High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 5

by Jochen Markhorst

V Maybe we should put that there

I got a cravin’ love for blazing speed

I got a cravin’ love for blazing speed

Got a hopped up Mustang Ford

Jump into the wagon, love, throw your panties overboard

I can write you poems, make a strong man lose his mind

I’m no pig without a wig

I hope you treat me kind

Things are breakin’ up out there

High water everywhere

Aragon is initially an anonymous hobbit who is good at making wooden shoes, in a subsequent version the rightful King of the Hobbits, in the third version he is called Strider, and only in the manuscript after that Strider is a code name for Aragon. Suddenly he is human, and Tolkien decides that Aragon is actually the heir to the throne of Arnon and Gondor. From nameless clogmaker with hairy feet to Middle-Earth’s most powerful king – it’s quite a career.

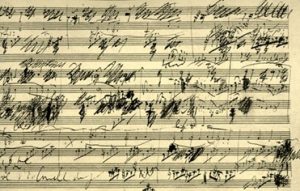

Beethoven’s manuscripts are violently ploughed battlefields, Chopin thoroughly shades entire bars, and thanks to Wilhelm Röntgen, we know what the first sketches of Rembrandt’s Night Watch and Vermeer’s Milkmaid looked like, we find unknown self-portraits by Van Gogh and an overpainted portrait under Picasso’s Blue Room.

Manuscripts, sketchy drafts, first versions and crossed-out passages… they are, obviously, not meant for the public or for perusal, but if those disapproved versions are the precursors of masterpieces, they offer an irresistible, almost voyeuristic pleasure. Rarely on an aesthetic level, of course – usually the master rejected them for a reason. But for fans they offer fascinating insight into the creation of masterpieces. 2015’s The Bootleg Series 12 – The Cutting Edge 1965-66 is the shiniest example on Planet Dylan; 18 CDs on which we can follow the creation of such highlights as “Visions Of Johanna”, “Like A Rolling Stone” and “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry” almost in real time.

Less spectacular, but at least as fascinating, are the draft versions of song lyrics. After all, they offer the opportunity to peek into the creative part of an admired artist’s mind – in this case even of a Nobel Prize-winning genius. Process descriptions we have heard many times. From fellow artists, from studio personnel and from Dylan himself, who tries often enough, both in Chronicles and in interviews, to explain how his lyrics come about. Most of the time, by the way, the mystery only deepens. “They just fall from space”, “I’ll play a Bob Nolan song in my head, and at a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song”, “All those early songs were almost magically written” … no, then we learn more from Larry Charles’ testimony, who reveals how Dylan saves one-liners and word combinations on paper scraps, and starts “writing” by shuffling and puzzling. Or from Mike Campbell’s revelation in the Consequence Podcast, 9 March 2022:

“He told me once, which was a really good tip, he said, when you’re writing a song, you know, you got your verses, your bridge and your chorus, he said, don’t stop there. Write twenty verses while you’re in The Zone. You know, the last ones might be better than all the stuff you had.”

A combination of Charles’ cut-and-paste revelation and Campbell’s description then seems to be exposed here, in the manuscript of “High Water”. And especially in this third stanza;

comin’ like a whirlwind

3. High Water Risin’ tryin to suck me in (at f like Hucklbery Finn)

James Joyce just walked in the door like he’d been in a whirlwind

It’s probably the way baby where you been (rain and wind) (like whirlwind)

Got to get out ahead of the hound get my pistol off the shelf

He said I believe that as great as you are, you’re never I’m telling

Got to believe that you’re alive, at least that’s what to tell yourself

Sometime ( Maybe) pray the sinner’s prayer I’m prayin’ the Sinners

He says I said man – it’s wet

Not a single word survives in the final version of this third verse. One inspiration from, let’s call it, the “second draft” (the interjected verse lines and loose fragments in blue) eventually moves to the sixth verse, half of As great as you are, man, you’ll never be greater than yourself. We see James Joyce and Huckleberry Finn pop up, both of whom will fade away again. We decipher that, in both the first and second versions, Dylan is considering to incorporate something with “like a whirlwind”.

Equally desirable, apparently, is a reference to the narrator’s devout disposition – the sinner’s prayer, at least, still survives the first cut as well, but eventually moves to the song “If You Ever Go to Houston”, re-appearing eight years later on Together Through Life (“Tell her other sister Betsy / To pray the sinner’s prayer”). And the hard to decipher primal fragment Got to get out ahead of the hound seems to be a reference to Robert Johnson’s 1937 “Hellhound On My Trail”. Perhaps triggered by ominous lyric passages like Blues fallin’ down like hail and I can tell the wind is risin’ in Johnson’s song. Just as get my pistol off the shelf might be an echo from another blues staple, “Mad Mama’s Blues”, recorded in the 1920s by both Josie Miles and Julia Moody – and both bloodthirsty ladies sing I took my big Winchester down off the shelf.

Apart from those fascinating wanderings in content, apart from intriguing name-checks like James Joyce and Huckleberry Finn and the Sinner’s Prayer, the manuscript also grants us insight into stylistic considerations. Originally, then, the poet Dylan again lets this third stanza begin with the words High water risin’, opting thus for an anaphora, for a recurring verse line as the opening of each stanza, that is. We know the figure of speech mainly from rhetoric, of course (MLK’s I have a dream, Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, Churchill in just about every speech). In songwriting it is less common, though not unique. Dylan’s own 1967 Basement ditty “Don’t Ya Tell Henry” has the structure, for example (each stanza beginning with I went down to…), Psalm 29 starts each verse with The voice of the Lord, Kylie Minogue’s “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head”, T. Rex’s “Metal Guru”… through the centuries the repeated opening line is used, but not too often.

So the manuscript now suggests that the poet Dylan is ultimately trumped by the musician Dylan. It does seem that the poet was charmed by the anaphora, by the stylistic device of beginning each stanza with High water risin’. Perceivable; it is a choice that a Poe or a Baudelaire would also have made, a choice made by poets striving for a total fusion of sound and content. The two stressed i-sounds suggest a rise; the repetition communicates the inevitable, irrepressibly swelling threat of the flood. But then the musician Dylan intervenes; we’ve had two verses, now there should be something like a bridge or a chorus – a break, anyway. The repetition, and with it the unstoppable swelling of the flood, might just as well be communicated by the music, the musician Dylan knows. Which then in fact does come about, as Tony Attwood soberly and aptly analyses:

“The song is about the ceaseless rain, so Bob makes the song ceaseless by having it all based on one chord, and we have an unrelenting accompaniment containing as it does, a very clear rhythm.”

(High Water, a rise, a fall, a bounce, a flood, Untold Dylan, 5 November 2023)

… and then a sophisticated use of stylistic devices is no longer that important, apparently – the music succeeds in providing that coveted fusion of sound and content. The accompanying words no longer need to perform that function. Which is also illustrated by engineer Chris Shaw’s recollections, in Uncut, October 2008:

“There was a lot of editing done on “Love And Theft”. Like, the song “High Water”, for example, the verse order of that was changed quite a few times, literally hacking the tape up. He was like, “Nah, maybe the third verse should come first. And maybe we should put that there.”

Things are breakin’ up out there. High water everywhere.

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 6: The Levee’s Gonna Break

—————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B