The series looking at volume 1 of Clinton Heylin’s epic review of Bob Dylan concluded here, and at the end of that article, you will find an index to all the articles that were part of that series. This is part two of the review of Volume 2 of Heylin’s opus., “Far Away From Myself”. Part one was Far Away From Insight

———————-

By Tony Attwood

How much of Bob Dylan’s compositions reflect himself? It is a difficult question to answer, just as people have for many years worked on lists of songs from which Dylan has lifted either lyrics, or melodies or chord sequences. If you want to get into building a list of where all the songs come from there’s quite a decent article on BobDylanplagiarisms.

Yet there are several separate issues here: the first being “does Dylan use other people’s songs?” – and the answer for that seems to be clearly yes. But another is does it matter legally? The answer there is yes, up to a point. A third question is, does the fact that some of his lyrics or melodies or chord sequences have been taken from elsewhere, actually matter morally? And on that one, you have to make your own decision.

I suspect Bob would argue that this musical borrowing is how it has always been; he’s just carrying on the tradition. Besides no one can claim the rights to a 12 bar blues. But on the other hand, some people do get a bit agitated about this: if you want to see how, try the article “Jacques Levy’s wife and publishing company seek $7.25m (£5.25m) from recent sale of Dylan’s publishing rights to Universal Music Publishing”. That piece comes from the Guardian, a British newspaper which is considered by many to be usually accurate in its reporting (by which I mean to say, it is not a popular, sensationalist newspaper).

Heylin sees Dylan’s accident as a dividing point in Dylan’s life – volume two of the “Double Life” biography is effectively Dylan post-accident and centres on such thoughts as the “fact” that he was now learning to trust someone completely, and open up on his own feelings. And Heylin also suggests that the new songs that Dylan composed at this time came to him “relatively easily”.

He also quotes occasional lines from songs “finished and fragmentary” and finds all sorts of very odd lines therein – he calls them “fragments” – and then sets about drawing conclusions from some of them. And this is where I have my next Heylin problem.

For I wonder how valid this technique is. My central argument – or perhaps better said my central discontent about volume one of this megawork, is that Heylin plucks elements from Dylan’s life (be it his reaction to an audience, his behaviour in a relationship or some lines that he wrote and then never used in a song) and then nominates some of them as being singularly significant. But it is also possible that they are only significant because Heylin nominates them as significant. There are plenty of other lines from songs, poems and conversations, that could be equally or more significant.

Does the fact that Dylan wrote the line “My woman’s got a mouth like a lighthouse on the sea” actually indicate anything beyond the fact that here is a songwriter doing what most songwriters do; writing down lines and seeing where they go? Do they really indicate what Dylan thinks? Or should we just consider this another line written because the lyrics sprung into his mind from who knows where?

Convention has it that poets (and therefore perhaps songwriters) often do write about themselves and their emotions, but there again that is just a convention introduced by people who write about songs and songwriters. There is no evidence that this is universally or even regularly true. The most likely situation is that sometimes it is true, and sometimes not. It varies across time, and from one songwriter to another.

I have always felt that when Roy Harper wrote “I hate the white man” (available on Spotify although seemingly not elsewhere on the internet), that he meant every word. But then Roy Harper has seemed to me to have a consistent view of religion, human behaviour and the world around him, and this is expressed through his songs. Personally I rather hope that when Bob wrote

Let me go through, open the door

My soul is distressed, my mind is at war

Don't hug me, don't flatter me, don't turn on the charm

I'll take a sword and hack off your arm

he was being poetic for the purpose of the imagery of the song, and not talking literally. And if that is so, then maybe he was mostly being poetic not literal through his whole career. Just as I can tell you that my novels (hardly great works of literature but some people liked them) are truly fictional, not about real people.

Now one can’t say that Bob Dylan has had a consistent view about lots of things, because his music has changed so regularly across time. But more than that, to interpret Dylan songs as having a particular meaning, does involve trying to find consistency and clarity through each song’s lyrics; which is not necessarily there.

