My Own Version Of You (2020) part 18

by Jochen Markhorst

XVIII “It is strange what people discover in my work”

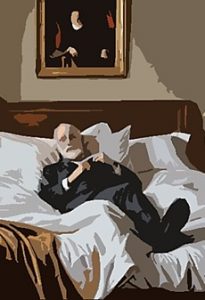

Step right into the burning hell Where some of the best known enemies of mankind dwell Mister Freud with his dreams and Mister Marx with his axe See the rawhide lash rip the skin off their backs

It  is an overused pleonasm that a Nobel Prize winning literator and wordsmith like Dylan should actually oppose, “burning hell”. Granted, in Dante’s Inferno there is more ice, snow, hail and water than fire, but apart from Dante, every representation of hell in our culture is already fiery and flaming. In any case, pleonastic or not, burning hell is a tried and tested cliché, presumably ingrained in the creative part of Dylan’s mind thanks to John Lee Hooker’s LP Burning Hell and song of the same name (recorded in 1959, but not released in Europe until 1964 – and, strangely enough, not in the USA until 1992). And further deepened by Tom Jones’ beautiful 2010 cover on his best album in decades, Praise & Blame. An album that apparently made an impression on Dylan as well;

is an overused pleonasm that a Nobel Prize winning literator and wordsmith like Dylan should actually oppose, “burning hell”. Granted, in Dante’s Inferno there is more ice, snow, hail and water than fire, but apart from Dante, every representation of hell in our culture is already fiery and flaming. In any case, pleonastic or not, burning hell is a tried and tested cliché, presumably ingrained in the creative part of Dylan’s mind thanks to John Lee Hooker’s LP Burning Hell and song of the same name (recorded in 1959, but not released in Europe until 1964 – and, strangely enough, not in the USA until 1992). And further deepened by Tom Jones’ beautiful 2010 cover on his best album in decades, Praise & Blame. An album that apparently made an impression on Dylan as well;

“The night before the 2015 Grammy Awards in Los Angeles, Bob Dylan finally accepted a long-standing invitation to be honored by MusiCares, the music industry charity who regularly organizes an eve-of-the-Grammys tribute concert. Dylan accepted the award, but only on the grounds that (a) he wouldn’t perform at the concert himself and (b) that he would be allowed personally to curate the performers and the songs from his catalog that would be sung on the night. He told the organizers that they had to secure twelve specific artists, and if they couldn’t get them then he’d have to back down. In a few days, the organizers had secured everyone—and fuck me if I didn’t have the honor of being asked to sing “What Good Am I”.”

(Sir Tom Jones – Over the Top and Back – The Autobiography, 2015)

So Tom Jones is admitted to the exclusive club of the Twelve Apostles who are chosen to spread Dylan’s Word thanks to the opening song of Praise & Blame, Jones’ cover of “What Good Am I”. And on that same Side A, Dylan also enjoyed Sir Tom’s majestic version of John Lee Hooker’s “Burning Hell”, a song that seems tailor-made for Jones, by the way:

I'm going down To the church house Get down On a bended knee Deacon Jones Pray for me Deacon Jones please pray for me

Wonder producer Ethan Johns (yes, Glyn Johns’ son) and Tom opt for a remarkable, extremely stripped-down arrangement with all the flesh ripped off; a slightly distorted guitar playing a simple lick, a bare drum, and that’s it. Lots of silence between the notes. And Tom’s monumental voice, of course. But despite this apparent bareness, it is still meatier than the original.

Burning Hell is an outlier in Hooker’s oeuvre. Just Hooker’s impressive voice and an acoustic guitar, twelve songs stripped down to the bone, including stark naked versions of classics such as “Key To The Highway”, “Baby, Please Don’t Go” and “Smokestack Lightnin’”, a few original songs and adaptations such as “I Rolled and Turned And Cried The Whole Night Long”, Hooker’s own variation on the song Dylan will later adopt as well, the old classic “Rollin’ And Tumblin’” (on Modern Times, 2006). The entire LP is a strong argument for declaring John Lee Hooker the true heir to Robert Johnson, anyway. And a step right into the burning hell, too: the record opens with “Burning Hell” and closes with the terrifying “Natchez Fire”, Hooker’s interpretation of The Natchez Dance Hall Holocaust, the horrific fire in a dance hall on a Tuesday night in 1940 that killed 209 people.

