It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry (1965) part 5

by Jochen Markhorst

V He smelled like cigarettes and Dixie Peach

Don’t the brakeman look good, mama, Flagging down the “Double E”?

Robert Johnson may be untouchable, but Howlin’ Wolf comes pretty close. In the 21st century, in Theme Time Radio Hour, DJ Dylan plays a Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett song six times, and doesn’t shy away from superlatives. “This next song is entirely without flaw and meets all the supreme standards of excellence,” for example (announcement of “My Friends” in Episode 17, Friends & Neighbours). And in the decades before and since, Dylan professes his admiration just as unreservedly, in both word and deed. In “Mississippi” (2001) he quotes You know another mule is kickin’ in your stall from “Evil (Is Going On)”, “Going Down Slow” gets a subtle name-check on 2020’s Rough And Rowdy Ways (twice, in fact, both in “Key West” and in “Murder Most Foul”), as in “Caribbean Wind” (1980) for that matter, and like these, we find more whole and half reverences in Dylan’s oeuvre.

Robert Johnson may be untouchable, but Howlin’ Wolf comes pretty close. In the 21st century, in Theme Time Radio Hour, DJ Dylan plays a Chester “Howlin’ Wolf” Burnett song six times, and doesn’t shy away from superlatives. “This next song is entirely without flaw and meets all the supreme standards of excellence,” for example (announcement of “My Friends” in Episode 17, Friends & Neighbours). And in the decades before and since, Dylan professes his admiration just as unreservedly, in both word and deed. In “Mississippi” (2001) he quotes You know another mule is kickin’ in your stall from “Evil (Is Going On)”, “Going Down Slow” gets a subtle name-check on 2020’s Rough And Rowdy Ways (twice, in fact, both in “Key West” and in “Murder Most Foul”), as in “Caribbean Wind” (1980) for that matter, and like these, we find more whole and half reverences in Dylan’s oeuvre.

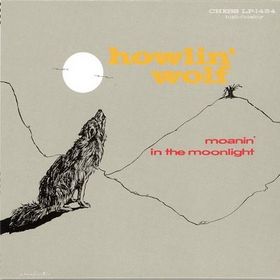

In the summer of 1965, Howlin’ Wolf is whirling in the studio air as well. We hear Mike Bloomfield, a devout fan of his fellow Chicagoan anyway, playing the lick from “Smokestack Lightning” in Take 4 of “Tombstone Blues”, and we hear another echo of the same record to which the world owes “Smokestack Lightning”, of Wolf’s unforgettable 1959 debut record Moanin’ in the Moonlight. It is a record that has often been on Dylan’s turntable, by the sound of it. Apart from “Evil (Is Going On)”, it includes classics like “I Asked for Water (She Gave Me Gasoline)” and “Forty-Four”, songs whose aftershocks we will continue to hear (in “Call Letter Blues”, for instance). And today we hear an echo of the closing track of Side A, from “All Night Boogie (All Night Long)”, from which Dylan copies the opening line Come here baby, sit down on daddy’s knee to the very first version of “Phantom Engineer”:

Don't the angel look good, babe, Sittin' on his daddy's knee?

… the middle lines of the middle verse, the ones Dylan struggles with the most. Before we get to the final Lyrics version, he tries and rejects six variations:

June 15, 1965:

Don't the angel look good, babe, Sittin' on his daddy's knee? Don't the ghost look good, mama, Sittin' on this madman’s knee? Don't the angel look good, mama, Sittin' on this madman’s knee? Don’t the ghost look good, babe, Sittin' on this madman's knee? Don't the ghost child look good, mama, Sittin' on this madman's knee?

July 29, 1965:

Don’t the brakeman look good, Being where he wants to be? Don’t the brakeman look good, Flagging down the “Double E?”

It gives a small but fascinating insight into the poetic puzzling of a creative genius at one of his mercurial high points. For this middle verse, he apparently insists on sticking to the rhythmic repetitio don’t the […] look good. The moon and the sun are fixed – although in the eight versions we know thanks to The Cutting Edge they keep swapping places. In the first version, the moon shines through the trees and the sun sets over the sea, in the next the sun shines and the moon sets, and they keep going back and forth after that (with the most awkward variation being takes 6 and 9 of 15 June: “don’t the sun look good, baby, coming down through the trees”). Anyway: the sun and moon are stayers, courtesy of Bob Wills and Leroy Carr.

