by Jochen Markhorst

VI Some stupid with a flare gun

There’s smoke on the water, it’s been there since June Tree trunks uprooted, ’neath the high crescent moon Feel the pulse and vibration and the rumbling force Somebody is out there beating on a dead horse She never said nothing, there was nothing she wrote She went with the man In the long black coat

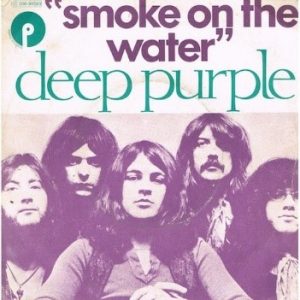

By now it has obtained the status of an urban legend, but it really is true, factually accurate historiography; the story behind Deep Purple’s “Smoke On The Water”.

By now it has obtained the status of an urban legend, but it really is true, factually accurate historiography; the story behind Deep Purple’s “Smoke On The Water”.

On 4 December 1971, the hairy hard rockers really are in Switzerland, on Lake Geneva, to record the album Machine Head at the Montreux Casino.

And indeed have to find another venue…

We all came out to Montreux on the Lake Geneva shoreline To make records with a mobile, yeah We didn't have much time now Frank Zappa and the Mothers were at the best place around But some stupid with a flare gun burned the place to the ground Smoke on the water, a fire in the sky

… yes, because some stupid Zappa fan fires a flare gun during the Zappa concert, after which the entire complex burns down. Clouds of smoke drift across the lake, flames shoot into the air, and bassist Roger Glover has his chorus (vocalist Ian Gillan writes most of the remaining, rather awkward, lyrics, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore is the architect of the monumental, immortal riff).

Dylan opens the last verse of his 1989 “Man In The Long Black Coat” with There’s smoke on the water, and a scenario in which it escapes him that he is quoting Deep Purple is extremely unlikely. For half the world’s population, hearing those words immediately rumbles in Blackmore’s riff, and Dylan certainly belongs to that half of the world’s population.

While there is a – theoretical – possibility that Dylan wants to give a nod to his old country hero Bob Wills, who had a No. 1 hit with Red Foley’s “Smoke On The Water” in 1945, that is not too likely. Pleasant tune, sure enough, with toe-curlingly naive, patriotic lyrics (if possible, even worse than Deep Purple’s “Smoke On The Water”), but apart from that: Dylan is most certainly aware of the fact that the associations of everyone of his listeners are pushed towards the hard rock classic, not towards a country hit from half a century ago.

Moreover, a few years later Dylan also paraphrases the second half of Deep Purple’s refrain line, fire in the sky, in “Mississippi” (sky full of fire, pain pouring down) – for some reason Roger Glover’s words do roll into Dylan’s stream-of-consciousness every now and then.

Anyway, much more than a casual nod to an untouchable monument Dylan’s choice of the words smoke on the water really can’t be; there is no further indication that he has a soft spot for the band. Deep Purple is never mentioned, not in interviews or otherwise. Yes, one single time, via a diversion, in Theme Time Radio Hour, when DJ Dylan plays The Ravens’ evergreen “Deep Purple” (episode 47, Colors, aired February 28, 2007): “And no, I’m not talking about the one-time holders of the Guinness World Record for being The Loudest Band In The World.”

Conversely, the men talk about Dylan often enough, by the way. Ritchie Blackmore is an outspoken fan, for instance. “He is the only person I admire in the business,” he says, “I have been in the business for so long, he’s the one that I still feel he remains mysterious, there is something about him that I think is truly monumental and he is so creative.”

Roger Glover tells interviewer Mark Dean (Antihero Magazine) in 2017 that Dylan is “my all-time favourite songwriter”, and adds, to the interviewer’s surprise, “but I’ve got this kind of strange feeling that I don’t want to meet him.” Because he has such a difficult reputation surely, Dean suspects. No, not at all, Glover explains:

“Well, it’s not so much that. It’s that he is what he is, in my mind, and I don’t want that to change, because he’s so precious. I don’t want to know that he’s just a guy. I know he is. Do you know what I mean? I think the kind of questions I’d want to ask him, he’d be pretty bored with, anyway.”

… a motivation remarkably similar to Dylan’s explanation of why he passed up the chance to meet Elvis back then – Dylan, too, preferred to keep the myth alive. But meanwhile, we thus miss the chance of Roger Glover, someone with the right to speak, finally asking Dylan a “pretty boring” question like why he sings those words smoke on the water in “The Man In The Long Black Coat”.

Years later, when Dylan has inserted in the preceding bridge the new line I went down to the river, but I just missed the boat, he seems to lift a small corner of the veil. If Dylan was initially inspired by “House Carpenter”, and indeed set up his song as a kind of answer song, a song in which the abandoned spouse from “House Carpenter” gets the stage, then with that smoke on the water we suddenly have a symbolic set detail that fits the narrative just fine. After all, the frivolous wife who runs off with the Devil (or Death, or a ghost) in “House Carpenter” leaves by boat. And then perishes with him;

Oh twice around went the gallant ship I'm sure it was not three When the ship all of a sudden, it sprung a leak And it drifted to the bottom of the sea

… and from the shore the abandoned husband sees, or we see, then only smoke on the surface of the water, below which the pulse and vibration and the rumbling force are audible and discernible. Fitting, then, is the second notable lyric change: in the first decade of the twenty-first century, Dylan changes the second line, “’neath the high crescent moon” to “there’s blood on the moon”.

Semi-officially, by the way: in the official 2004 edition of the lyrics, Lyrics 1962-2001, the crescent moon is changed to this bloody moon, but in the next edition (Lyrics 1961-2012 from 2014) and on the site the original lyrics from the studio recording have been restored, returning to ‘neath the high crescent moon – as Dylan sings it on stage again after 2009, by the way.

The other lyrics change, I went down to the river, but I just missed the boat, is retained. As is some stupid who’s beating on a dead horse…

To be continued. Next up Man In The Long Black Coat part 7: Somebody is out there feeding a fed horse

——-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

Starting off with modern references to the Deep Purple club-burning song,

and patriotic Wills song for lines used by Dylan underplays the earlier biblical roots that both these songs have:

And I will shew wonders in heaven above

And in the earth beneath

Blood, and fire,and vapour of smoke

The sun will be turned into darkness

And the moon into blood

Before the great and notable day of the Lord come

(Acts 2: 19,20)

Saint Paul could be the man in the long black coat; he considers the end times to be coming very soon while a number of Dylan songs burlesque the fact that the Second Coming is taking far too long to arrive – ie, the beating of the dead horse and the missing of the boat – which could explain the reason why the line about blood on the moon gets removed, and replaced by the crescent moon which suggests a regenerative Horus/Isis-like cycle.

Said it could be that the woman represents the Bride of Christ (the Christian Church), and that she takes off with fire and brimestone preacher Paul.

So it can be said that in ‘Spirit On the Water’ the Jewish narrator therein would like to have a good time in the dance hall with Christian companions but alas too many believe (like St. John) that he’s responsible for killing a man back there – that man being Christ.

Related too is “Sign On The Cross”

From the same poetic cup pours the motifs of the wandering Jew; the stranger in a strange land; and the drifter who escapes from his oppressors.

Engels had much to do with inserting the “religious” analogy that the working class has no home of its own in Marx’s materialist conception of history that leads to the establishment of capitalist mode of production.

That is, so-called “human nature” has little to do with the workers’ position therein ~ the ownership of the means of production is what counts.

Romantic-inclined Dylan, or at least his artisic persona, criticizes the Babylonian-like worship of the ‘golden calf’, but Marx’s ”axe” as far as the artist is concerned be no match for the strength of the spiritual shield that protects “human nature” from seeking any radical long-term change in the material human condition.