Details of our most recent articles and series can be found on the home page.

by Jochen Markhorst

I Look At Barry Run

“I tried to write another Mr Tambourine Man. It’s the only song I tried to write ‘another one’.”

(Dylan, Sing Out! October 1968)

“From A Buick 6” is recorded fairly quickly, on 30 July 1965: it takes less than an hour. After two false starts, the fifth take is only the second complete performance and right away good enough for Highway 61 Revisited.

“From A Buick 6” is recorded fairly quickly, on 30 July 1965: it takes less than an hour. After two false starts, the fifth take is only the second complete performance and right away good enough for Highway 61 Revisited.

Dylan spends the remaining studio time on “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?”, which is still documented as “Look At Barry Run”, and this one doesn’t go so smoothly. The last attempt is Take 17, which accidentally ends up on the A-side of the first pressing of “Positively Fourth Street”. That intro, the first few bars… no doubt: “Like A Rolling Stone Part II”. And the rest of the song does not escape the familiarity either. Bloomfield plays a derivative of his part on that global hit, the trick whereby each verse builds tension towards the (similar) chorus, the harmonica… boy, did we hear this before.

Only Al Kooper’s tinkling on the celesta (it’s not a xylophone, as many critics think they hear) adds a particularly successful novelty to the mercurial sound. A brilliant recording, no doubt, but Dylan hears the similarities as well, and that’s a sensitive issue. He had already dropped the masterful “Farewell Angelina”, probably because it sounded too much like “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, and later he would dump the beautiful “Up To Me” as that song was too similar to “Shelter From The Storm”.

Dylan – Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window? – Take 1:

The Freudians among us might argue that Dylan had already subliminally picked up on the similarity before the recording began. We hear Dylan say, half-choking with laughter, “Look at Barry run take one” while drummer Bobby Gregg is already counting in – Look-at-Bar-ry-run has the same number of syllables, almost the same initials and exactly the same metre as Like-a-rol-ling-stone (- ‿ – ‿ -). And Uncle Sigmund would undoubtedly point out that today, 30 July, marks ten days since the release of Dylan’s greatest pride and greatest hit, which has just entered the Billboard Hot 100 (at No. 91, tomorrow it will rise sharply to No. 76). The phrase “like a rolling stone” floats just below the surface of Dylan’s stream of consciousness today.

Home-made amateur psychology that still does not explain where the particular words of the title do come from, of course. Presumably from the same wildly swirling, opaque undercurrent of consciousness that in recent months has spewed out “working titles” such as “A Long Haired Mule And A Porcupine”, “Lunatic Princess”, “Black Dally Rue” and “Alcatraz To The 9th Power” – to name but a few.

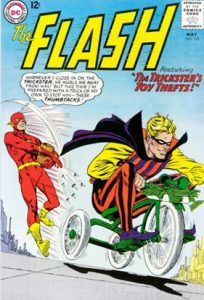

On the other hand, “Look At Barry Run” sounds far less absurd than all those other “working titles”. Even back in 1965, every teenager and young adult associated the word combination “run + Barry” with one of the most popular DC Comics heroes since 1956, Barry Allen, The Flash. Not so far-fetched when we also see the cover of the recent The Flash, the May issue (#152, “The Trickster’s Toy Thefts!”): Barry Allen, the Flash, runs after the Trickster and throws a handful of thumbtacks – with a fist full of tacks, preoccupied with his vengeance. Noteworthy: in the very first take in which we hear Dylan singing, the second take after the first false start, Dylan sings only the first line (the take is cut off after nineteen seconds):

He sits in his room, your tomb, with a mouth full of tacks

The men stop playing, we hear laughing, indistinct shouting, Dylan cheerfully says “let’s go” and “Take one again. Let’s start at the beginning. Take one, not three!” Producer Bob Johnston joins in the cheerful historical revisionism and calls out in a quasi-authoritative tone: “Hey! Take one, Look At Barry Run!” Drummer Gregg taps out the beat again, and then we hear that Dylan has reversed the possessive pronouns and changed a noun:

He sits in your room, his tomb, with his hands full of tacks

… which suggests that there may indeed be a Flash #152 lying around somewhere in the studio and Dylan is registering the running Barry with a handful of thumbtacks out of the corner of his eye. This take also quickly gets bogged down (after about 25 seconds), and then the first complete take follows, with the final opening line:

He sits in your room, his tomb, with his fist full of tacks

Well, almost final then; “his fist” will still be changed to “a fist”. In any case, it is – very unusually – the only real change in the lyrics. Atypically, Dylan will not change anything in the lyrics until the very last recording attempt, exactly four months later on 30 November – apart from insignificant details (pick up his chalk becomes hand him his chalk, when he tries becomes trying to, that sort of thing).

The arrangement does change considerably in November, which is hardly remarkable. Since Dylan’s electrification, song arrangements have changed more often than not during the recording process. Usually drastically – such as the switch from three-four to four-four time in “Like A Rolling Stone”, the halving of the tempo in “It Takes A Lot To Laugh”, the melancholicisation of “Visions Of Johanna”… and that remains Dylan’s modus operandi, as we can hear, for example, in 2023 in the colourful, fanning-out outtakes from Time Out Of Mind on The Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments – Time Out of Mind Sessions (1996–1997).

Dylan – Can You Please Crawl (single version):

However, the lyrics remain surprisingly unchanged. We are used to lyrics changing along with shifting time signatures, chord progressions, tempos and arrangements. And usually no less drastic, at that: choruses come and go, verses migrate or disappear, “you’s” become “she’s”, a blacksmith with freckles transforms into John the Baptist (“Tombstone Blues”), a ghost child becomes a brakeman (“It Takes A Lot”), and so on: a subsequent take almost always contains a textual intervention – and this peculiarity continues to characterise Dylan’s production process to this day.

This lyrical consistency in this particular song is understandable in a way; although the words are not very coherent semantically and could easily tolerate changes (such as mouth – hands – fist), the structure is technically quite perfect:

He sits in your room, his tomb, with a fist full of tacks Preoccupied with his vengeance Cursing the dead that can’t answer him back I’m sure that he has no intentions Of looking your way, unless it’s to say That he needs you to test his inventions

Rhyme master Dylan is undoubtedly pleased with rhymes such as his vengeance – intentions, with elegant, unobtrusive, waltz-like rhythms as in Preoccupied with his vengeance (– ‿ ‿ – ‿ ‿ – ‿), and all three verses adhere to the ancient, unusual rhyme scheme ababccb, known as the Lutherstrophe (because the very musical Martin Luther was so fond of it and tried to capture many psalms in that seven-line rhyme scheme). Towards the end of his life, Shelley also resorted to it occasionally (in “To Night” from 1821, for example), but there are not many more fans. Dylan undoubtedly intuitively casts his lyrics in that scheme – let’s assume that the young Beat poet did not first study Lutheran hymns.

Both with Luther and with Shelley, it creates a kind of circular feeling, a movement suggesting both completion and perpetual return, just as the varying line lengths communicate an increase and decrease, evoking a sense of ebb and flow – all wonderfully fitting with the overarching portrait that Dylan seems to want to paint here: the portrait of a lady who cannot break free from a destructive, hopeless relationship.

It is a pity, incidentally, that Dylan did not leaf through the supposed comic book. After the title story, “The Trickster’s Toy Thefts!”, in which Barry “The Flash” Allen attacks the Trickster with a fistful of tacks, there is a bonus story: “The Case of the Explosive Vegetables”. Now, what might Trickster Dylan in his mercurial years have done with that?

To be continued. Next up Can You Please Crawl part 2: The density and gravity of a Dylan song

———————

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s looking for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side A

Walt Kelly’s Pogo Possum cartoons, an influence on Dylan for sure:

(L)yndon Johnson yes

& so on the seventh day he created pogo

(Tarantula)

The John Birch Society called tbe Jack Acid Society by Kelly.