by Jochen Markhorst

I Dreamin’ of Henry

Just like the equally compelling time document The Bootleg Series 12 – The Cutting Edge 1965-66 (2015), on which we can voyeuristically follow the evolution from run-up to final studio recording (such as the twenty takes of “Like A Rolling Stone”), the brilliant The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006 from 2008 does give us a glimpse into the phase before as well, into the sketchbook, into the process of coming up with a lyric. We hear how lines and word combinations from the rejected “Marchin’ To The City” are transferred to “Not Dark Yet” and “‘Til I Fell In Love With You”, and we get alternative recordings with textual differences (“Born In Time” and “Dignity”, for example).

Just like the equally compelling time document The Bootleg Series 12 – The Cutting Edge 1965-66 (2015), on which we can voyeuristically follow the evolution from run-up to final studio recording (such as the twenty takes of “Like A Rolling Stone”), the brilliant The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006 from 2008 does give us a glimpse into the phase before as well, into the sketchbook, into the process of coming up with a lyric. We hear how lines and word combinations from the rejected “Marchin’ To The City” are transferred to “Not Dark Yet” and “‘Til I Fell In Love With You”, and we get alternative recordings with textual differences (“Born In Time” and “Dignity”, for example).

The rejected outtake “Dreamin’ Of You” offers the same insight as “Marchin’ To The City”, and more: apart from the gems Dylan picks out to use for other songs, it seems to reveal what a very first seed for a Dylan lyric can be. At least, that’s what the opening lines appear to give us, the opening which will eventually, after the rejection, be transferred to “Standing In The Doorway”:

The light in this place is really bad Like being at the bottom of a stream Any minute now I’m expecting to wake up from a dream

The opening line, as Dylan researcher Scott Warmuth found, is lifted in its entirety from Henry Rollins’ poem “One Way Conversation” (in See A Grown Man Cry, 1992);

Yea, hi I thought I'd check in This house I'm at is full of bugs There's lots of things that I don't tell you Lots of things that don't have words to wear The light in this place is really bad I'm thinking about your eyes Hell, we're tied up in this shit you know Stuck behind walls, frozen in doorways I hope these bugs don't get into my food

… and from the remaining eight lines, which are similar in content, it becomes clear that the narrator is talking to an answering machine and is in a slightly detached state; he does not know exactly where he is, for example. Somewhere halfway through, there is then the line that Dylan has underlined, “The light in this place is really bad”, and which initially inspires him to the somewhat alienating, and in any case original metaphor, “Like being at the bottom of a stream”. Alienating, because few listeners or readers will have an aha-experience with “the light at the bottom of a stream” – given that a metaphor is actually meant to make something clear by naming a resemblance to something familiar. But then, of course, this characteristic does not apply so much to poetry. And to an even lesser extent to Dylan’s poetry.

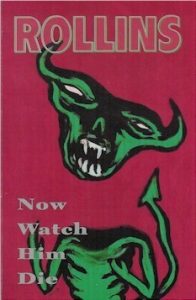

“Being at the bottom of a stream” forces the associations to lugubrious distances, as a matter of fact. It is a location where we find victims of a witchcraft trial, where Ophelia ends up after her suicide, it is a classic dumping ground for murder weapons whose owner wants to get rid of, and more macabre connotations just like these – but there are really no positive links with a river bottom. The gloominess is triggered, presumably, by the morbid Now Watch Him Die, the 1993 work in which Henry Rollins processes the horror of the gruesome, senseless murder of his friend Joe Cole (who is shot through the head point-blank right before Henry’s eyes in a brutal robbery). Dylan incorporates more fragments from that chilling work into his Time Out Of Mind songs, like in this stanza; the fourth line, “I’m expecting to wake up from a dream”, is also taken from Now Watch Him Die:

“In semi-darkness I think about my friend. In a few days it will be a year since his death. I remember when it was a week. I sat behind the desk of the office space I was living in and I was amazed at how unreal the entire week had been. I kept expecting to wake up from it like a dream.”

… whereby Dylan will have poetically associated the setting, in semi-darkness, with that other Rollins quote The light in this place is really bad – and the morbid context might then trigger the sinister décor, the bottom of the stream.

In any case, the continuation of this first stanza confirms that we should not understand the title Dreamin’ Of You romantically, not as the title of a love song:

Means so much, the softest touch By the grave of some child, who neither wept or smiled I pondered my faith in the rain I’ve been dreamin’ of you, that’s all I do And it’s driving me insane

…the grave of “some child”, a crisis of faith at a funeral in the rain, the longing for a comforting hand – this is the despair of a narrator left behind after the death of his loved one. With similar word choice and identical emotion as one of Bob Forrest’s (well, officially The Bicycle Thief’s) most beautiful, raw mourning songs “Everyone Asks” from 1999, in which he poignantly tries to come to terms with the death of a loved one almost a year ago:

Why do I always Call your name If it doesn't stop I'll go insane I just know

https://youtu.be/8ztUSXZw2bg

Wonderful song by the devout Dylan fan Forrest, in whose work we hear more Dylan echoes – although usually more raw, more unadorned than at Dylan, of course. Dylan, meanwhile, is apparently also pleased with the word combinations in this first stanza: after the song’s dismissal, the line “means so much, the softest touch” moves to “Standing in the Doorway” as well (as “Dreamin’ Of You” will be the purveyor of the lyrics to that song anyway).

For the colour of his song the poet aims, or so it seems, at the nineteenth century, at “steamboat, civil war, very Mark Twain,” as guitarist Duke Robillard would say about that other discard, “Red River Shore”. The grave of a child is already a Chekhovian background, the disturbing character description who neither wept or smiled seems to come from Henry James (“she only looked at him silently in return, neither weeping, nor smiling, nor putting out her hand,” Madame De Mauves, 1874), and pondering faith in the rain is a rather Walt Whitman-like image.

It appears, all in all, as if Dylan has ticked those two Rollins lines, and then opened the floodgates. In the run-up to Time Out Of Mind, he has already dug a bed, the nineteenth-century steamboat, Mark Twain bed, and inspired the stream of consciousness leads him along Checkhov, Whitman and Henry James, along nineteenth-century word combinations and images to be found at the bottom of this stream. Far, far away from Henry Rollins, in any case.

To be continued. Next up Dreamin’ Of You part 2: The Lay of the Last Minstrel

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

Far beyond Rollins there too lies Edgar Allan Poe:

(Dim gulf!) my spirit lies hovering

Mute, motionless, aghast

For alas! alas! with me

The light of life is over

(To One In Paradise)

Nor can one speak of Dylan without alluding to poet John Keats.

In a long poem by Keats, a mortal who is adored by the three-spirited Moon Goddess wants to become immortal like her.

Endymion tries to quite chasing after the ideal woman, represented by the moon, but he can’t.

To escape one predicament Endymion finds himself in, he must help re-unite separated but now dead lovers:

The visions of the earth were gone and fled

He saw the giant sea above his head

(Keats: Endymion)