by Jochen Markhorst

II Oh, how I love you

In most models, the universe was filled with an enormous energy density and enormous temperatures and pressures. Filled with jump blues by men like Wynonie Harris, the songs and stage presence of Chuck Berry and Little Richard, rockabilly, Arthur “That’s All Right Mama” Crudup, bluegrass, “Ida Red” and Louis Jordan… the confluence of these leads to a sudden, violent cosmic inflation: the Big Bang of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Elvis’ debut album Elvis Presley on 13 March 1956, the first rock ‘n’ roll million seller. And the ignition of that Big Bang is Carl Perkins, or rather his song, the opening song of Elvis Presley: “Blue Suede Shoes”, with which Perkins himself had scored his first and only No.1 shortly before.

In most models, the universe was filled with an enormous energy density and enormous temperatures and pressures. Filled with jump blues by men like Wynonie Harris, the songs and stage presence of Chuck Berry and Little Richard, rockabilly, Arthur “That’s All Right Mama” Crudup, bluegrass, “Ida Red” and Louis Jordan… the confluence of these leads to a sudden, violent cosmic inflation: the Big Bang of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Elvis’ debut album Elvis Presley on 13 March 1956, the first rock ‘n’ roll million seller. And the ignition of that Big Bang is Carl Perkins, or rather his song, the opening song of Elvis Presley: “Blue Suede Shoes”, with which Perkins himself had scored his first and only No.1 shortly before.

Not a flash in the pan. After “Blue Suede Shoes” Perkins enriched us with songs such as “Matchbox”, “Honey Don’t” and “Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby”, and Sir Paul McCartney declared the official canonization: “If there were no Carl Perkins, there would be no Beatles”.

In short, the music-historical importance of Carl Perkins is difficult to overestimate; the credit Perkins has is infinite. Though he did lose a little of that credit in 1996, two years before his death. Just like Dylan said about his idol Elvis (“I never met Elvis, because I didn’t want to meet Elvis […] Because it seemed like a sorry thing to do”), you should leave your image of the extra-terrestrial Carl Perkins intact. And not pollute it with too much information.

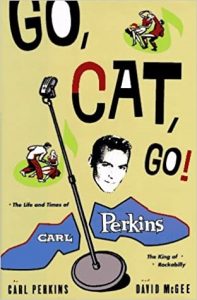

Go Cat Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly (1996) is a hybrid of autobiography and biography, written by Rolling Stone journalist David McGee. A concept that rarely works out well; a self-admiring protagonist and the uncritical admiration of the co-writer, who is almost by definition a fan, is a fatal combination. Life, by Keith Richards and James Fox, is a rare exception, and illustrates painfully clearly why the (auto-)biographies of big names like Dr. Ralph Stanley (Man of Constant Sorrow, 2010, with Eddie Dean), Judy Collins (Sweet Judy Blue Eyes, 2011) or Robbie Robertson (Testimony, 2016) are often such toe-curling exercises: unlike many of his colleagues, Keith does have self-mockery and the ability to put things into perspective.

The (auto-)biography of Carl Perkins lacks that, self-mockery and sense of perspective. With all its unpleasant consequences: superficial, self-cleansing self-reflection, unreliable anecdotes and embarrassing self-congratulation. Perkins’ account of his meeting with Dylan in January 1992 is a case in point. Perkins tells us that he is in New York, at the Plaza Hotel, and that Bob Dylan calls up to his room from the lobby. When Dylan enters his hotel room a few minutes later, Carl barely recognises him. Dylan is “fat”, and: “looked like seventy years old with his old beard and matted hair, cap on his head”. Perkins’ description of the ensuing greeting scene is weirdly alienating:

“He said, ‘Uh-uh. We’re brothers.’ And he hugged me. And I thought he wasn’t gonna turn me loose. His beard was scratchin’ my damn face – I’d just shaved. And he’s sayin’ in my ear, I love you, man. Oh, how I love you. I love you, Carl.’ And had tears in his eyes. ‘Let me look at you.’ And he just stood there. Said, I’m so thankful. You lived through it.”

Dylan also has a present for Carl, “a small gold pin in the shape of a guitar”, and hands it over with a seemingly rehearsed, monumentally trite talk:

“There’s three thoughts that go with that little guitar,” Dylan said. “One is for gettin’ well. Two is for gettin’ up and gettin’ back out. And number three is so the world can keep lovin’ Carl Perkins alive.”

