by Jochen Markhorst

III I will die in thy lap

I got this graveyard woman, you know she keeps my kids

But my soulful mama, you know she keeps me hid

She's a junkyard angel and she always gives me bread

Well, if I go down dyin', you know she's

bound to put a blanket on my bed

Torn between two lovers is a thing alright in Dylan’s mercurial songs. Saint Annie and Sweet Melinda in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”; the narrator in “Visions Of Johanna” oscillates between a sensual, present Louise and an idealised, absent Johanna; in “I Want You”, an equally available chambermaid keeps him away from the Queen of Spades; Ruthie in “Stuck Inside Of Mobile” wriggles herself between him and the debutante; Baby and Queen Mary in “Just Like A Woman”… and there are quite a few more explicit and less explicit love triangles in Dylan’s Five Hundred Quicksilver Days. And “From A Buick 6” is somewhere at the beginning of it all.

Torn between two lovers is a thing alright in Dylan’s mercurial songs. Saint Annie and Sweet Melinda in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”; the narrator in “Visions Of Johanna” oscillates between a sensual, present Louise and an idealised, absent Johanna; in “I Want You”, an equally available chambermaid keeps him away from the Queen of Spades; Ruthie in “Stuck Inside Of Mobile” wriggles herself between him and the debutante; Baby and Queen Mary in “Just Like A Woman”… and there are quite a few more explicit and less explicit love triangles in Dylan’s Five Hundred Quicksilver Days. And “From A Buick 6” is somewhere at the beginning of it all.

On the previous album, it’s all a lot more monogamous. Every narrator on Bringing It All Back Home chastely focuses on one single woman, but from here on Highway 61 Revisited to the last song on Blonde On Blonde, “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”, the song in which the wandering narrator finally finds peace and quiet in the arms of the One, it is one long amorous labyrinth. Biographical interpreters like to see this, of course, as a poetic expression of Dylan’s own vacillation between Joan Baez and Sara Lownds, which is indeed a biographical fact in Dylan’s life at that time (Dylan married Sara on 22 November 1965, between “I Wanna Be Your Lover” and “Visions Of Johanna”). And then they often reveal painfully banal “discoveries” that Johanna is “actually” Baez, and Sad-Eyed Lady is “obviously” Lownds, and variations and offshoots thereof. And in that tunnel, the graveyard woman would be Sara, sitting at home with her child (and soon with Dylan’s children) and the soulful mama, the mistress, the vibrant lover – Baez, or any other random side step.

Superficial and banal. In general, biographical interpretations tend to be disillusioning, robbing works of their poetic lustre, and in the case of Dylan’s sparkling beat poetry during his Mercury Period, it is even rather insulting; it reduces the lyrics to laboriously encrypted diary entries and ignores their multidimensionality.

In this case: it is much more obvious that the adultery motif in “From A Buick 6” is triggered by the model for the song, Sleepy John Estes’ “Milk Cow Blues”. Dylan not only borrows the musical structure and part of the opening lines;

Now, asked sweet mama, let me be her kid, She says I might get buggish, like to keep it hid Well she looked at me, she begin to smile, Says, “I thought I would use you for my man a while That's, just don't let my huzzman catch you there Now, if you just don't let my huzzman catch you there.”

… but also the adultery – albeit in this case it is the woman who wants to use a man as long as her “huzzman” doesn’t catch them. Dylan does borrow some of the idiom (such as Estes’ “killing you by degrees”, which will return thirteen years later in “Where Are You Tonight?”), but Dylan’s palette has – of course – much more hallucinatory images and more colourful metaphors than Estes’.

As right away demonstrated by the opening words. Estes’ sweet mama becomes a graveyard woman in Dylan’s version – the same grim, slightly morbid imagery as in the mercurial song that Dylan will never record, as the cemetery hips and graveyard lips from “Tell Me, Momma”, the same unsettling quality as the genocide fools from “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” or the guilty undertaker from “I Want You”. Of course, a morbid fascination is already evident in Dylan’s earliest work (and still in 2020), but there it is usually “real”; the songs are about real graves, cemeteries, deaths (“Ballad For A Friend”, “Let Me Die In My Footsteps”, “Only A Hobo”).