The building had one door, it was on the side The fire broke out late that night People was screamin' They couldn't get out Everybody runnin', runnin' to the door The door got jammed, nobody got out All you could hear, crying, Lord have mercy

Anyhow, it’s just a stopgap solution, that burning hell. Presumably, Dylan’s draft version said something like Freud and Marx are burning in hell, which he then wanted to turn into a distichon for technical reasons. The real fireworks, of course, come right after, in that hysterical disqualification, “some of the best known enemies of mankind,” and that accusatory finger-pointing at the unsuspecting Dr. Freud and Karl Marx, resting innocently and peacefully in their graves.

It is a passage that initially brings to mind earlier partnerings in Dylan’s songs. Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot fighting in the captain’s tower from “Desolation Row”, for example, or Verlaine and Rimbaud in “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go”. But this time Dylan gives it significantly more symbolic weight than just the metaphorical qualities of previous duos: Freud dreams, Marx has an axe, they are in hell, they are “enemies of mankind” and they are horribly flogged with a whip. Enigmatic on multiple levels. Why these two, for example. Both German-speaking intellectuals, Jewish and both died in London – a rather tenuous connection, then. Dylan himself probably doesn’t know either:

“Somewhere in the universe, those three names must have paid a price for what they represent and they’re locked together. And I can hardly explain that. Why or where or how, but those are the facts.”

(New York Times, 12 juni 2020)

… he says when interviewer Douglas Brinkley asks him about the combination of Indiana Jones, the Rolling Stones and Anne Frank in the album’s opening song, “I Contain Multitudes”, and it seems obvious that the same applies to Marx and Freud in this passage.

The second puzzling aspect is the narrator’s explicit dislike of Marx and Freud, an aversion he seems to share with Dylan himself. Dylan is not openly hostile when he talks about either of these gentlemen, but his antipathy is unmistakable. “Counterfeit philosophies have polluted all of your thoughts / Karl Marx has got ya by the throat,” he sings in 1979 (“When You Gonna Wake Up?”, Slow Train Coming). In his fictionalised autobiography Chronicles, he writes belittlingly:

“There was a book by Sigmund Freud, the king of the subconscious, called Beyond the Pleasure Principle. I was thumbing through it once when Ray came in, saw the book and said, “The top guys in that field work for ad agencies. They deal in air.” I put the book back and never picked it up again.”

… and the tone in Rome in 2001 surrounding the release of “Love And Theft” is not very respectful either. For some reason, German journalist Christoph Dallach from Der Spiegel gets a one-on-one with Dylan after the press conference. “Does it bother you,” Dallach asks, “the obsession with which your admirers analyse your songs and your statements?” Yes, it does bother Dylan a bit:

“It is strange what people discover in my work. What kind of analyses are those anyway? Freudian? Or perhaps Marxist-Freudian? I have no idea about any of this.”

Dylan’s last addition, “I have no idea about any of this,” seems the most dismissive, but paradoxically, it is actually an illustration – after all, “Freudian” implies unconscious motives and interests. Plus, the seemingly random qualification “Marxist-Freudian” is a little too specific to be thrown out there completely unprovoked. And a little too relevant. Marxist-Freudian, or “Freudo-Marxism” as it is more officially called, is admittedly a catch-all term, but it is nonetheless one of the pillars of the debate about the relationship between economics, culture and the human psyche, about how our social structures can lead to alienation and isolation, to the feeling that you are stuck on Desolation Row… All in all, it is an excellent tool for expressing the relevance of at least part of Dylan’s oeuvre.

However, none of this explains why the narrator of “My Own Version Of You” thinks he sees both men in hell, with barely concealed sadistic pleasure watching as the flesh is flogged from their backs – which, incidentally, evokes an awkward association with the flogging of Jesus – or why the narrator thinks that the rather banal symbolism of a dreaming Freud and, even more banal, of the “Marx with an axe” image should inspire my version of you. “Somewhere in the universe those names must have paid a price for what they represent and they’re locked together. And I can hardly explain that.”