But the filling in of the repetitions between the two celestials proves less steadfast. In the five variations of 15 June, when the song is still fresh and young and uptempo and booked as “Phantom Engineer Number Cloudy”, the ghost of Casey Jones still seems to be floundering around in Dylan’s stream of consciousness. “Angel”, “ghost”, and “ghost child”, featured on either the daddy’s knee borrowed from Howlin’ Wolf or the madman’s knee – these are images dripping with symbolism, evoking a machinist on his way to his death. The primal version, with the “angel” on “daddy’s knee” is then perhaps a bit too corny, a bit too cheap country sentimentality, the song poet feels. Flipping then to the other extreme: the angel is replaced by a “ghost”, daddy by a “madman”. Granted, all corniness has evaporated – but now things are getting a bit too hysterical again, the ad-libbing Dylan seems to think. And shoves the angel back onto the knees again, then again the ghost, and eventually even a “ghost child”… no, none of this works, he thinks.

He takes his time. The next take is 44 days later. And in those six weeks, Dylan seems to have made up his mind about this verse and made an academic decision: the lyrics shall be neatly balanced. In every verse a reverence to Robert Johnson, in every verse an erotic ambiguity, and what we were still missing in this verse is now also inserted: the train reference. What kind of train reference seems unimportant. Well, brakeman then. The brakeman floats on the surface of Dylan’s inner baggage anyway. He has already sung a few brakemen in recent years; in “Freight Train Blues” on his debut album, and in 1961 “Railroad Bill” is in his repertoire as well – two of many songs in which a brakeman comes along.

But given his outspoken respect and admiration for “The singing brakeman” Jimmie Rodgers, Dylan probably chooses “brakeman” rather instinctively when he wants to integrate a random train reference into a song lyric – while at the same time looking for words for “crossing the boundaries between country and blues music”. Moreover, like any folk artist, he can sing along with Rodgers’ evergreen “Waiting For A Train”, in which the brakeman is the antagonist of a hapless hobo (I walked up to a brakeman to give him a line of talk / He said if you’ve got money I’ll see that you don’t walk). Originally a B-side to 1929’s “Blue Yodel No. 4”, the B-side soon eclipsed the A-side and grew into one of the most popular country classics – the song is on a pedestal with and in the repertoire of premier league players like Jim Reeves, Johnny Cash (who opens his Jimmie Rodgers tribute show in 1962 with it), Boz Scaggs, George Harrison and Jerry Lee Lewis. And with the man who is alpha and omega of “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry”, although Dylan couldn’t have known that in 1965.

In 2020, when Robert Johnson’s stepsister Annye Anderson publishes her memoir Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson, driven by the conviction that justice is not being done to the memory of her beloved older brother, critics agree: the book written by Mrs Anderson together with music historian Preston Lauterbach sheds an as-yet-unknown, enriching light on Johnson, his life and especially his musical influences. He played anything, says Anderson, anything people wanted to hear: “I remember him asking all the guests, and even the children, ‘What’s your pleasure?’” And then he would play a Fats Waller number, or “Pennies from Heaven”, Gene Autry or Count Basie or “Sugar Blues” or Louis Armstrong… Johnson was a walking jukebox. But his sister loved country, and especially Jimmie Rodgers:

“We had that record “Waiting For A Train.” I sang that with Brother Robert all the time. […] Nothing could take the place of the trainman, Jimmie Rodgers. I learned to sing along with those Jimmie Rodgers records. I couldn’t yodel, but I’d sort of hum it. Brother Robert could really yodel. He identified with Jimmie Rodgers through the “TB Blues”—we had two older half-siblings die of TB in Memphis around the time Jimmie Rodgers passed from it.”

The memoir concludes with a marathon interview conducted by the trio of music historians Peter Guralnick, Elijah Wald, and Preston Lauterbach with Mrs Annye C. Anderson, and in it Jimmie Rodgers and “Waiting For A Train” come up again:

“He was blues, he was folk, he was country. Jimmie Rodgers was his favourite, and he became my favourite. Brother Robert could yodel just like he did. We did “Waiting for a Train” together.”

“He was blues, he was folk, he was country”… unintentionally, Mrs Anderson articulates an unmistakable, artistic kinship with Dylan. With an extra colourful touch as she recalls her last memory of her brother:

“Walking with him to Third Street, Highway 61, where he’d hitch a ride across the Harahan Bridge, going over the Mississippi River. I still think of how it felt to hug him. He put his skinny arms around me. His clothes felt starched and pressed. His face felt smooth. He smelled like cigarettes and Dixie Peach.”

To be continued. Next up It Takes A Lot Part 6: Those old Baptist hymns

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door