High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 1

by Jochen Markhorst

I London Bridge Is Falling Down

High water risin’—risin’ night and day All the gold and silver are being stolen away Big Joe Turner lookin’ east and west From the dark room of his mind He made it to Kansas City Twelfth Street and Vine Nothing standing there High water everywhere

“Joe Turner is always surprising me with little nuances and things,” Dylan tells Jeff Slate in the Wall Street Journal interview in 2022. The declaration of love is not really surprising; we have known Dylan’s appreciation for Big Joe Turner since the 1960s. Explicitly, in interviews, as a DJ on Theme Time Radio Hour, and on stage (he plays “Shake, Rattle And Roll”, for example, in 1991 with Keith Richards in Seville). And implicitly through references, nods and borrowings in his own songs. The big brass bed from “Lay, Lady, Lay” (1969) is probably borrowed from Turner’s “Cherry Red” (although both men may also have copied it from Blind Willie McTell’s “Rough Alley Blues” – I take it to my room and lay it ‘cross my big brass bed); in Dylan’s “Standing In The Doorway” we hear a snippet from Big Joe’s “Bull Frog Blues” (I left you standin’ here in your back door crying); “Boogie Woogie Country Girl”, the song Dylan recorded for the tribute album Till The Night Has Gone: A Tribute To Doc Pomus (1995) seems to be the template for Modern Times‘ opening song “Thunder On The Mountain” in 2006; and when Patti Smith invites drummer David Kemper for her podcast series A Bob Dylan Podcast in 2007 and asks about his studio experiences, Kemper talks about the so-called reference records Dylan has his band reenact:

“Joe Turner is always surprising me with little nuances and things,” Dylan tells Jeff Slate in the Wall Street Journal interview in 2022. The declaration of love is not really surprising; we have known Dylan’s appreciation for Big Joe Turner since the 1960s. Explicitly, in interviews, as a DJ on Theme Time Radio Hour, and on stage (he plays “Shake, Rattle And Roll”, for example, in 1991 with Keith Richards in Seville). And implicitly through references, nods and borrowings in his own songs. The big brass bed from “Lay, Lady, Lay” (1969) is probably borrowed from Turner’s “Cherry Red” (although both men may also have copied it from Blind Willie McTell’s “Rough Alley Blues” – I take it to my room and lay it ‘cross my big brass bed); in Dylan’s “Standing In The Doorway” we hear a snippet from Big Joe’s “Bull Frog Blues” (I left you standin’ here in your back door crying); “Boogie Woogie Country Girl”, the song Dylan recorded for the tribute album Till The Night Has Gone: A Tribute To Doc Pomus (1995) seems to be the template for Modern Times‘ opening song “Thunder On The Mountain” in 2006; and when Patti Smith invites drummer David Kemper for her podcast series A Bob Dylan Podcast in 2007 and asks about his studio experiences, Kemper talks about the so-called reference records Dylan has his band reenact:

“All right, the first song we’re going to start with is this song,” and he’d play it on the guitar and then he’d say “I want to do it in the style of this song,” and he’d play an early song. Like he started with Summer Days and he’d play a song called Rebecca by Pete Johnson and Big Joe Turner. . . . It was like, “Oh my God, he’s been teaching us this music [all along]—not literally these songs, but these styles.”

Kemper refers to the recordings for “Love And Theft”, confirming that Big Joe Turner also indirectly penetrates Dylan songs.

As a DJ, Dylan plays a Big Joe Turner record five times in his Theme Time Radio Hour, always framed with words of love and respect, and twice with more than just words of appreciation. Like the words the DJ chooses when he has played “The Chill Is On” in Episode 75 (2 April 2008, Cold):

“There’s also a line in that song: I been your dog ever since I been your man. Certain phrases are used over and over in the folk process, and are crossing the boundaries between country and blues music. A phrase like that one, or: I’m going where the chilly winds don’t blow can be heard over and over.”

… “certain phrases used over and over”, “crossing the boundaries between country and blues music” – exactly what Dylan loves to do in general and in extremis here in “High Water”; Dylan not only slaloms across the boundaries of country and blues, but also picks up gospel and folk in the first verse alone.

The first two words, high water, are obviously due to the song’s namesake, Charley Patton and his monumental 1929 “High Water Everywhere” part 1 and/or part 2. But apparently songwriter Dylan decides to honour a gospel monument in one fell swoop immediately afterwards;

Just listen how it’s raining, all day, all night

Water rising in the east, water rising in the west

… from the old spiritual “Didn’t It Rain” (believed to be from the late nineteenth century, first published in 1919), the classic about Noah’s flood that is in the repertoire of everyone from Mahalia Jackson to Johnny Cash and from Sister Rosetta Tharpe to Tom Jones, The Band and Dave Van Ronk. And in between, between water rising and night and day and east and west, there is then room for another reference. Again antique, and again well known:

Silver and gold will be stolen away Stolen away, stolen away Silver and gold will be stolen away My fair lady

… “London Bridge Is Falling Down” (or “My Fair Lady”, or “London Bridge”), the ancient nursery rhyme from the early eighteenth century, which Dylan might have picked up from his copy of Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (1744). At least, after namechecking “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (1965) and remodelling Tommy Thumb’s “Who Killed Cock Robin?” into “Who Killed Davey Moore?” (1963), it does seem plausible that Dylan tends to browse it every once in a while.