Heylin quotes, for example, “Card Shark” which has the lines

For life is a puzzle, those who disagree are few So if you just promise to love me little girl I'll promise to love you too.

Now are we really supposed to see this as insightful, let alone profound? Or would we not be better off seeing this as just a set of lines written by a songwriter, finding his way back into songwriting after a break, knowing that he’d maybe like to find a different way of writing but as yet is not quite sure what it is.

The notion of promising love simply because the other person in the relationship has already done so (and not because one feels that deep emotional experience) is hardly worthy of much commentary, and really seems to be a fairly poor follow-on from the statement that many of us might agree with, that life is indeed a puzzle. These lines are hardly “We sit here stranded though we all do our best to deny it” which can, if we wish, give us insights into the extraordinary contradiction between our concept of “self” and of our willingness (or indeed wish) to engage with the social world beyond ourselves.

Thus when one gets to Heylin quoting “My woman’s got a mouth like a lighthouse on the sea,” one really wonders what he is trying to prove. For the point is that just as all visual artists do sketches when preparing for the moment when the big picture starts to be painted, so most poets and songwriters try out all sorts of ideas, word combinations, thoughts and anything else that pops along. The difference here is however that we don’t normally get to see the early versions.

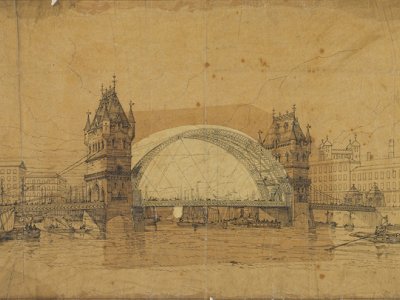

For me, the sketches by great artists in all forms of art are an interesting reminder of how most artists don’t simply create their works of art, but do quite a bit of stumbling around at first. This is true in all areas of creative works – if you want to see it in an area utterly different from songwriting just ponder this picture of an early design of Tower Bridge over the River Thames in London and the

bridge that was actually built . You might well know what it looks like now and you can see it wasn’t quite like that in the first sketch.

. You might well know what it looks like now and you can see it wasn’t quite like that in the first sketch.

So yes there is a historical interest in how things were at first, but this does not mean that the later versions grew exactly from the former.

Heylin in fact does call some of these early songs “Songwriting exercises” and quite possibly that is right, since Dylan had been away from the actual songwriting for some time before the pre-Basement work.

But if one also adds in the notion that I’ve suggested earlier, which is that most people of genius have no idea where their genius comes from or how it can be tamed and used, then really all that was going on was that Dylan was just writing his way back from the hiatus around the time of his accident.

However, Heylin is invariably clear and certain in his views of what happened how, when and why – and that’s probably what has attracted so many readers to his work. But in fact what he is doing is taking Dylan’s occasional comments about his life and work (for example as “I looked into the bleak woods and I said, ‘Something’s gotta change’.”) and then mixing simplistic statements (which we are all of us capable of making about our lives), with other later similarly simplistic outbursts, “I woke up and caught my senses, I realized I was just working for all these leeches”) which he then asserts (not tentatively suggests but utterly asserts) that these feelings link into later lyrics which Heylin then asserts were related to Albert Grossman, whose working relationship Heylin pronounces was now causing Dylan “sleepless nights”.

For me, there are two huge points here. One is, were these lines from a song sketch actually true reflections of how Dylan felt about anything? And if they were, was Dylan then actually writing about a specific person?

The answer can often be “maybe”, but without giving us any evidence into how he knows for sure, Heylin repeatedly insists that he does know. We leap from a line about a Bank Teller (“Bank Teller take to me the back room please”) to the assertion that the Bank Teller was Albert Grossman. How does Heylin know? We are not told. Where is the evidence? None is provided. What does this actually mean? We have to guess. But we are told from this that now Dylan started reading some of his older contracts to see what he had actually signed up to.

