by Jochen Markhorst

IV What’s so bad about misunderstanding?

I got a cravin’ love for blazing speed Got a hopped up Mustang Ford Jump into the wagon, love, throw your panties overboard I can write you poems, make a strong man lose his mind I’m no pig without a wig I hope you treat me kind Things are breakin’ up out there High water everywhere

We owe some fascinating insights to Larry Charles’ now illustrious 2014 visit to the podcast You Made It Weird. Foremost, the revelation about the “very ornate box” Dylan always seems to have with him, the box filled with “little scraps of paper” on which a wide variety of ideas are jotted down. Sometimes a single word or name, Charles explains, like “Uncle Sweetheart”, but mostly phrases. “He takes these scraps and he puts them together and makes his poetry out of that.” Like – apparently – a line eventually used not for the mythical slapstick comedy Charles and Dylan were working on at the time (which would somehow evolve into the weird, dystopian drama Masked And Anonymous, 2003), but for this song in 2001:

We owe some fascinating insights to Larry Charles’ now illustrious 2014 visit to the podcast You Made It Weird. Foremost, the revelation about the “very ornate box” Dylan always seems to have with him, the box filled with “little scraps of paper” on which a wide variety of ideas are jotted down. Sometimes a single word or name, Charles explains, like “Uncle Sweetheart”, but mostly phrases. “He takes these scraps and he puts them together and makes his poetry out of that.” Like – apparently – a line eventually used not for the mythical slapstick comedy Charles and Dylan were working on at the time (which would somehow evolve into the weird, dystopian drama Masked And Anonymous, 2003), but for this song in 2001:

“He would ask these questions that would come back and crack your mind open. One time he said to me… he had a line about a pig wearing a wig, and I was comfortable enough to say “Bob, that doesn’t make any sense, no one is gonna understand that.” And he said “what’s so bad about misunderstanding?” That’s like wow that’s a heavy one. Because we are striving all the time to be understood. He’s been understood. He’s more interested now in what happens when you’re misunderstood. He’s like Andy Kaufmann or something like that. Very, very kind of conceptual.”

Where, on a semantic level, you can argue about whether “nonunderstanding” would be a somewhat sharper qualification than “misunderstanding”, and it also seems that Larry has an entirely unique definition of “conceptual”, but the thrust of his analysis is clear; linear logic or simple cause-and-effect concepts are not a priority with Dylan. At least; not with Dylan in the 1990s, the time Larry Charles is talking about. Which, given Masked & Anonymous, “High Water” and the mosaic-like lyrics of Rough And Rowdy Ways (2020), we may extend to the present day.

The change in this third verse of “High Water” seems an extreme example thereof, of such a deliberate attempt to create “misunderstanding”. The first three lines, about speed and the Ford Mustang and the wagon into which a lady should jump with abandonment of her panties, still have a traceable relationship connecting them – the car, obviously. But then the poet slides a snippet from his “ornate box” to the manuscript, and suddenly “I can write you poems, make a strong man lose his mind” comes out of thin air. The narrator’s boastful mention that he is able to write such impressive poems might still fit in as a text from a smooth talker flirting with the now pantsless lady in the passenger seat, but the addition that those poems “can make a strong man lose his mind” is quite alienating. Mind deranging writings are of all times, of course, with the tragic Cyrano de Bergerac as the standard bearer, but these are actually always meant to make a female head spin – we have been conditioned for centuries now that poets use their brainchildren to woo the ladies.

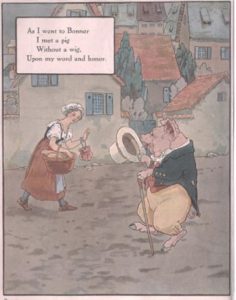

Before the raised eyebrows have had a chance to lower, however, they are raised some more: “I’m no pig without a wig,” clarifies the first-person behind the wheel of his hopped-up Mustang. A verse that, as we know thanks to Larry Charles, has been in Dylan’s clipping box for about a decade. Picked up from an ancient nursery rhyme, from

As I went to Bonner, I met a pig Without a wig. Upon my word and honour.

Published around 1830 by the legendary London printer and publisher James Catnach in the nursery rhyme collection Nurse Love-Child’s New Year’s Gift for Little Misses and Masters, but believed to have been sung much earlier, as early as 1760. The collection in which Dylan also will have noticed “Who Killed Cock Robin?”, which provides the template for “Who Killed Davey Moore?” (1964), and filled with nursery rhymes that appeal to Dylan’s penchant for punchless absurdity. Like the story of Jack-a-Nory;

I’ll tell you a story About Jack-a-Nory, And now my story 's begun, I’ll tell you another About Jack and his brother, And now my story 's done.

… which has now entered the dictionaries as jackanory; by qualifying something as “jackanory”, you indicate that you think the other person is making up or stretching a story – or lying, even. “Not making any sense,” Dylan would probably add.

The alienating intruder with a wig does not stand alone, in this whimsical verse. The tone of the follow-up I hope you treat me kind does not fit at all with the macho talk of the Mustang driver either, with the stud who gruffly orders some nice girl to jump in the car and throw her panties overboard. “I hope you treat me kind” is vulnerable, an appeal of a sensitive, insecure guy with a slight undertone of despair. Quite exclusively reserved for soul ballads, actually, although a first use can be found all the way back in the dustclouds around the Big Bang, in “Aggravatin’ Papa”;

Aggravatin' Papa, don't try to two-time me! Aggravatin' Papa, treat me kind or let me be

… popular in the 1920s, recorded by matriarchs such as Florence Mills, Alberta Hunter and Bessie Smith.

Still, the fragile, in later years the somewhat tearful plea has been confiscated by soul masters like Ray Charles (“The Sun’s Gonna Shine Again”, 1953, the song with the frenzied trumpet), The Temptations (“You’ve Got To Earn It”, 1964), or the most beautiful of all, “I Don’t Know What You’ve Got (But It’s Got Me)”. Little Richards’ last single for Dylan’s beloved Vee-Jay Records from 1965, featuring the young promising James Marshall Hendrix on guitar;

You never treat me kind You party all the time You don’t mean me no good I'd leave you if only could Baby I don't know what you got Honey I don't know what you got But it's got me, I believe it's got me

A sparkling soul diamond that, in retrospect, makes it all the more regrettable that Little Richard did not feel the urge to fill the gap left by Sam Cooke and Otis.

Anyway – all hurt, vulnerable suckers, incomparable to the bragging hotshot behind the wheel of the Mustang. No, then still more comparable to a hog wearing a hairpiece, indeed.

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 5: Maybe we should put that there

———–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B