I don’t know what it means either: an index to the current series appearing on this website.

by Jochen Markhorst

When I Paint My Masterpiece part 1: She’s delicate and seems like a Vermeer

II Oh, the streets of SoHo

Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble Ancient footprints are everywhere You can almost think that you’re seein’ double On a cold, dark night on the Spanish Stairs Got to hurry on back to my hotel room Where I’ve got me a date with Botticelli’s niece She promised that she’d be right there with me When I paint my masterpiece

All in all, it is a fascinating account, Leon Russell’s account in Doggett’s article “Whose Masterpiece Is It Anyway?”. And mainly because it gives us such an unusual glimpse into such an unusual genesis of two unusual Dylan songs. Russell testifies that Dylan plucked the lyrics out of thin air on the spot, and that’s believable. After all, we know plenty of similar stories. About the creation of songs in the Basement, for example, both from Garth Hudson (in the moving 2014 Rolling Stone documentary “Garth Hudson Returns to Big Pink”):

All in all, it is a fascinating account, Leon Russell’s account in Doggett’s article “Whose Masterpiece Is It Anyway?”. And mainly because it gives us such an unusual glimpse into such an unusual genesis of two unusual Dylan songs. Russell testifies that Dylan plucked the lyrics out of thin air on the spot, and that’s believable. After all, we know plenty of similar stories. About the creation of songs in the Basement, for example, both from Garth Hudson (in the moving 2014 Rolling Stone documentary “Garth Hudson Returns to Big Pink”):

“Bob didn’t like to sing the same song over and over again. Sounds to me like he did make up songs on the spot. (…). I think “Sign On The Cross” was done in real time. Both the composition and the execution thereof.”

https://youtu.be/FKz8HQKyc4w

And we know similar testimonies from the autobiographies of Robbie Robertson (“His ability to improvise on a basic idea was truly exceptional and a lot of fun to witness”) and Levon Helm (on Planet Waves: “Bob had a few songs and wrote the rest in the studio”), from drummer David Kemper on “Cold Irons Bound” (1997) or from George Harrison on “Handle With Care”, to name but a few – Dylan has the gift of dashing off lyrics almost on command.

For Jim Keltner, the drummer, the session on 16 March 1971 was the first experience with Bob Dylan. As he recalls the memory of that special moment, his story is largely in line with Russell’s account, but he does build in a little disclaimer:

“He had a pencil and a notepad, and he was writing a lot. He was writing these songs on the spot in the studio, or finishing them up at least. And the rest of us, we just started playing, jamming around on some different chords and things, and finally the song came together, Bob came over, and we recorded them: “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece”. Those two songs were done really quickly.”

(Uncut, 17 October 2008)

“… or finishing them up at least,” Keltner still hesitates, but Leon Russell is pretty sure that the entire lyrics are made up on the spot; both his memory He let me watch him as he wrote and Bob got his pad out and started walking around, writing stuff down. I followed him around the room, watching him as he was writing suggest that Dylan starts on a blank page, filling it while Russell rewinds the tape and plays the track again and again. The first song recorded is “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, so it is plausible that it is also the first lyric Dylan constructs here in the Blue Rock Studio under Leon’s watchful eye.

The theme of both songs seems taken from life; Dylan himself is in an unproductive, inspirationless phase. These are the dry years after the prolific war of attrition that was the 1960s, a dry spell which he himself explains in his autobiography Chronicles as:

“Art is unimportant next to life, and you have no choice. I had no hunger for it anymore, anyway. Creativity has much to do with experience, observation and imagination, and if any one of those key elements is missing, it doesn’t work.”

But apparently – paradoxically – it inspires two songs today that have an inspiration-seeking creator as their protagonist. The opening line, Oh, the streets of Rome are filled with rubble, remains unchanged in all alternative and later versions – presumably that line is the catalyst, as Dylan calls it. And indeed, it does seem Dylan draws that line today from experience, observation and imagination.

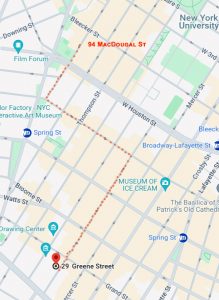

Blue Rock Studio is located in SoHo, at 29 Greene Street. That’s less than a 15-minute walk from Dylan’s pied-a-terre in the city, 94 MacDougal Street. When he steps out the door there, the first things greeting him are a huge Italian flag and the smell of rosemary and oregano, courtesy of the neighbours across from “America’s oldest Italian heritage organization” Tiro a Segno, the Italian culture house that has been housed at number 77 since 1927.

The most likely walking route then takes Dylan down Prince Street, past the smell of warm bread from the Italian bakery Vesuvio, which has been baking its breads and selling Italian pastries at house number 160 since 1920. We are now 600 metres, 0.4 miles from the studio and we are walking the cobblestones of Prince Street. The third street on the right is Greene Street, where Leon Russell, Carl Radle, Jesse Ed Davis and Jim Keltner have probably just finished recording the basic tracks that will become “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece” a little later.

Pure speculation, of course, but it really doesn’t sound too insane. Dylan putting on his coat, saying “see ya later” to wife and children and opening the door. It is a warm, windy day in late winter, about 18 degrees (65 °F) and dry. On the way to his appointment with Russell in the studio, things are probably already starting to bubble up. Open to inspiration, he walks along the cobblestones of the back then rather shabby part of SoHo, past the Italian flag of Tiro a Segno and bakery Vesuvio, which opens a door to a back room in his phenomenal music memory.

And there he finds the trifle “Going Back To Rome”. A forgotten song for which he most likely wrote a few lines in Rome in January 1963, which he performed only once, seemingly improvising the rest of the lyrics, judging from the only recording we know, the 8 February 1963 recording from the basement of Gerde’s Folk City in New York. It’s a somewhat giggly performance, the song sounds vaguely like a kind of precursor to “She Belongs To Me”, has the playful refrain line Well I’m going back to Rome, that’s where I was born, and a closing couplet of which we will hear a faint echo today:

You can keep Madison Square Garden Give me the Coliseum You can keep Madison Square Garden Give me the Coliseum So I want to see the gladiators Man I can always see ‘em [laughs again]

In such a scenario, the step to the streets of Rome filled with rubble, to the Spanish Stairs and to dodging lions inside the Coliseum is not that big. In any case, the transfer of the rather frenzied rhyme finding Coliseum / always see ’em (in “Masterpiece”: I could hardly stand to see ’em) does make a strong case for the likelihood of that scenario.

And with that, with that rhyme and with the streets of Rome, the song poet with a cold has his catalyst, the key to open the creative part of his brain.

———-

To be continued. Next up When I Paint My Masterpiece part 3: Blake did come up with some bold lines

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)