by Jochen Markhorst

XIX Water’s gonna overflow

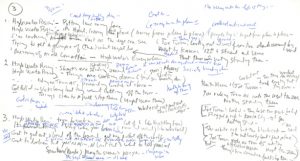

It does show a circled “3” at the top, but the draft version photographed by the Rolling Stone journalist when he visited the Bob Dylan Centre archives in 2017 does seem to be the very first version anyway – perhaps Dylan put the 3 above it because this was page 3 of a notebook. Or perhaps because he came up with three variants (two in black, the third in blue) on this draft alone. The opening couplet of this – supposed – primordial version can still be deciphered reasonably well:

It does show a circled “3” at the top, but the draft version photographed by the Rolling Stone journalist when he visited the Bob Dylan Centre archives in 2017 does seem to be the very first version anyway – perhaps Dylan put the 3 above it because this was page 3 of a notebook. Or perhaps because he came up with three variants (two in black, the third in blue) on this draft alone. The opening couplet of this – supposed – primordial version can still be deciphered reasonably well:

High water risin’ – putting lime in my face High water risin’ – it’s hard, leaving this place I’m looking as far to the East as the eye can see Trying to get a glimpse of what might be Dreaming of an old love affair – high water’s everywhere

Presumably primal version, as Joe Turner is not yet mentioned. A name Dylan seems to want to have in there pretty soon after scribbling down this first draft; we see in brackets next to line 3: Joe Turner looking east and west from the dark room of his mind, the line that will eventually be chosen with the addition “Big”, and below three more variants with “Joe Turner”.

In the other so-called “draft manuscript”, the version printed on page 496 in Mixing Up The Medicine, the third line is “Joe Turner he got away (tried to)” and something with “Got to Kansas City / Got no place to play” – which seems to confirm that this draft version was written later than the version without “Joe Turner”. Also illustrating once again, incidentally, that “Big Joe Turner” is a last-minute addition, and that at the creation stage Dylan had the protagonist from the antique folk song “Joe Turner” in mind.

Wynton Marsalis & Eric Clapton Joe Turner’s Blues:

More revealing than that relatively weightless Joe/Big Joe switch is the tenor of this primal couplet, suggesting an entirely different slant from what the cultural-historical mosaic “High Water” eventually became.

It seems that the opening words high water risin’ were the trigger, the catalyst, as Dylan will call it 2020 (New York Times interview, on the Walt Whitman quote I contain multitudes), and that the stream of consciousness initially leads him to lyricism like in 1967’s Basement gem “Down In The Flood (Crash On The Levee)”: metaphorical use of “high water”, “flood” and “levee crash”, to express the state of mind of a man who has had enough of his wife. Here we have a narrator who is “leaving this place”, looking for a new future (looking East, trying to get a glimpse of what might be), stone-faced (lime in my face), and who muses on a previous, presumably long-forgotten love interest; he is a man who is again “dreaming of an old love affair”.

The gentler version, all in all, of the narrator in “Down In The Flood”, who snarls at his wife “don’t you make a sound”, growls “pack up your suitcase”, a man who “refuses” her and tells her to take the train, and advises her to “find another best friend”. Meanwhile, the metaphors the narrator uses to express his displeasure are identical to “High Water”: high tide’s risin’, crash on the levee, water’s gonna overflow, go down in the flood.

The Derek Trucks Band – Down In The Flood:

It is quite likely that Dylan, with his documented aversion to repetition, would also see, no later than after about four of five lines into the conception stage, the similarity to his sneering song from over 30 years before. “Down In The Flood” is, after all, one of those few songs for which he still feels affection after the Basement months. Indeed, it is not unlikely that “Down In The Flood” (or “Crash On The Levee”; the titles are used interchangeably) was an initial trigger for “High Water” in the first place. After “Down In The Flood” is polished, it gets an honourable place on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. II in 1971: the re-recorded version with Happy Traum is the bestseller’s finale. A few weeks after the release of the double album, Dylan steps on stage at The Band’s New Year’s Eve concert in New York (1 January 1972) to play four songs with his old compadres, and “Crash On The Levee (Down In The Flood)” is the opening track. After that, the song slowly gathers dust – Dylan doesn’t look back at it for over 20 years.

