Crossing The Rubicon (2020) part 1

by Jochen Markhorst

I A hard-living, hard-drinking, hard-fighting guy

Dylan provides sparingly, but with some regularity, insight into his working methods, into how he arrives at his songs. In the interview with Douglas Brinkley (New York Times, 12 June 2020) he confirms what we have known for sixty years: “The last few verses came first. So that’s where the song was going all along. Obviously, the catalyst for the song is the title line,” thus confirming the notion that Dylan often works towards a pre-cooked catchy title line.

Dylan provides sparingly, but with some regularity, insight into his working methods, into how he arrives at his songs. In the interview with Douglas Brinkley (New York Times, 12 June 2020) he confirms what we have known for sixty years: “The last few verses came first. So that’s where the song was going all along. Obviously, the catalyst for the song is the title line,” thus confirming the notion that Dylan often works towards a pre-cooked catchy title line.

We recognise that from songs like “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, “Tangled Up In Blue”, “Every Grain Of Sand”, “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven” and dozens of other songs besides “I Contain Multitudes”, the song Dylan refers to in this particular interview (adding: “Most of my recent songs are like that”).

Thanks to Daniel Lanois, we know that Dylan doesn’t necessarily already have accompanying music in his head; for the sessions of Oh Mercy, for example, Dylan arrives with written-out lyrics for songs like “Most Of The Time”, without even a hint of a melody; a melody is sought and found on the spot, in the studio.

We owe it to drummer David Kemper to learn that a single drum pattern can be enough to spark off a whole song; when Kemper is alone in the studio trying to play a rhythm he “heard somewhere”, Dylan orders him, while grabbing his notebook, to keep playing. Dylan sits down next to the drumming Kemper and in “maybe ten minutes” comes up with the whole of “Cold Irons Bound”, after which it is immediately recorded. Similarly to how Leon Russell describes the creation of “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece”: when Dylan arrives in the studio, Russell and his mates have already, without any input from Dylan, come up with and recorded a musical accompaniment, and Dylan then, while the tape is played on repeat, writes the lyrics on the spot.

And a third working method Dylan reveals, remarkably clearly and unequivocally, to interviewer Robert Hilburn in 2003 for his “Songwriters Series” in the Los Angeles Times:

“What happens is, I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head. That’s the way I meditate. […] I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s Tumbling Tumbleweeds, for instance, in my head constantly — while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.”

Since 1997, from Time Out Of Mind onwards, this seems to become a guiding principle, as well as a double-edged sword. Dylan uses “reference records”, usually old blues records by men like Charley Patton, but also by crooners like Al Jolson, to make clear to his collaborators what sound he is looking for. But apart from that sound, he also uses the licks or drum patterns, or melody lines that his musicians play along with on those “reference records” – and sometimes even licks and drum patterns and melody lines.

“Sugar Baby” (“Love And Theft”, 2001) is a replica of Gene Austin’s “The Lonesome Road” from 1927, “Floater” (also lovingly stolen in 2001) is a faithful copy of Bing Crosby’s “Snuggled On Your Shoulder (Cuddled In Your Arms)” from 1932, and the “reference record” for Time Out Of Mind‘s “‘Til I Fell In Love With You” seems to be a forgotten B-side by Slim Harpo from 1958, “Strange Love”.

More than twenty years later, when Dylan starts Rough And Rowdy Ways, this method still proves to be fruitful. One of the reference records is quite easy to trace: “Can’t Hold Out Much Longer”, the B-side of Little Walters’ first single for Checker Records, “Juke” (1952), a no.1 hit on the R&B charts. At least, its introductory lick gets to be the “start-lick”, the departure point of every verse of Dylan’s “Crossing The Rubicon”.

https://youtu.be/cuyO8ClCxeQ?list=RDcuyO8ClCxeQ

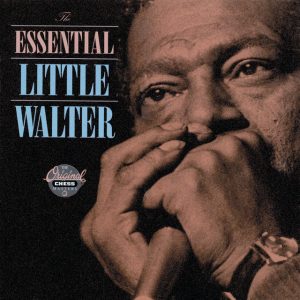

And beyond that, Little Walter hovers just as recognisably over the song; the stomp, the sound and the Chicago influence of slow blues like “Key To The Highway”, “Last Night” and “Little Girl” set the tone for Dylan’s song. All songs which can be found on The Essential Little Walter, a double CD from 1993 that indeed collects the highlights of Little Walter’s recordings for Chess Records (1952-1965). Also including the five songs that DJ Dylan plays in his Theme Time Radio Hour, always accompanied by roaring admiration for Walter’s skill and musical talent. Like at the evergreen “Key To The Highway” in episode 66, Lock & Key;

“This next song has a lot of different versions. Just about all of them are good. You can hear it by Count Basie, you can hear it by Eric Clapton, hear it by Buddy Guy. John Hammond Jr., the Derek Trucks Band, Junior Wells or The Band. I’m not gonna play it by the guy who wrote it either. I’m gonna play the version that I like – the best version. Here’s Little Walter, singing Big Bill Broonzy’s “Key To The Highway”.”

