by Jochen Markhorst

I There’s A Tear In My Beer

Arguably one of the prettiest, though one of the most middle-of-the-road songs on Nashville Skyline is “One More Night”. And arguably the song with the most remarkable vocals, too. Even among all those other songs sung with that remarkable new voice. “Everybody remarks on the change of your singing style,” says Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner in the interview, June 1969.

Arguably one of the prettiest, though one of the most middle-of-the-road songs on Nashville Skyline is “One More Night”. And arguably the song with the most remarkable vocals, too. Even among all those other songs sung with that remarkable new voice. “Everybody remarks on the change of your singing style,” says Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner in the interview, June 1969.

“Well, Jann, I’ll tell you something. There’s not too much of a change in my singing style, but I’ll tell you something which is true… I stopped smoking. When I stopped smoking my voice changed… So drastically, I couldn’t believe it myself. That’s true. I tell you, you stop smoking those cigarettes [laughter]… and you’ll be able to sing like Caruso.”

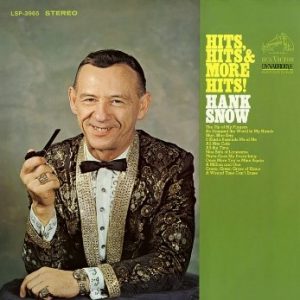

Which, of course, is total bullshit. Dylan is in Nashville, recording a country album with country musicians, has written country songs and is looking for a country voice. Hank Williams’ quiver and yodel soon sound too artificial, tenor Caruso’s high D and depth are obviously a bridge too far, but in the vast prairie between those two extremes are plenty of light, velvety baritone voices that Dylan can come close to. Hank Snow, in particular – a country hero who has been under his skin since puberty anyway.

“I’d always listened to Hank Snow,” Dylan says to Sam Shepard (True Dylan, 1986), and it’s demonstrably true. In the Basement, the men play “I Don’t Hurt Anymore”; on Down In The Groove, Dylan covers “Ninety Miles An Hour”; in the 1970s, he records, “A Fool Such As I”; in 1985, he names Snow’s “Lady’s Man” first in a list of “a dozen influential records”; and as a DJ in the twenty-first century, he plays The Singing Ranger three times on Theme Time Radio Hour, each time admiring both Hank’s repertoire (“seven numbers one, all conspicuous and distinct, plain and straightforward”) and his voice (“he was one of the biggest voices in country music”). In short: in every decade of Dylan’s career, Hank Snow passes by. Before that even; “When I was growing up, I had a record called Hank Snow Sings Jimmie Rodgers,” he says in a 1997 phone interview with Nick Krewen on the occasion of The Songs of Jimmie Rodgers – A Tribute, a star-studded tribute album organized by Dylan in celebration of Jimmie Rodgers’ 100th birthday.

“One More Night” is musically in the vein of “I’m Moving On” or “Music Making Mama From Tennessee” or “I Wonder Where You Are Tonight” anyway, one of those mid-tempo songs from that endless string (85 titles!) of Hank Snow singles from the first half of the 50s. With an intro that seems to have inspired Neil Young’s “Heart Of Gold”, by the way (the song of which Dylan says: “There I am, but it’s not me”).

Strangely, Snow’s sharper singing voice is closer to Dylan’s voice on John Wesley Harding than to the more nasal onset on Nashville Skyline, but still it does seem as if the smooth baritone of The Singing Ranger is haunting Dylan’s mind here. That’s not the most remarkable thing, though. What is particularly striking is Dylan’s largely unemotional delivery. In all the other songs on Nashville Skyline, we hear Hank Snow-like devices to communicate emotion. The near cracking in “To Be Alone With You”, the descent into a sultry baritone in “Lay Lady Lay”, the light vibrato and the hint of a head voice in “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You” and “I Threw It All Away”… the “usual” crooning tricks, as it were. But “One More Night” gets a detached, almost mechanical treatment. The opening lines,

One more night, the stars are in sight But tonight I’m as lonesome as can be

… are, admittedly, not too inspiring, but then again, so are plenty of verses in the other songs, which do get audible love in the delivery. Here, however, Dylan sounds like the jaded country star of old who has to sing his one sole hit from thirty years ago for the umpteenth time at an Oldies festival. An impression that in the last lines, in

Oh, I miss that woman so I didn’t mean to see her go

… is squared again; you can just hear how this washed-out country star wonders what the hell I am doing here, and is already, while indifferently singing these lines, thinking about the way back to his camper and his bed.

The song can take it, weirdly enough. It is, after all, a skilled, immaculate country song, Dylan is accompanied by skilled, excellent musicians who effortlessly layer an irresistible bounciness under Dylan’s drawl, and the familiar melody lines are strong enough to stand on their own, are not necessarily in need of polishing with frills and tinsel.

Just as clichéd, but no less appealing, are the lyrics, with tone, idiom and content of each tear-in-my-beer ballad between Hank Williams’ “Why Don’t You Love Me” (1950) and “There’s A Tear In My Beer”, the late Hank Williams’ unique duet with his son Hank Williams Jr. from 1988.

… lamentations which communicate the same suffering as

One more night, the stars are in sight But tonight I’m as lonesome as can be Oh, the moon is shinin’ bright Lighting ev’rything in sight But tonight no light will shine on me

The only distinguishing feature, as is to be expected from a Nobel Prize-winning poet, is the superior form. Dylan chooses, instinctively presumably, the form he tends to choose for his Very Big Songs, the Spanish sextet (six-line stanzas with the rhyme scheme aabccb). Concealed, as usual, by an inexplicable intervention by the layout editor, who rearranges all four stanzas into five-line stanzas. But both the rhyme scheme and Dylan’s delivery demonstrate that all four stanzas are “actually” Spanish sestets. This first verse, for example, is in fact:

One more night, the stars are in sight But tonight I’m as lonesome as can be Oh, the moon is shinin’ bright Lighting ev’rything in sight But tonight no light will shine on me

Just as the second verse “actually” is aabccb, turns out to be a Spanish sextet as well:

Oh, it’s shameful and it’s sad I lost the only pal I had I just could not be what she wanted me to be I will turn my head up high To that dark and rolling sky For tonight no light will shine on me

… revealed through an intervention in the opening line, an intervention that produces the same result in each of the stanzas: Spanish sextets, all of them.

We see it often enough, Dylan’s love for this form, the rather rare form of songs like “A Boy Named Sue” and “Hallelujah”. Dylan chooses it in exceptional songs like “Love Minus Zero” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, always concealing the form in the official publications (Lyrics and on the site), as here again, by re-formatting the lyrics.

It remains a mystery why Dylan, or the layout editor, would choose to do that. But it’s certainly not middle of the road, in any case.

To be continued. Next up One More Night part 2: I believe in Hank Williams

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

The band I was in back in the 90s covered “One More Night”. We did it kinda fast. It clocks in at a breezy 1:56. I’ve always loved this little song. To me, it seems like he was attempting to write a classic-sounding, almost generic Country song. And he succeeded.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sC7ULvPs1VU