In this phase of his artistic career, his penchant for the macabre evolves into a Baudelaire-esque stylistic characteristic; graves and graveyards are no longer mere scenery, but metaphors. Dylan’s receptiveness to this is undoubtedly influenced by the Beat Poets, through Ginsberg, Corso and especially Kerouac. Dylan sometimes borrows literally from Kerouac’s Desolation Angels (her sin is her lifelessness and the perfect image of a priest for “Desolation Row”, for example), and more often paraphrases. To name just one of many examples: the automobile graveyard from Dylan’s long “prose poem” Tarantula echoes Kerouac’s automobile cemeteries. And that discernible influence extends to a penchant for sinister imagery. The suburbs of New York full of commuters, are called cemetery cities by Kerouac (On The Road), and the stew full of bones he is given in a Mexican prison cell is graveyard stew (“Orizaba 210 Blues”, 41st Chorus).

The graveyard woman in “From A Buick 6” seems to be such a resident of Cemetery City, such a housewife in Yonkers, Claremont or Glenview, or to stay closer to Sleepy John and Memphis, Collierville, at least a housewife who does the housework and looks after the kids back home in the suburbs, while her husband is “working overtime” in the city with his soulful mama.

The qualifications are cruel and unambiguous; the lawful wife at home is dead, lifeless, the mistress in the city is soulful, full of life – well, in the opinion of the adulterous husband anyway. The description “junkyard angel” gives her a little more depth; urban, cheap, a wildly attractive, disposable slut, something like that. She “gives him bread”, which doesn’t seem to have much of a metaphorical meaning, but mainly chosen for the rhyme (with “bed”). Well, “she gives me life, I survive thanks to her,” something like that perhaps – though that would be somewhat contrived, cumbersome imagery. The specific combination of words probably bounces around in Dylan’s working memory thanks to Kerouac again, from whose oeuvre so many other combinations of words trickle into Dylan’s 1965 songs. In this particular case, from the masterpiece On The Road: “I didn’t have a dime but I went down and talked to the girl. She gave me bread” (chapter 4).

The refrain that concludes each quatrain, Well, if I go down dyin’, you know she’s bound to put a blanket on my bed, shifts the focus from beat poetry to Shakespearean imagery and folk and blues lingo. At least, the context (soulful mama, bed) forces the associations with go down dyin’ towards the petite mort, the erotic climax as suggested since Shakespeare (Much Ado About Nothing Act V, sc. 2: “I will live in thy heart, die in thy lap, and be buried in thy eyes”). The suggestion that Dylan already adopted in the previous song too, in “It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry” (Well, if I die on top of the hill), and in the song before that, “Tombstone Blues”, in which “Brother Bill on top of the hill could die happily ever after”… the age-old ambiguity repeatedly and persistently imposes itself on the creating Dylan these days.

The blanket that is rolled out, finally, we have known since the nineteenth-century evergreen “Make Me A Pallet On The Floor”, the song from which W.C. Handy distilled “Atlanta Blues”, the first song Charley Patton’s brother Sam Chatmon learned to play, the song that branched out into the jazz-, country- and blues-canon at the beginning of the twentieth century. Dylan undoubtedly prefers the Mississippi John Hurt version, the version he witnessed Mississippi John playing live 1965 in Greenwich Village’s Gaslight Café;

Mississippi John Hurt, Make me a pallet on your floor

Well make me down, make me down Right over here in the corner would be fine baby, hm Yeah, this roll-out blanket right there in Yeah, come on over baby

Again, to complete the circle, an adultery song about a man who is having an affair, tangled up in the sneaky trials and tribulations of a turbulent love triangle, hoping his lawful wife will not find out:

Don't you let my good gal catch you here She, might shoot you, might cut and scar you too No tellin' what that gal might do

… does sound like a real graveyard woman, this betrayed wife.

To be continued. Next up From A Buick 6 part 4: The Three Princes of Serendip

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues

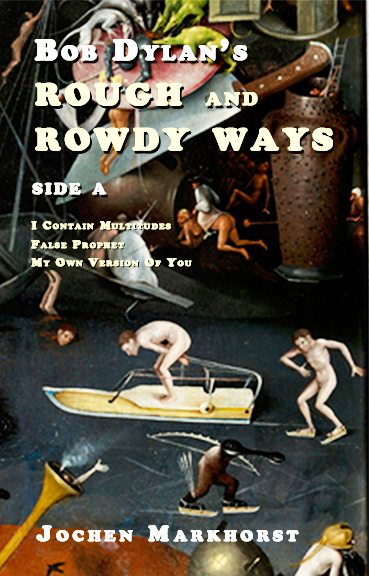

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side A