The DJ is serious. Twelve years later, when Dylan records “Murder Most Foul”, he reaffirms his admiration: “Play ‘Moonlight Sonata’ in F-sharp / And the ‘Key to the Highway’ for the king on the harp”, the honorary title of master harmonica player Little Walter.

The songs on The Essential Little Walter even leave traces in the song’s content, by the way; a verse fragment like this world so badly bent is most likely an echo of the last song on Disc 2, “Dead Presidents” (Well I ain’t broke but I’m badly bent) – a song that is also on the DJ’s playlist (episode 68, Presidents’ Day).

But the “Bob Nolan” method, as we will call it for now, seems to have led to “Crossing The Rubicon”. Dylan listens to the song in his head, and “at a certain point, some of the words change.” Speculation, of course, but the opening words of the final couplet are good candidates for such an inner, creative process – the most obvious seems to be the option that Dylan changes the words of Little Walters’ refrain You know I’m just crazy about you, baby / Wonder, do you ever think of me, while humming, into

Mona, baby, are you still in my mind? I truly believe that you are

… and then the floodgates to the wildly swirling stream-of-consciousness open. This scenario would imply that Dylan moves these “opening words” to the end of the song after his work is done, and that is not unusual. We know, both from Dylan’s notebooks and from statements in interviews, that the bard often shuffles verses back and forth, to “have the cycle of events working in a rather reverse order,” as Dylan explained it to John Cohen half a century before (Sing Out!, October 1968), when a relatively young Dylan still thinks that is an original narrative structure.

And who knows, maybe biographical associations with Little Walter do flood in first. Little Walter, as DJ Dylan repeatedly points out, was not only an extremely talented and skilful musician but also a difficult man. “Walter was a hard-living, hard-drinking, hard-fighting guy,” says a poetically inclined DJ when he plays Little Walter for the first time (23 August 2006), and he repeats words to this effect on subsequent spins in later episodes. Muddy Waters’ description is even more poetic: “Little Walter was dead ten years before he died,” referring to Walter’s worn-out appearance and alcoholism, and his look, the old-before-his-time look. Which Dylan also notices;

“He died at an early age, 38 years old. But if you see pictures, he looks closer to sixty. A hard-living man, but a great artist.”

The last time the radio maker plays a record by Little Walter (episode 90, Madness, 4 February 2009), Dylan is a little less shrouded:

“Sadly, Walter had a vicious temper and a thirst for liquor. He was involved in a street fight and died from its after-effects. He was only 37 years old.”

The best biography on Little Walter was written by Dylan’s old comrade Tony Glover (Blues With a Feeling: The Little Walter Story, 2002), and it is quite likely that Dylan has read that book – or at least used it as a reference. And that Dylan has also read that the fatal street fight, the fight after which Walter crosses the Rubicon, takes place in Chicago, on the 14th day of the most dangerous month, 14 February 1968.

To be continued. Next up Crossing The Rubicon part 2: That day I’ll always remember

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

———————

Untold Dylan also has its own Facebook page with over 11,000 followers. To find us just type in Untold Dylan Facebook and the relevant page ought to pop up.

Bob Nolan as a child lived up the St, John River not far from here at Hatfield Point, New Brunswick.

Hank Snow as a child, across the Bay of Fundy, in Brooklyn

Noval Scotia.

Needless to say, Bob Dylan would be a complete unknown were he not standing on the mighty shoulders of these two Maritime giants.

Rumour has it that Robert Zimmerman was originally going to call himself

“Bob Snolan”.

Don’t get smart with me young feller …

It’s Maritimers all the way down ~

But with the dawn

I’ll wake up and yawn

(Bob Nolan: Cool Water)

To wit:

I got up early

So I can greet the goddess of the dawn …

And I crossed the Rubicon

(Bob Dylan: I Crossed The Rubicon)

All the way down ~

Down at the pawnshop, down at the pawnshop

They got my watch and everything

(Hank Snow: Down At The Pawnshop ~ Don Deal)

To wit:

I pawned my watch, I paid my debts

And I crossed the Rubicon

(Bob Dylan: I Crossed the Rubicon)

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/4922/Crossing-The-Rubicon

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.