by Jochen Markhorst

XIII The sum of its parts

The Cuckoo is a pretty bird, she warbles as she flies I’m preachin’ the word of God I’m puttin’ out your eyes I asked Fat Nancy for something to eat, she said, “Take it off the shelf— As great as you are, man, You’ll never be greater than yourself.” I told her I didn’t really care High water everywhere

“You just gotta remember that the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts,” says DJ Dylan in 2008, in that same fictitious phone conversation with listener Charles from Bloomington. Essentially the same as his rebuttal in the New York Times in 2020, to interviewer Douglas Brinkley’s question about the significance of Anne Frank next to Indiana Jones in the opening song of Rough And Rowdy Ways, “I Contain Multitudes”. You shouldn’t take it out of context, Dylan corrects, those names don’t stand alone;

“You just gotta remember that the whole is bigger than the sum of its parts,” says DJ Dylan in 2008, in that same fictitious phone conversation with listener Charles from Bloomington. Essentially the same as his rebuttal in the New York Times in 2020, to interviewer Douglas Brinkley’s question about the significance of Anne Frank next to Indiana Jones in the opening song of Rough And Rowdy Ways, “I Contain Multitudes”. You shouldn’t take it out of context, Dylan corrects, those names don’t stand alone;

“It’s the combination of them that adds up to something more than their singular parts. To go too much into detail is irrelevant. The song is like a painting, you can’t see it all at once if you’re standing too close. The individual pieces are just part of a whole.”

… hardly varying from the much-quoted 1985 reflection, from the Bill Flanagan interview, in which he unleashes a structural analysis on his own 1970s masterpiece “Tangled Up In Blue”: “When you look at a painting, you can see any part of it or see all of it together. I wanted that song to be like a painting. […] You’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room.”

Indeed, Dylan’s conception of art leads to exceptional beauty and breathtaking poetic explosions as in songs like “Tangled Up In Blue” and “I Contain Multitudes”. And to exceptionally challenging lyricism – as in the opening triplet (actually an ordinary distich which for unclear reasons is structured in the official publication as three verses) of this sixth verse of “High Water”, with seemingly incompatible singular parts:

- The Cuckoo is a pretty bird, she warbles as she flies - I’m preachin’ the word of God - I’m puttin’ out your eyes

A borrowed verse from an ancient folk song, a creed and a sadistic threat – it is quite a challenge to understand these individual pieces as just part of a whole.

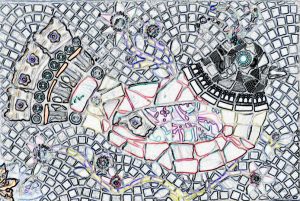

Unified within themselves, perhaps, this combination of them. After all, supplier “The Coo Coo Bird” is a textbook example of a mosaic-like song made up of separate, totally unrelated parts in terms of content. In all variations actually, but certainly in Dylan’s source, the Clarence Ashley version.

Three stanzas, the first of which announces that the first-person intends to build a log cabin somewhere on a mountaintop, in order to observe one Willie (“So I can see Willie as he goes on by”); the second stanza is the song’s namesake, the one praising the cuckoo’s singing talent, which strangely enough is not showcased until after 4 July; and the third stanza, again, has nothing to do with the previous one:

I've played cards in England I've played cards in Spain I'll bet you ten dollars I'll beat you next game

Clarence Ashley – The Coo-Coo Bird (1929 recording):

https://youtu.be/M6gATqj4qp8

… any relation to a lonely log cabin or a talented songbird is untraceable. And yet the song has been popular for more than two hundred years – apparently “The Coo Coo Bird” has a special, almost magical power that keeps us fascinated. The power Dylan refers to throughout the decades when he adores old folk songs:

“There are some really strange, weird folk songs, you know, that have come down through the ages, based on nothing. Based on a legend or Bible or, you know, plague or… or religion, and just based on mysticism.”

