by Jochen Markhorst

No comments are known from Dylan about the uncrowned king of underground comics, Robert Crumb. And comments vice versa are not too flattering: “When Joan Baez and Bob Dylan and all that folknik stuff came out, I just found it irritating. Hated it. It sounded silly to me. Dylan was trying to be “raw” but not convincing.” (Record Collector Magazine, 15 July 2015).

No comments are known from Dylan about the uncrowned king of underground comics, Robert Crumb. And comments vice versa are not too flattering: “When Joan Baez and Bob Dylan and all that folknik stuff came out, I just found it irritating. Hated it. It sounded silly to me. Dylan was trying to be “raw” but not convincing.” (Record Collector Magazine, 15 July 2015).

Nonetheless, it’s fairly certain that both icons could have an enjoyable evening together at a table in a juke joint, with enough quarters for the jukebox. After all, there is a huge patch of common ground: the deep, deep love of real, authentic rural music, as Crumb calls it, the old stuff and crazy hillbilly Okie singers and the rugged blues of the 1920s and 1930s, “conjuring up visions of dirt roads and going deep into the back country.” Words after Dylan’s heart, of course.

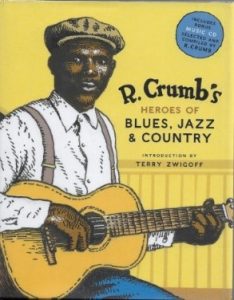

Just as close to Dylan’s heart is the collection R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz & Country, 21 songs compiled by Crumb in 2006. Seven songs by Pioneers Of Country Music like Dock Boggs (“Sugar Baby”) and Hayes Shepherd (“The Peddler And His Wife”), seven Early Jazz Greats like Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra and Jerry Roll Morton, and seven Heroes Of Blues all idolised by Dylan: the Memphis Jug Band (with “On The Road Again”, the song to which Dylan dedicates an essay in his Philosophy Of Modern Song), Blind Willie McTell (“Dark Night Blues”), Charley Patton (with “High Water Everywhere”) and Skip James’s “Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues”, among others.

Next to a jukebox filled with Crumb’s selection, the men would, in short, undoubtedly forge a deep soul connection. And, who knows, if the tête-à-tête takes place in the twenty-first century, Crumb might even tolerate a single Dylan song in the jukebox. “Dirt Road Blues” perhaps, or “Crossing The Rubicon”, one of those songs harking back to older blues. Although for the versatile bandleader of the Cheap Suit Serenaders, that is also presumably still too inauthentic; even recognised greats like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters are to him “electric stuff, wanting to be seen as sophisticated, to embrace the prevailing urbanity.” And anyway, he is not a fan of jukeboxes either, for that matter: “By 1939 there were 400,000 jukeboxes! That immediately eliminates so many live musicians – a juke joint, which is where jukeboxes got their name from – would fire the barrelhouse pianist.”

No, for all the sympathy Fritz the Cat’s father will feel for the intentions of, say, “High Water (For Charley Patton)” or “Red River Shore”, he will dismiss those masterpieces too for being “sophisticated”, as inauthentic. Not to mention the songs Dylan himself dares to call “blues”. “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, “Outlaw Blues”, “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, “Tombstone Blues”… fan favourites, but also songs that embrace the prevailing urbanity. On which, by the way, Dylan himself may also have a more nuanced opinion in his later years;

“To me, the blues are a more rural, agrarian type of thing. And even when they’re taken to the big city, they still remain that way only pumped up with electricity. That’s the thing: I mean, we’re listening to all this music today, it’s all electricity. Electric guitars, electric bass, electric synthesizers – it’s all electronic. You don’t really feel somebody breathing, you don’t feel their heart in it. The further away you get into that, the less you’re going to be connected to the blues. The blues to me is just a pure form, like old country music.”

(London Press Conference, 4 October 1997)

Crumb will nod in agreement. And then somewhat sardonically inquire how Dylan would then categorise his own “Living The Blues”.

