High Water (for Charley Patton) (2001) part 21

by Jochen Markhorst

Maybe you noticed that most of my songs are traditionally rooted. I don’t do that on purpose. Charley Patton’s 30’s blues has made a deep impression on me and High Water (for Charley Patton) is, in my opinion, the best song of this record,” says Dylan at the Rome press conference, July 2001.

I do agree. Well, ex aequo with “Mississippi”, anyway. Both songs open the floodgates (no pun intended), and “High Water” belongs in the same outer category as “Desolation Row”, “Mississippi” and “I Contain Multitudes”; extremely rich, poetic, Nobel Prize-worthy musical gems. Lovely, lovely song.

———————-

The album’s namesake, Eric Lott’s Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class from 1993, leaves no other recognisable traces on Dylan’s album. Lott himself doesn’t see any either. In 2017, in his book Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism, he devotes a chapter to Dylan, but then limits himself to generalities. “I would guess that Dylan regards minstrelsy, say, whatever its ugliness, as responsible for some of the United States’ best music as well as much of its worst,” for example, and he speculates Dylan “wants to step up and face the racial facts of one of the traditions he inherited.” Which seems debatable, to say the least. Indeed, from the draft versions of “High Water” one might even conclude the opposite, one might infer that Dylan is instead stepping back and facing away.

The album’s namesake, Eric Lott’s Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class from 1993, leaves no other recognisable traces on Dylan’s album. Lott himself doesn’t see any either. In 2017, in his book Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism, he devotes a chapter to Dylan, but then limits himself to generalities. “I would guess that Dylan regards minstrelsy, say, whatever its ugliness, as responsible for some of the United States’ best music as well as much of its worst,” for example, and he speculates Dylan “wants to step up and face the racial facts of one of the traditions he inherited.” Which seems debatable, to say the least. Indeed, from the draft versions of “High Water” one might even conclude the opposite, one might infer that Dylan is instead stepping back and facing away.

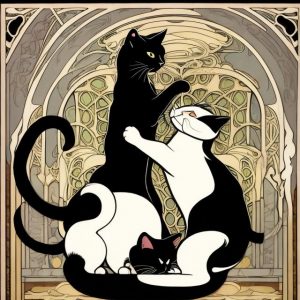

We do, at any rate, decipher at the bottom of the second verse of the – presumably – first draft:

White cat just put out the black cat’s eye

… about which the freewheeling songwriter is not entirely dissatisfied at the conception stage; on the right-hand side of the sheet, among three “Joe Turner” variants with and without “Bertha Mason” and with and without “Train 45”, there is a fairly readable verse:

The white cat bit the black cat – he said I’m not lonely but I feel alone

It is a remarkable mosaic piece for “High Water”, which, after these two attempts, is nevertheless put back in the box, in the famous very ornate box of Dylan’s loose ideas and lovingly stolen fragments; the apparently non-fitting puzzle piece combines two worlds. The second part, he said I’m not lonely but I feel alone, is one of many phrases and word combinations Dylan draws from the work of Henry Rollins. Originating again, after the many borrowings on the previous album Time Out Of Mind and after “dark room of my mind” in this “High Water”, from the poignant Now Watch Him Die, the diary-like work from 1993 in which Rollins processes his post-traumatic stress after his best friend is shot dead right in front him in a brutal street robbery. In the excerpt 26 April, New York, we read:

“I cannot translate the language of exhaustion. I feel alone but I’m not lonely. The walls understand me better.”

… which does seem a rather irrefutable source for Dylan’s rejected verse. Interesting, but of course no longer too surprising – by now, we know the special status of royal purveyor Rollins. More surprising then is the source of the first part of the verse, from The white cat bit the black cat and the first lead-up to it, White cat just put out the black cat’s eye. Which can no doubt be traced back to

My sister Rose de oder night did dream, Dat she was floating up and down de stream, And when she woke she began to cry, And de white cat picked out de black cat’s eye.

… to the fourth verse of the antique “Jim Along Josie”.

“Jim Along Josie” is a hit from the heyday of blackface minstrelsy (roughly 1840-70), written in 1838 by Edward Harper. “A wildly popular song, ‘that first-rate ballad,’ known by everyone,” as banjo player Carson Hudson Jr. writes in the liner notes of his LP I Come From Old Virginny! Early Virginia Banjo Music 1790-1860 (2003).

Traces of minstrelsy do appear in Dylan’s oeuvre these years. The name-check “Mr. Jinx and Miss Lucy” in the 2000 Oscar-winning “Things Have Changed”, for example (“Miss Lucy Long”, written around 1840, is one of the most popular blackface minstrel songs; Mr. Jinx a black stereotype from the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920’s). The appearance of a blackface artist in Dylan’s film Masked And Anonymous (2003, a black-faced Ed Harris as the ghost of “Oscar Vogel”); the Al Johnson songs he gives the musicians on Time Out Of Mind as homework; the quotes from Box and Cox, a blackface minstrel skit from 1856, in the opening song of “Love And Theft”, “Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum”… there are some lines to be drawn to blackface minstrelsy, and thus to Eric Lott’s standard work. More so, however, as again Scott Warmuth demonstrates, to musicologist Dale Cockrell’s 1997 study Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and their World, in which, in addition to the term masked and anonymous, we find an extensive analysis of both lyrics and music of “Jim Along Josie”.

But with that, Dylan apparently thinks it is enough. After two attempts to allow another sample of “inherited tradition”, as Lott calls it, into a song on “Love And Theft”, Dylan leaves the quote from a blackface song from over a century and a half ago on the cutting floor – stepping back and facing away. Too unsubtle, perhaps, this particular quote with imagery imposed a little too thickly.

True, the songs usually demonstrate mockingly and racially motivated stupidity or laziness of the black fellow man, larded with simple puns and half-obscene asides, but there are songs like “Jim Along Josie” as well, in which veiled some suffering is sung, with or without references to cruelty from white bosses. In “Jim Along Josie”, The white cat picked out the black cat’s eye is the only verse line with such a charge, so it seems to say something that Dylan initially picks out this very line. The preceding lines, describing Rose’s dream, the dream in which she drowns in a river, would obviously have fitted much better in terms of content to “High Water”, to a song in which “flooding” is a motif.

Anyway – after Dylan thickens the white violence a little more in a second variation (The white cat bit the black cat), the line disappears for good, and with it the mosaic pebble “blackface 19th century”. At least: as yet, we haven’t heard it in a Dylan song.

In “Scarlet Town” (Tempest, 2012), we still encounter a half-hearted reference to “racial facts”, as Eric Lott calls it (The black and the white, the yellow and the brown / It’s all right there for ya in Scarlet Town), and in 2020, another name-check of sorts follows in “Murder Most Foul” (Blackface singer, whiteface clown / Better not show your faces after the sun goes down), but that’s about it.

Yeah well. With or without the catfight, “High Water” is a first-rate ballad anyway, of course.

—-

To be continued. Next up High Water (For Charley Patton) part 22: The Ghost of Herman Melville

—-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B