Dylan says this back in 1965, in the Playboy interview with Nat Hentoff, in the same weeks that he says pretty much the same thing to Nora Ephron and Susan Edmiston for the New York Post: “Folk music is the only music where it isn’t simple. It’s weird, man, full of legend, myth, bible and ghosts.” In the twenty-first century, Dylan professes his awe less poetically but all the more definitively: “Folk music is where it all starts and in many ways ends” (Rolling Stone interview with Mikal Gilmore, 2001), and in between, in 1997, he puts the religious component on thickest:

“My songs come out of folk music,” he says. “I love that whole pantheon.” […] “Those old songs are my lexicon and my prayer book,” he adds. “All my beliefs come out of those old songs, literally, anything from Let Me Rest on That Peaceful Mountain to Keep on the Sunny Side. You can find all my philosophy in those old songs. I believe in a God of time and space, but if people ask me about that, my impulse is to point them back toward those songs. I believe in Hank Williams singing I Saw the Light. I’ve seen the light, too.”

(John Pareles interview, New York Times, 1997

The Carter Family – Keep On The Sunny Side:

Which apparently triggers the songwriter Dylan to post the creed “I’m preachin’ the word of God” after a snippet from such a strange, weird folk song – insinuating that “The Cuckoo Is A Pretty Bird” is also such a song from his “lexicon”, such a song full of legend, myth, bible and ghosts, such a song that qualifies for being the word of God. And in line with that statement in the New York Times interview four years before the recording of “High Water”, the statement that he finds his God of time and space in old folk songs, that is.

However, there does not seem to be a biblical link to the subsequent macabre threat I’m puttin’ out your eyes. At least, as divine punishment, it does not actually appear. Blindness is only brought up anecdotally, to illustrate God’s forgiveness (after Samson’s eyes are put out by the Philistines) or to demonstrate Jesus’ miraculousness, to show that he truly is the Son of God. The healing of Bartimeus, for example (Mark 10:46-52), and the beggar in John 9.

Still, we do encounter a similar threat in that chapter, from Jesus himself, note: “For judgment I am come into this world, that they which see not might see; and that they which see might be made blind” (John 9:39). With that, the second and third verse lines in this verse of Dylan’s song would actually have a substantive connection – after all, Jesus is indeed preaching the word of God, and indeed expresses something like “I put out your eyes” here in John 9.

An unintended connection, presumably. A more likely, and also more attractive, scenario is that the song poet here at a micro level lays out a mosaic with side by side a folksong, a biblical reference and, finally, a pinch of world literature – after all, “putting out eyes” is a popular punishment with both nineteenth-century giants like Poe and Jules Verne, as well as in Greek mythology, and especially – to stay close to Dylan’s favourites – with Shakespeare. King Lear, of course, but especially King John, in which Shakespeare even uses the same words: “If an angel should have come to me and told me Hubert should put out mine eyes I would not have believed him” (Act 4, scene 1).

More prosaic, finally, is the cinematic link. Dylan is no doubt familiar with John Huston’s film adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s exceptional “Southern Gothic novel” Wise Blood. The 1979 film of the same name is a black comedy in which Dylan’s pal Harry Dean Stanton plays one of the main supporting roles as Asa Hawks, the preacher who simulates being blind – and in which the protagonist Hazel Motes, the atheist preacher and founder of the Church of Truth Without Jesus Christ Crucified deliberately blinds himself with quicklime.

All the more likely, this connection, when years after the release of “High Water”, we face the first draft version, which includes as its first line High water risin’ – putting lime in my face. Poignant and memorable enough in any case to twirl down as a distorted reflection in a Dylan song thirty years later, as a preacher putting out eyes.

However, the verses remain either way, with or without Shakespeare, with or without Harry Dean Stanton, and with or without Jesus, singular parts, and to see a whole that is bigger than the sum of its parts, we need to take a few more steps back, probably.

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 14: Just grab something off the shelf

——–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B