But then it’s 1995, and Dylan starts his spring tour in Prague on 11 March, opening the concert with the pleasant surprise “Crash On The Levee” in a considerably roughened version with stadium rock-like Rolling Stones quality. It does please; the song stays on the setlist and is used 88 times as a concert opener in 1995. Ditto in ’96 and ’97; dozens of times on the setlist, always as an opener. In the run-up to the recording days for “Love And Theft” (8-21 May 2001), Dylan plays the song less often, and “Crash On The Levee” is no longer the opener, but the song is still alive – two days before Dylan goes into the studio, 6 May 2001, he plays the song in Memphis, as number six on the setlist.

It is further notable that the last three performances of the song (4, 5 and 6 May) are each preceded by the cover of the time-honoured Roy Acuff song “This World Can’t Stand Long” (1947), the song Dylan has been performing with some regularity since 2000 – always respectful and quite authentical acoustic performances, usually with Larry Campbell on mandolin, Charlie Sexton and Dylan acoustic guitar,Tony Garnier on upright bass and modest drum accompaniment by David Kemper, ending with the chorus as a fine three-part a cappella. In an arrangement, in short, that is already suspiciously close to the studio recording of “High Water”. The substantive link with “Crash On The Levee” – and by extension with “High Water” – is of course obvious:

This world was destroyed before Because it was so full of sin And for that very reason now It's gotta be destroyed again

… after all, Roy Acuff’s song recalls the greatest flood of all.

So on 4, 5 and 6 May, Dylan plays “This World Can’t Stand Long” plus “Crash On The Levee” sisterly side by side, and on Tuesday 8 May he enters the studio in New York for the recording of “Love And Theft”. The first two days are spent taping “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum”, “Summer Days” and “Honest With Me”, Thursday and Friday the band is off, Saturday 12 May is spent recording “Bye And Bye” and “Floater”, then three days off, and from Wednesday 16 May to Saturday 19 May the rest of the album is recorded (and on Monday 21 May another recording day is dedicated to the Time Out Of Mind-outtake “Mississippi”). Thursday 17 May is reserved for “High Water”. Two takes, the first being chosen for the album.

An educated guess is that Dylan wrote “High Water (for Charley Patton)” in the days leading up to its recording. We owe the clearest indication of this to engineer Chris Shaw’s testimony in Uncut, the revelation that “a lot of editing” took place, and that the editing included the verse order of “High Water” – apparently the song was not yet finished when recording began.

The most likely scenario for the creation process is then, all things considered:

– in the week before Dylan goes into the studio, he plays the combination “This World Can’t Stand Long” with “Crash On The Levee” three times; the word combination high water risin’ is now floating somewhere in the upper stream of his prefrontal cortex;

– high water risin’ floats almost naturally into an already deepened navigation channel, the channel dug à l’improviste in the Basement by “Crash On The Levee” 34 years ago;

– after a few lines Dylan notices this too, but thankfully the rhyme finding old love affair / everywhere opens new vistas – high water’s everywhere leads the flow of thought to Charley Patton.

At least, that apostrophe -s in high water’s everywhere seems to tell us that Charley Patton’s “High Water Everywhere” was not the catalyst, but suddenly comes out of the blue now. “None of those songs with designated names are intentionally written,” Dylan says in that same 2020 New York Times interview, “they just fall down from space. I’m just as bewildered as anybody else as to why I write them.”

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 20: Odds and Ends

Details of our other series can be found on the home page

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

Great article thanks for publishing! I like how it hearkens back, and draws parallels to “Down In The Flood (Crash On the Levee)” and alludes to Roy Acuff cover. Very well researched and organized along with visuals and recordings.

This song can be representative of so many things in our world today in a metaphorical sense. I think”High Water…” can be viewed from a number of perspectives like most, if not all, of Bob’s material. Bob’s lyrics are so open; often underpinned by nuances and combinations of: social – political -spiritual – and many more as well as some personal aspects. If you even consider it from an environmental view it evokes the current global warming struggles.