“So much beauty, so little time,” my grandmother used to sigh, standing in front of her record cabinet. And mind you, she only had one single Dylan record (Greatest Hits) – Rough And Rowdy Ways she did not live to hear.

“So much beauty, so little time,” my grandmother used to sigh, standing in front of her record cabinet. And mind you, she only had one single Dylan record (Greatest Hits) – Rough And Rowdy Ways she did not live to hear.

“Key West”, “My Own Version of You”, “Murder Most Foul”… the songs of Rough And Rowdy Ways are bulging treasure troves. A book on the album would become an even thicker paving stone than Mixing Up The Medicine, so I chose to just chop it up into manageable chunks. Following I Contain Multitudes (www.amazon.com/dp/B0CCCRZ257) and Crossing The Rubicon (www.amazon.com/dp/B0BFNZ4RDY) is now published: Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B. About the three songs on Side B; “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You”, “Black Rider” and “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”.

It’s an album that just keeps on giving.

—————————-

Goodbye Jimmy Reed (2020) part 8

by Jochen Markhorst

VIII What’s in my own head and what’s in my own heart

They threw everything at me, everything in the book Had nothing to fight with but a butcher’s hook They have no pity - they never lend a hand I can’t sing a song that I don’t understand Goodbye Jimmy Reed - goodbye and good luck I can’t play the record ‘cause my needle got stuck

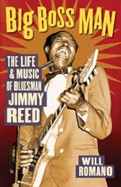

While with some tolerance you could still maintain that Dylan is building a Jimmy Reed memorial in this fourth verse too, there are more counter-arguments. They threw everything at me, everything in the book is a complaint of a narrator who has stumbled through life tripping over justice, fate and bad choices. The little we know of Jimmy Reed’s life history is not in line with that. Born on a Mississippi plantation in 1925, one of nine children of a sharecropper. Works in the fields, sings in the church choir, learns to play guitar at an early age, along with his lifelong friend and later band member Eddie Taylor. Moves to Chicago at eighteen, serves two years in the U.S. Navy during the war (1944-45, mainly in the kitchen of a barracks in California, where he learns to read and learns to drink), marries the wonderful Mary Lee “Mama” Reed, and has with her and their eight children a few years of something close to suburban bliss in Gary, Indiana. In Gary, Jimmy also briefly works in a meat-processing plant – with which more tolerant Dylan exegetes see the second line, Had nothing to fight with but a butcher’s hook, explained. Which might be a bit überenthusiastic interpreting.

While with some tolerance you could still maintain that Dylan is building a Jimmy Reed memorial in this fourth verse too, there are more counter-arguments. They threw everything at me, everything in the book is a complaint of a narrator who has stumbled through life tripping over justice, fate and bad choices. The little we know of Jimmy Reed’s life history is not in line with that. Born on a Mississippi plantation in 1925, one of nine children of a sharecropper. Works in the fields, sings in the church choir, learns to play guitar at an early age, along with his lifelong friend and later band member Eddie Taylor. Moves to Chicago at eighteen, serves two years in the U.S. Navy during the war (1944-45, mainly in the kitchen of a barracks in California, where he learns to read and learns to drink), marries the wonderful Mary Lee “Mama” Reed, and has with her and their eight children a few years of something close to suburban bliss in Gary, Indiana. In Gary, Jimmy also briefly works in a meat-processing plant – with which more tolerant Dylan exegetes see the second line, Had nothing to fight with but a butcher’s hook, explained. Which might be a bit überenthusiastic interpreting.

No less atypical is the lament They have no pity – they never lend a hand. Jimmy Reed’s career was considerably hampered by his much belatedly diagnosed epilepsy and by his devastating alcoholism, but he really could not complain about a lack of pity nor of helping hands. Without Mama Reed, who sometimes audibly stood by him (giving directions, writing songs and coaching lyrics during performances and recordings) and the support of Vee-Jay Records, we might never have heard of the man. The existential wailing doesn’t really fit Reed’s oeuvre either. In it, small sufferings predominate anyway. Adultery, no money, falling in love – the “normal” themes really, which may also explain Reed’s crossover success. The unfathomable misery of the first three lines of this fourth verse, however, rather exudes the same despondency as “Cross Road Blues”, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground”, “Hard Time Killin’ Floor Blues”, as the repertoire of the Founding Fathers, of Robert Johnson, Skip James, Blind Willie Johnson, that category.