So far, the connotations of a freely associating Dylan, floating around on his stream of consciousness, can be followed. “High water” – Noah’s flood – collapsing bridges… it seems fairly straightforward. But then again, that does not go for the popping up of Big Joe Turner, halfway through. A somewhat obscure branch of the stream, one might suspect at first (thinking of deep cuts like “Rainy Day Blues” or ” Rainy Weather Blues”), or perhaps a Big Joe Turner recording is the reference record for “High Water”. Not very likely. The influence of “Rebecca” on “Summer Days” revealed by David Kemper is traceable. However, there is no song in Big Joe Turner’s oeuvre that approaches “High Water” – neither the tone colour, i.e. the sound, nor distinctive features like arrangement, stomp or even a lick are traceable. On those fronts, Dylan’s song creeps much closer to the Stanley Brothers or Bill Monroe, anyway.

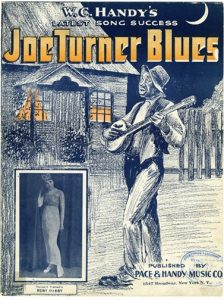

No, for the sake of convenience, we should maybe leave out the prefix “Big”, for now. A link to one of the foundations of blues, “Joe Turner Blues” is more obvious. The name “Joe Turner” pops up in several old blues and folk songs, and the best known is of course W.C. Handy’s evergreen from 1915. Handy draws on a nineteenth-century folk song for his hit, as he easily reveals himself:

“Following my frequent custom of using a snatch of folk melody in one out of two or three strains of an otherwise original song, I wrote Joe Turner Blues and adapted the twelve bars of Old Joe Turner as one of its themes. Here Joe Turner himself was no longer the long-chain man; he was the masculine victim of unrequited love just as the singer in St. Louis Blues was the feminine, and he sang sadly and yet jauntily.”

(W.C. Handy – Father Of The Blues, 1947, p. 146)

The various Joe Turners are: a sinister human trafficker; a released prisoner; a the deplorable victim of unrequited love, and in most “Joe Turners” the refrain survives: They tell me Joe Turner been here and gone. As it does in the Joe Turner variant that Dylan seems to be thinking of in the concept phase of “High Water”: Big Bill Broonzy’s “Joe Turner Blues”, the song that William Lee “Big Bill” Conley calls “the earliest blues I ever heard”, the song about a Good Samaritan helping people after a flood catastrophe. “It’s older than I am,” says Big Bill in his hotel room 1952 in Paris, in the interview conducted by Alan Lomax, “because I was born 1893, and my uncle sang it back in 1892. Now, I don’t know how long it was sung before then”:

This is a song was sung back in 18 and 92. There was a terrible flood that year. People lost everything they had. Their crops, their live stock, that means their horses, their mules, cows, goats and everything they had on their farm. And they would start cryin’ and singin’ this song:

They tell me, Joe Turner been here and gone Lord, they tell me, Joe Turner been here and gone They tell me, Joe Turner been here and gone

With that, with that three-step flood catastrophe – “Joe Turner Blues” – Big Joe Turner, the train of thought is again as clear as the water – Noah – bridge hopscotch; Joseph Vernon “Big Joe” Turner Jr. was born and raised in Kansas City, and has a “Kansas City Blues” of his own in his repertoire (a B-side from 1951), so the leap to Wilbert Harrison’s monumental “Kansas City” is quickly made. The song from which Dylan lovingly steals for “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” (they got some hungry women there is a little disguised derivation of Wilbert’s they got some crazy women there), the song from which he literally copies the now-nonexistent address Twelfth Street and Vine here, for “High Water”, and the song from which DJ Dylan said in 2006:

“Here’s a chart-topping smash by Mr. Wilbert Harrison, recorded for Bobby Robinson in 1959, and features the barbed-wire guitar of Wild Jimmy Spruill. Y’all know this song, and it always sounds good. Wilbert Harrison. Kansas City.”

(Theme Time Radio Hour episode 20, “Musical Map”).

Which may all make it reducible why Joe Turner surfaces here, in Dylan’s 2001 tribute to Charley Patton, but that still does not make Big Joe Turner a fitting guest. In any case, it is not a subconscious action of an autonomously rippling stream of consciousness. After all, the very first draft of the song, exhibited at the Bob Dylan Centre in Tulsa, does not yet feature Big Joe:

High water risin’ – putting lime in my face High water risin’ – it’s hard, leaving this place I’m looking as far to the East as the eye can see Trying to get a glimpse of what might be dreaming of an old love affair – High water’s everywhere

… but then the creating song poet is apparently soon determined to include Big Joe Turner – in that same draft we see no fewer than four variations in the right margin incorporating the name. The most wondrous is the last one:

The white cat bit the black cat – he said I’m not lonely but I feel alone

Both Joe Turner and Bertha Mason rode on Train 45 into the next time zone

“Write twenty verses while you’re in The Zone. You know, the last ones might be better than all the stuff you had,” is the advice Dylan gives to the studious Mike Campbell (as Mike tells us in Consequence Podcast, 9 March 2022). But complete derailment is apparently also possible, out there in The Zone.

Still: “better stuff” or not, those scraps in the margin do lift a second corner of the veil. Joe Turner and Bertha Mason rode on Train 45… the old folk song “Train 45” might just have been the reference record for “High Water”. Bill Monroe’s interpretation, or the one by The New Lost City Ramblers then. No wait, the Stanley Brothers, of course.

——

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B