… which Perkins thinks is deeply moving and he perceives it as “so poetic”. He promises to cherish the pin and even take it to his grave (in between they hug again, for the third time now), and Dylan is just as moved: “A man can’t ask for more than that,” he declares, according to Carl. And with that, Dylan leaves the room and Perkins’ life;

“Door shut,” Carl recalls. “The little bent-over fat man with the Army coat on and ragged guitar case faded into the streets of New York, and nobody knew who he was.”

“Built a little too close to the water,” as the Germans so aptly put it in relation to übersentimental, self-affected characters, men who are moved to tears by their own goodness.

It is all so out of character and implausible that it becomes almost comical. But then again, we are talking Carl Perkins, one of the Very Greats, one of the Patriarchs, an architect, a frontman and an eyewitness from the very beginning. So his memories, his opinions and his comments are music historically important, do matter one way or another. And: for the book, co-author David McGee conducted interviews with those involved – including Dylan, in 1994. The reason being, of course, the unique, one-off collaboration between Perkins and Dylan in 1969, the co-production of “Champaign, Illinois”, the little ditty that Carl would record shortly afterwards for his nice comeback album On Top.

Thanks to McGee’s research, we get a story about the song’s genesis. Perkins and Dylan meet during the television taping of a Johnny Cash special, so that must have been May 1, 1969. According to legend, Perkins then visits Dylan in his dressing room, where, again according to Carl, Dylan explains to him that he is not getting anywhere with a new song of his. He is stuck. And he sings out, “over a ragged rockabilly rhythm”:

I got a woman in Morocco I got a woman over in Spain But the girl I love That stole my heart She lives up in Champaign I said Champaign, Champaign, Illinois

… a first verse that remains largely unchanged. Only lines 2 and 3 change to Woman that’s done stole my heart, and the chorus line I certainly do enjoy Champaign, Illinois is missing. This seems unlikely, well: half true. Perhaps due to erroneous recall by the then 61-year-old Perkins (this recollection comes from an interview conducted by McGee in 1993). In any case, it is unlikely that Dylan has already added “Illinois” without having a rhyme word. But apart from this minor issue, Perkins’s account seems credible. Indeed, this is the only part of the lyrics that still has a somewhat dylanesque touch (mainly because of the completely unusual rhyme Spain / Champaign, of course). The rest of the lyrics are rather run-of-the-mill, so probably written by a poetically less gifted lyricist like Carl Perkins. Like the second verse:

The first time that I went there They treated me so fine Man alive, I'm telling you I thought the whole darn town was mine

… in which alone the folksy darn already suggests that this was not written by Dylan.

Less credible again is Perkins’ further staging of the dressing room scene. Allegedly, Dylan plays this first, incomplete verse plus half chorus line, and asks Perkins, apparently unsure, “You think it’s any good?” And Perkins, He saw that it was good. He takes over Dylan’s guitar and easily dashes off the rest of the song:

Dylan sat transfixed as Carl worked out a loping rhythm on the bass strings with his thumb, filled in with some quick, stinging runs on the treble strings, and improvised a verse-ending lyric:

I certainly do enjoy Cha-a-am-pai hane, Illinois

Dylan said: “Your song. Take it. Finish it.”

We weren’t there, of course, but: “transfixed”? Really? All right, it’s a nice song, but no more (well, less, actually). “Transfixed” is, again, very, very out of character. This is May 1969. Dylan already has been seeing quite a bit, this decade. He has worked with master guitarists like Michael Bloomfield and top musicians like Charlie McCoy, he was on stage with Johnny Cash just an hour ago, The Beatles and The Stones are courting him, he is jamming with George Harrison and Eric Clapton, and he has been around the world a few times… With all love and respect to Carl Perkins, Dylan is no longer a rookie who freezes like a rabbit in the headlights when Carl Perkins shakes a few common licks over an ordinary chord progression out of his guitar.

It’s hardly “Blue Suede Shoes”, after all.

To be continued. Next up Champaign, Illinois part 3: So that’s where the song is going

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

Perkins say:

She lives up in Champaign

I’m well dressed, waiting for the last train

To Champaign, Illinois

Bob say that rhyme’s a way too Mundane ….

I’ll use it when I get there

champaign = flat country

champagne = sparkling wine