A slightly stronger argument for the possibility that Dylan is indeed erecting a monument to Jimmy Reed here, then, is the last line being an unambiguous reference to a musician: I can’t sing a song that I don’t understand. Which would be a bit wry; presumably due to his alcoholism, Reed increasingly struggled to remember his lyrics in later years, or even to remember when to start playing a solo on his guitar or harmonica. Especially on the records he recorded after 1969, when he was already unable to perform on stage, you can occasionally hear Mama Reed and Eddie Taylor coaching. Fortunately, it does little to detract from the quality – an LP like 1973’s I Ain’t From Chicago, for instance, is a soulful, funky blues performance that smoothly invades the no-man’s land in between Sly Stone, Stevie Wonder and Muddy Waters.

Still, Dylan paying tribute to anyone in particular with this one line is not too likely anyway. “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” thus gradually seems more like the reverie of an older fan leafing through the yellowed photo album of dusted memories, moving himself by dredging up half-forgotten, loose memories. Placing the song in the category of “nostalgic tribute songs”, all-encompassing songs paying homage to the blues in general, to blues pioneers and greats. Something like The Animals’ “Winds of Change”, like J.B. Lemoir’s “Down In Mississippi”, Van Morrison’s “Cleaning Windows”. Songs like “DJ Play My Blues” (1981) by Buddy Guy, who takes his hat off to T-Bone Walker in the first verse, to Howlin’ Wolf in the second, and in the last:

Will you listen to me please And spend me a song by the late Jimmy Reed Will you listen, listen to me please And spend me a song by the late Jimmy Reed Oh, you know you would make me feel kind of good Oh make me howl, oh yes indeed

Dylan’s “Goodbye Jimmy Reed” is – obviously – more poetic than the average tribute song, which is usually rather one-dimensional. “Bessie Smith was created in heaven above / Robert Johnson sang the blues,” Eric Burdon sings. “Heard Leadbelly and Blind Lemon on the street where I was born, yeah,” reveals Van The Man. “And I know no one can sing the blues like Blind Willie McTell,” says some other. All more one-dimensional than an homage like I can’t sing a song that I don’t understand, anyway, in itself a qualification applicable to every big name from Billie Holiday to Muddy Waters.

And apart from that, apart from its lack of specificity, it is a performance requirement that is almost something of a cliché. Dylan may once again have been triggered by Walt Whitman, this time by his “To A Certain Villain” (And go lull yourself with what you can understand–and with piano tunes), but sang it himself almost sixty years ago as well, of course; I’ll know my song well before I start singin’ (“A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, 1963), and just as unambiguously penned in that fascinating letter “For Dave Glover” in the Newport Folk Festival 1963 programme booklet:

“I’m still singin – I’m still writin

I’m still doin all a things I used to do I guess

But the difference is probably that now I really ain’t thinkin

about what I’m doing no more

I do worry no more bout the covered up lies and twisted truth in front

a my eyes

I don worry no more bout the no-talent criticizers an know-nothin

philosophizers

I don worry no more bout the cross-legged corner sitters who try an

make rules for the ones travelin in the middle a the room

I’m singin an writin what’s on my own mind now

What’s in my own head and what’s in my own heart

I’m singin for me an a million other me’s that’ve been forced t’gether

by the same feelin”

This is why I can’t sing “Little Maggie” or “John Henry” anymore, the young Dylan explains to “Dave”, and no more “John Johannah”… cause it’s his story an his people’s story. With the wisdom of hindsight, a first pre-announcement of Another Side Of Bob Dylan, then. Which is the stepping stone to Bringing It All Back Home – and eventually to “Goodbye Jimmy Reed”, a song Dylan does seem to understand. Being in his own heart, and all.

To be continued. Next up Goodbye Jimmy Reed part 9: She’s going to play you for a fool

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

J.B. Lemoir must be J.B. Lenoir (foutje zit ook in de boekversie).

Merci Robbert – attent van je om het even te melden.

Ik neem ‘m mee.