside my mind

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang