by Jochen Markhorst

I He was a real magpie

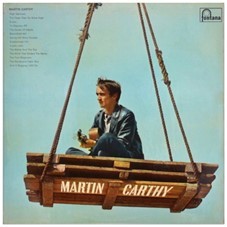

The sympathetic English folk giant Martin Carthy has an admirable talent for getting to the point with perfect metaphors. As to characterise an exceptional quality of young Dylan:

The sympathetic English folk giant Martin Carthy has an admirable talent for getting to the point with perfect metaphors. As to characterise an exceptional quality of young Dylan:

“He was a real magpie, but he had this wonderful creativity that went along with it. […] What he had was a memory like a piece of blotting paper. If somebody sang something that he thought was wonderful, he’d go back to his hotel and write down what he remembered. It might come out as a new song, but that’s where it would be from.”

(Tradfolk interview, 28 February 2018)

“He was a real magpie” is a wonderful, comprehensive image. Typifying not only the young troubadour with whom Carthy roams London from one folk club to another, but actually the old one as well. The magpie who picks up the shiny bits and takes them to his nest to build his own work of art. And Carthy illustrates his memories with familiar and less familiar examples. I heard him, he tells us, singing “Where have you been my blue-eyed son?”, and thought he was playing “Lord Randall” – until three seconds later I realised it was “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”.

Dylan’s incredible memory for songs, as well as his lovingly copy/paste talent, has of course been spotted often enough as well, but rarely as evocatively as by Carthy: “What he had was a memory like a piece of blotting paper.” And reconstructing those memories, those quickly stored impressions, back in his hotel room, then become the basis for what “might come out as a new song”. In which he exposes a creative process, as it is described by the 62-year-old Dylan himself too, in the Robert Hilburn interview for the LA Times, November 2003 in Amsterdam:

“I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds,’ for instance, in my head constantly — while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.”

Incidentally, it is hard to find a song in Dylan’s oeuvre that features a “changed” “Tumbling Tumbleweeds”. “Rollin’ And Tumblin'” seems obvious, but doesn’t fit – in terms of atmosphere and pace, songs like “Life Is Hard” or “Moonlight” come closer, but presumably Dylan just mentions a song that comes to mind at this moment, during this interview.

However, there are plenty of songs in Dylan’s oeuvre where it is abundantly clear what the template is, of course. The old Irish drinking song “The Parting Glass” for “Restless Farewell”, for example, “Nottamun Town” becomes “Masters Of War”, or “No More Auction Block” for “Blowin’ In The Wind”; there are dozens of examples. And one of the most famous and celebrated is “Scarborough Fair”, from which Dylan sculpted one of his all-time greatest, “Girl From The Country”. According to lore, anyway.

“Scarborough Fair” was “my thing”, says Carthy. Every artist in that folk circle, in the late 50s, early 60s, had their own “signature song”, so to speak. Davey Graham had “Angi” (or “Anji” or “Angie”), Bert Jansch “Strolling Down The Highway” and Carthy had “Scarborough Fair”. He stopped playing it himself (“too much baggage”), but “I love the fact that Bob Dylan got ‘Girl From the North Country’ from it. It was very typical of him to do that – very him. In fact, he came back and he said [cue Bob Dylan impersonation], “I wanna sing you this!” And he started to sing it, and he was trying to do the guitar figure. He got halfway through the first verse and he said, “Oh man, I can’t do this!” [Laughs] He wasn’t really ready. He was just so excited about it.”

… and that “Scarborough Fair” was more or less taken away from him by Paul Simon doesn’t really bother him anymore either: “It was my signature piece, but it’s a traditional song, for god’s sake! Why shouldn’t he do it?” When Paul Simon performs in London in 1998, he apparently remembers a debt of honour, and invites Martin on stage to play the song together. The generous Carthy is happy to oblige.

Like Simon, Dylan is still aware of Carthy’s contribution decades after the fact, as evidenced by his words in the Rolling Stone interview in 1984:

“But I ran into some people in England who really knew those songs. Martin Carthy, another guy named Nigel Davenport. Martin Carthy’s incredible. I learned a lot of stuff from Martin. ‘Girl From The North Country’ is based on a song I heard him sing – that Scarborough Fair song, which Paul Simon, I guess, just took the whole thing.”

Which, by the way, contradicts his own quote in Nat Hentoff’s liner notes on The Freewheelin’. Hentoff writes there:

“Girl From The North Country was first conceived by Bob Dylan about three years before he finally wrote it down in December 1962.”

… and then quotes Dylan, who implicitly confirms this genesis: “That often happens. I carry a song in my head for a long time and then it comes bursting out.” Which is then rebutted by both Carthy and Dylan himself, and a first superficial song comparison indeed does demonstrate it; Dylan must have turned the old folk song into “Girl From The North Country” in the same days that he was introduced to Carthy’s version of “Scarborough Fair”, December ’62. That he would have walked around with it for “about three years” is one of the many fables peddled in those liner notes. And actually, the gravity of the template is somewhat overblown as well.

https://youtu.be/M32jmUmSZzU

The plot of “Scarborough Fair”, the dialogue about a love that can only be won if the other accomplishes impossible tasks (sewing a seamless cambric shirt, finding an acre of land between the salty seawater and the wet beach) evaporates, to be saved, in a way, for the equally stunningly beautiful sister of the girl from the North, for “Boots Of Spanish Leather”. A few phrases are taken verbatim – but not many; only Remember me to one who lives there / For once she was a true love of mine, in fact.

And the melody may be an echo, though not much more than that – the outline is recognisable, but the harmonic structure is really different. And so is the time signature – Scarborough is played in 6/8 or 3/4, Dylan plays an ordinary 4/4 metre. There are, in any case, plenty of songs in Dylan’s discography that are much more faithful to the template than “Girl From The North Country” is to “Scarborough Fair”. It is, in short, defensible that Dylan considers the song an own creation. Which, incidentally, Martin Carthy implicitly acknowledges when he says:

“He did actually annoy some people by being such an effective piece of blotting paper. I don’t understand that, personally. I think it’s fantastic. Somebody suggested that “Blowin’ In The Wind” was actually a reworking of a tune called “No More Auction Block”. I’ve no idea if that’s true. There’s only a limited number of notes in the scale, aren’t there? You gonna trip over each other at some point.”

(interview for Prism Films, 2013)

To be continued. Next up Girl From The North Country part 2: La Gazza Ladra

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

Wrongfully considered a Civil War Song only, “No More Auction Block” be sung by slaves who earlier fled to Canada.

Not only is the tune reworked in “Blowing In The Wind”, the sentiment expressed also:

No more driver’s lash for me

No more, no more

Many thousands gone …

No more auction block for me

To wit:

Yes, and how many years can a mountain exist

Before it is washed to the sea

Yes, and many years can some people exist

Before they are allowed to be free

* how many ..

I rolled and I tumbled

I cried the whole night long

Woke up this morning

And I must have bet my money wrong

(Bob Dylan)

Be a bit of an inversion of the sentiment expressed – by the one-time New Brunswicker – below:

I’ll keep rolling along

Deep in my heart’s a song

(Bob Nolan)