To be continued. Next up My Own Version Of You part 19: The striding of the gods

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues

Some time ago, I wrote this as a first stab at understanding Dylan’s “Rough and Rowdy Ways”. I was very interested to work out how far Dylan was giving his listeners some guidelines to his creative approach. What do you think?

“In ‘My Own Version Of You’, we, as an interpretive community, had already been warned as to any systematised readings of his creative efforts, Freud and Marx being damned to the lower regions of hell. By superimposing a unified ‘already formulated’ system of interpretation on his work, we may be guilty of missing the important details, extrinsic or intrinsic to the song, which appear to be extraneous to our own perceived meaning. Dylan welcomes mystery, in the forms of contradiction and ambiguity in his songs, thereby inviting a necessary collaboration from his listeners/readers , which can be both strenuous and complicated, to resolve this. Even after what seems to be a successful reading of a song, there always remain residues of the mysterious”.

Merci Paul, thanks for sharing your thoughts – that’s a wonderful stab.

I think you have summarised succinctly and to the point what I am arguing, albeit that I seem to need many more words to do so. Still, I tend towards a somewhat more prosaic interpretation of what you classify as “residues of the mysterious” and “contradiction and ambiguity”: sound often does trump semantics. Which is not my own idea, of course, as Dylan himself has been arguing this for over sixty years now. In passing remarks in interviews (such as “it’s the sound – words don’t interfere”), or on a Nobel Prize podium (“I don’t know what it means either. But it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good”), or on stage (“I’m sick and tired of people asking what it means. It means nothing!”)… Often enough to take him a little seriously, in any case.

I think this song illustrates it well. The core indeed does seem to be: a poetic expression of the songwriting process, for which the poet finds beautiful, literary images and words. But along the way, the lyrics are peppered with empty though still nice-sounding passages such as a blast of ‘lectricity that runs at top speed and You can feel it all night you can feel it in the morn’ and Step right into the burning hell – passages that may sound pleasant, but add nothing in terms of content. Or even alienate (play the piano like St. John the Apostle?). And surrounding them are the shining pearls that bring about the Holy Trinity of Rhyme, Rhythm and Reason. While, fortunately, retaining the poetry, the mystery. All through the summers and into January. I’ll be at the Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street. Can you look in my face with your sightless eye. And above all: Can you tell me what it means to be or not to be.

Groeten uit Utrecht,

Jochen

Further thoughts: As an ‘observant’ reader of ancient texts containing mythical and religious narratives, both in poetry and prose form, Dylan has been particularly drawn to those elements which create a sense of mystery in the texts. The same case could also be made for his love of folk song and tale. One of Dylan’s reviewers, Frank Kermode commented on this in his essay ‘The Metaphor at the End of the Funnel’:

‘‘What he offers is mystery, not just opacity, a geometry of innocence which they(the readers) can flesh out. His poems have to be open, empty, inviting collusion. To write thus is to practice a very modern art, though, as Dylan is well aware, it is an art with a complicated past’

The most interesting aspect here is the idea of ‘collusion’ with his readers. Dylan has often made the claim that he doesn’t really understand the meaning of his texts, by which I take it to mean, he believes he is writing in a more associative and free manner. This may well have been the case in the past, but it is my belief that ‘Rough and Rowdy Ways’ is a conscious attempt by Dylan to define his art and the way he creates his lyrics.

As regards sound and its poetic significance, i always think of what T.S.Eliott wrote on the ‘auditory imagination’.

“What I call the ‘auditory imagination’ is the feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the conscious levels of thought and feeling, invigorating every word; sinking to the most primitive and forgotten, returning to the origin and bringing something back, seeking the beginning and the end. It works through meanings, certainly, or not without meanings in the ordinary sense, and fuses the old and obliterated and the trite, the current, and the new and surprising, the most ancient and the most civilised mentality”