Of course this might all be true; but there is no evidence, just assertion. If Dylan did feel that he had signed a “slave contract” (as Heylin calls it) in 1961, then he would not be the first or last. That’s what people in the music business did in those days, and probably still do. If the artist turned out to be a flash-in-the-pan who was quickly forgotten by the public, the contract sat equally forgotten by both parties. If the artist reached the big time, then the agent, manager etc etc, called in his dues. That’s how it went.

Record companies and managers are not creative entities. They speak in terms of product and profit. Songwriters and performers are the ones with the feelings and emotions, and so if they do become popular they can feel they have been exploited. This is how the industry works. The managers and the companies would argue that they spend a lot of time promoting many different artists and only a few of them make money – plus they note that if the artist didn’t like the contract he shouldn’t have signed it in the first place. (As was once said, you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows).

These contracts also tend to give (or at least they did in the days before the internet) the publishers and agents control over the way the “product” (ie what the artist created) was handled. So when Heylin talks of Columbia having a “patent disregard for Dylan’s artistic integrity” he is being very slippery with reality. Record companies handling popular music of any type are there to make money for their shareholders, not to become highly regarded as the artistic curators of a living genius.

In all the discussion of such matters Heylin portrays himself as a man who could have done a much better job for Dylan than those around him at the time. He suggests that Dylan should have been advised to go on strike until Columbia implemented a previous verbal agreement. But this is all analysis with hindsight. No one knew where Dylan’s writing ability and desire to perform live would take him next. He might have stopped being prolific. Or he might have remained just as prolific but not produced works or performances that his previous audiences still wanted to hear and buy.

You can read about the handling, offers, counter offers and duplicity in Heylin’s account, and I am sure it is all true. You can also read about how some people misjudged how much would Dylan produce in subsequent years, and how popular it would be – and this is the bit I find rather silly.

For the fact was that no one knew how many new songs Dylan would produce, how much touring he would want to do, and whether his songs, recordings or tours would remain popular. Dylan was incredibly popular by 1967, but would he remain so? We know the answer through hindsight, yet somehow Heylin seems to suggest that those who didn’t have the awareness of what Dylan could continue to do, was a failing on the part of the record companies with whom he was dealing.

Thus Heylin is sketchy with his sources, but strong on assertions. Maybe everything he writes is correct – indeed that is possible, although not at all certain. But is it all significant when we come to considering Dylan’s creativity? That’s really a very different matter and one that Heylin doesn’t engage with much at all. As I said in relation to the first volume by Heylin, that’s not a subject Heylin likes to consider much.

Hear! Hear! Go on Tony!

Thank you Wouter

Clinton Heylin’s brought himself to a position of “Expert on Dylan.” He feels he’s earned this place, and he’s got the work to support that assertion, for sure. But then again, as Dylan said, “Have you done the opposite of what the experts say?” As a songwriter, poet and fiction writer myself, I know that in practice, it’s a slippery enterprise to assign personal meaning to anything authors write. There’s a difference when you’re talking about Kerouac, which isn’t fiction at all, though it’s called that, but it’s essentially biographical, non-fiction with the names changed. In Dylan’s case, the songs Sara or Ballad in Plain D can be surely seen as autobiographical, but mainly it’s pretty difficult to judge. In the first place, assuming that because the song’s narrator is “I” the narrator is the writer of the song is an incorrect premise. Who is the narrator of I Pity the Poor Immigrant? Is it Dylan? Is it God? Is it someone from Biblical Times? All of the above? In the creative process things go swirling through one’s mind, and associations might be made then put to the side. Interpretation of meaning can just be dismantling scaffolding. Tony’s point here about artist sketches is right on. I knew someone who was utterly convinced that “the sun’s not yellow, it’s chicken”, in Tombstone Blues, was actually ‘son’, as in Jesus, son of God, since John the Baptist was in the scene, until the official lyrics came out. He was highly academic, and therefore had some cache. A