Black Rider (2020) part 1

by Jochen Markhorst

I He must keep himself clean in speech

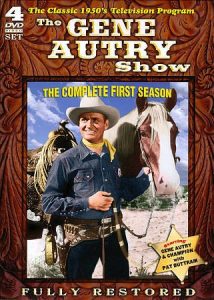

On 23 July 1950, when CBS airs the first of 91 episodes of The Gene Autry Show, Robert “Bobby” Zimmerman is nine years old – at an age, that is, that makes him extremely susceptible to the one-dimensionality, simplism and morality of “America’s Favorite Cowboy”. The episodes last half an hour, and in that half hour, Gene has an adventure, usually one in which he catches a mean crook, sings a song, and lives his insufferably righteous Cowboy Code. “The cowboy must always tell the truth”, “must help people in distress”, and “must never go back on his word, or a trust confided in him”… all ten commandments of the Cowboy Code are recited with apparent approval by DJ Dylan in 2006 in “Guns”, episode 25 of his Theme Time Radio Hour (“And I’m not ashamed to say that I live my life according to that code”).

On 23 July 1950, when CBS airs the first of 91 episodes of The Gene Autry Show, Robert “Bobby” Zimmerman is nine years old – at an age, that is, that makes him extremely susceptible to the one-dimensionality, simplism and morality of “America’s Favorite Cowboy”. The episodes last half an hour, and in that half hour, Gene has an adventure, usually one in which he catches a mean crook, sings a song, and lives his insufferably righteous Cowboy Code. “The cowboy must always tell the truth”, “must help people in distress”, and “must never go back on his word, or a trust confided in him”… all ten commandments of the Cowboy Code are recited with apparent approval by DJ Dylan in 2006 in “Guns”, episode 25 of his Theme Time Radio Hour (“And I’m not ashamed to say that I live my life according to that code”).

The 91 episodes have, even by 1950s standards, an awkwardly naive Boy Scout tone, the acting is tear-jerkingly bad, the scripts and dialogues don’t rise above the level of a primary school musical, and the humour component provided by side-kick Pat Buttram is kindergarten-level (Pat stumbles, drum rolls; it doesn’t get much more sophisticated), but: the series runs for five seasons, is a success and anchors the reputation of the already immensely popular Singing Cowboy Gene Autry – especially with impressionable nine-year-old Bobby Zimmerman.

The series is now being shown again on Amazon Prime, the DVD box sets are still selling – apart from a certain cult status, Gene Autry also has a reassuring, nostalgic quality for surviving members of the Silent Generation and for Baby Boomers like Dylan. And one of the most popular episodes seems to be: “The Black Rider” season 1, episode 14.

In terms of content, there is no overlap with Dylan’s song. The serial-killing black rider is the avenging sister (Sheila Ryan) of executed murderer Rocky Dexter, who checks off the list of men she believes are responsible for her brother’s death. This black rider is a cold-hearted sadist, who smilingly shoots law enforcement officers through the heart from close range and shows no remorse when she is eventually caught by Autry. Little common ground, in short, with Dylan’s Black Rider.

But an educated guess is that Autry has thereby inserted the timeless, irresistibly fascinating and (apart from Zorro) always sinister image of “the black rider” into Dylan’s cultural baggage. And lasting respect for Autry himself, presumably. At least, we can hear Autry traces throughout Dylan’s oeuvre from the 1960s (Autry’s “The Rheumatism Blues” seems to be the court supplier for “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”) into the twenty-first century (Dylan’s Autry cover “Here Comes Santa Claus” opens Christmas In The Heart, for instance).

After that first, crushing encounter with a Black Rider (who turns out to be a badass fatal woman in the process), the then nine-year-old Dylan, like all of us, will be confronted with dozens of Black Riders, which only carves the image deeper into our cultural baggage. We meet them in the Bible, countless Westerns, songs, tales of knights and romances of chivalry, fantasy films… though each new generation gets its own archetypal Bad Man or Evil Force, every generation gets a Black Rider. The millennials are to be envied. Their image of a Black Rider is the scariest of them all: the Nazgûl, the Ring Spirits, the Black Riders from Lord Of The Rings (in Peter Jackson’s 2001 film adaptation), responsible for an entire generation’s first experience with a blood-curdling movie scene – when Frodo and his fellow hobbits get off the path just in time and hide under a tree stump;

“The hoofs drew nearer. They had no time to find any hiding-place better than the general darkness under the trees; Sam and Pippin crouched behind a large tree-bole, while Frodo crept back a few yards towards the lane. […] The black shadow stood close to the point where they had left the path, and it swayed from side to side. Frodo thought he heard the sound of snuffling. The shadow bent to the ground, and then began to crawl towards him.”

(J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, 1954)

And as well as generationally, the archetype is transcending cross-culturally too; every nation, in all times, has at least one dark horseman in its canon. The German Kriegskindergeneration (the generation of war children) presumably thinks of John Wayne, because he made such an impression in Der schwarze Reiter (English title “Angel and the Badman”, 1947) as a notorious-gunman-who-repents, while the French contemporaries, on the other hand, will think of Le Cavalier Noir with a wistful smile, Russians see the Devil, Generation X sees Monty Python’s Black Knight looming, Spaniards might think of the Jinetes Negros, Charles V’s dreaded 16th-century elite corps, and as a nickname for smugglers, we have known Black Riders all over the world.

Dylan’s Black Rider, however, has none of these unambiguous identities – or perhaps just a little of everything indeed. The protagonist has a somewhat duplicitous relationship with this Black Rider; his dramatic monologue expresses both hatred and compassion, both admiration and disgust, and both submission and superiority. In any case, this Black Rider does not seem overly sympathetic. Nor does the protagonist, for that matter, who does not seem to live by the Cowboy Code either.

In more ways. But at the very least, in the last verse, the verse with the bizarre line The size of your cock won’t get you nowhere, he unceremoniously does violate the eighth commandment: “He must keep himself clean in thought, speech, action, and personal habits.”

https://youtu.be/6S3I4EAwtpU

To be continued. Next up Black Rider part 2: O where are you going?

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

Black rider, black rider, all dressed in black

I’m walking away, you try to make me look back

My heart is at rest, I’d like to keep it that way

I don’t wanna fight, at least not today

Go home to your wife, stop visiting mine

One of these days I’ll forget to be kind

about the time i disrespected his wife and he assaulted me

Gene Autry’s “home where the buffalo roam” echoes in Dylan’s “go where the buffalo roam” (Roll On John).

“Home On The Range” is a bit older than that, Larry.

I’m addressing the time when Autry made it famous ….

the history of the song I’ve addressed previously on Untold

I know that!, Jochen.