“Irony,” Dylan might reply. After all, there is a certain incongruity between words like

Since you’ve been gone I’ve been walking around With my head bowed down to my shoes I’ve been living the blues Ev’ry night without you

… and the neatly coiffed, blue-eyed, conservatively dressed good family man singing these words soothingly, standing in the glamorous setting of The Johnny Cash Show.

In fact, exactly what he had an opinion about seven years ago, in the liner notes of The Freewheelin’:

“What’s depressing today is that many young singers are trying to get inside the blues, forgetting that those older singers used them to get outside their troubles.”

Still, it is a charming song. But miles away from what both the elder Dylan and Robert Crumb associate with “blues”. That, of course, already applies to the song’s template, the time-honoured “Singing The Blues”, which also really should have been called “Singing A Schlager”, and, like Dylan’s dilution, is mostly sophisticated, polished and artificial – up to a point, authenticity really does co-determine the art pleasure.

Crumb sets the example both in the selection of his compilation album and in images; the bonus to Crumb’s wonderful tribute R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz & Country is a collection of drawn portraits of the heroes, colourful trading cards, like baseball cards, with the heads of Son House, Blind Willie Johnson, Leroy Carr and all those others, everyone drawn with the love and respect of a devout fan.

But the most love and beauty Crumb puts into the graphically stunning comics that tell the life stories of his blues heroes in black and white, compiled in R. Crumb Draws the Blues. Also containing one of Crumb’s absolute masterpieces, “Patton”, the life story of Charley Patton, which oppressively and overwhelmingly depicts what living the blues really is like – from the struggle to follow your calling, the violent and fatal love adventures, the pub fights, the madness, the flood catastrophe, the wandering on the deserted dirt roads to the death that slowly creeps into first Patton’s life and then his songs and finally, three days before his 43rd birthday, fells him. Patton’s fatal lover Bertha Lee sits at his deathbed; otherwise, his passing goes unnoticed.

With Dylan’s lyrics, then, Crumb will have some peace. At least, there is little offence in it for a man who longs for “that sound of something old and atavistic” – after all, “Living The Blues” is entirely free of sophistication; three unimaginative, clichéd couplets with easy-going rhymes like I don’t have to go far / To know where you are and a bridge with all the poetic depth of, say, Roscoe Holcomb’s white hillbilly music, of Crumb’s beloved “authentic rural music”. Still, as far as the rest goes… No, though Crumb, generally speaking, is particularly modest and reticent about his own music recordings, in this case he had probably stood up, stopped “Living The Blues”, and put on something from his own Cheap Suit Serenaders. “Crying My Blues Away” (Chasin’ Rainbows, 1993) presumably;

I sit around and twiddle my thumbs make not a sound and nobody comes with my head hanging low I’m crying my blues away.

And it is quite likely that the Dylan of the twenty-first century would then have slid a quarter across the table. “Play it again, Robert.”

—————————-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

I can’t remember the last time I used my priviledged position of being the first person to read a piece by Jochen, (taking his script and setting it in the blog), to comment upon, let alone criticise, something in one of his articles.

But there’s a little, tiny, probably insignificant detail that the musician in me wants to correct.

The notion that “Living The Blues” is entirely free of sophistication, is not quite right, because in the middle 8 (the variant section which Jochen quite correctly calls the “bridge” but some of us old timers still call the “middle 8”) is musically unlike anything I’ve heard done in a standard “A B A” song. That sequence (for the lyrics “I think that it’s best” goes

F….

F….

C G C

D…

D…

G F Dm Em Am F

In fact so unexpected is that, I had to go back to the master (Eyolf Østrem) to check I was hearing it properly. And for once it seems that age and tinnitus has not betrayed me. Other songs modulate, but this song goes from C to G in a way that I don’t know another song does. In fact I can’t think of any other song using that final chord sequence, at least not as part of the “middle 8”.

Jochen, I know it’s a tiny point only of interest to passing musicians, but well, as I sit here pondering the English countryside, sometimes I just can’t help myself.

We who are have the right to use the double royal ‘t”s and ‘f”s in our last names, should note the photo of Johnny Cash with Prince Charles in Fredericton NB.