by Jochen Markhorst

“Nobody has ever captured the sound of 3 a.m. better than that album. Nobody, even Sinatra, gets it as good.” (Al Kooper)

Synesthesia is the peculiar disorder in which the holder mixes up sensory perceptions. He sees sounds, for example, hears colours or smells images. There are as many as sixty varieties, including less common ones, like connecting a flavour to a shape and experiencing specific movements at specific sounds. A more common form is called colour-graphemic synesthesia: letters or numbers are perceived as inherently coloured. Just like Dylan’s hero Rimbaud describes in his second délire from Un Saison En Enfer (1873). Colour-graphemic synesthesia, and Rimbaud connecting it to his personal definition of poetry:

I invented the colour of vowels! A black, E white, I red, O blue, U green. – I regulated the form and motion of every consonant, and, with instinctive rhythms, I flattered myself I’d created a poetic language, accessible some day to all the senses. I reserved the translation rights.

It was academic at first. I wrote of silences, nights, I expressed the inexpressible. I defined vertigos.

Supposedly, about four percent of all people have a more or less mild form of synesthesia, and with artists, especially musicians, it seems to be more common: in studies at Art Academies the percentage synesthetes fluctuates around 23%. Documented among others are Frank Zappa, Kanye West, Rimsky-Korsakov, Duke Ellington and Pharell Williams, on others there is a strong suspicion. Franz Liszt would call out to a distraught orchestra during rehearsals: “A little more blue in this passage, please!”, Rembrandt and Baudelaire are posthumously also diagnosed as synesthetes.

Science acknowledges the phenomenon only since 1866, but in the arts the mixing of sensory impressions is much older, of course. The Romantics at the end of the eighteenth century indiscriminately use colours or flavours to describe moods and sounds; for centuries heroic protagonists have felt fire flowing through their veins. And in everyday language synesthetic expressions like warm colours, bitter words or heavy footsteps have been established forever.

Dylan’s poetry is swarming with sensory blends. It’s the sixties, so at first one wonders to what extent it should be attributed to the influence of Baudelaire and Rimbaud, and/or drug use. In “Chimes Of Freedom” bolts strike shadows in the sounds, the sky cracks poems and the rain unravels tales. In “Love Minus Zero / No Limit” the beloved laughs like a flower and the wind is howling like a hammer, and in “Mr. Tambourine Man” the morning seems to be quite jingle jangle, the trees are frightened and one can hear the spinning across the sun – but then again, that’s the song in which the narrator admits: my senses have been stripped.

However, when the French symbolistes and hallucinogenic drugs have long been abandoned, the organs of perception continue to be disturbed. Not only in the songs, but also in interviews Dylan hints at synesthesia with some frequency.

The most cited interview excerpt comes from the March 1978 issue of Playboy and describes Dylan’s attempts to articulate the sound of Blonde On Blonde:

“The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album. It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up.”

Pure synesthesia. In 2001 interviewer Rosenbaum delves further into his memory and searches his notes to write a piece for The Observer on Dylan’s preoccupation with sound. And then notices that Dylan is trying to capture the sound of light:

“That ethereal twilight light, you know. It’s the sound of the street with the sunrays, the sun shining down at a particular time, on a particular type of building. A particular type of people walking on a particular type of street. It’s an outdoor sound that drifts even into open windows that you can hear (…) usually it’s the crack of dawn.”

So that is a jingle jangle morning. Still more explicit is Dylan in the ABC-TV interview in 1985, when he is asked whether he considers his song lyrics as poetry:

It’s more of a visual type thing for me: I could picture the colour of the song or the shape of it or who it is that I’m trying to appeal to in this song and what I’m trying to almost reinforce my feelings for. And I know that sounds sort of vague and abstract, but I’ve got a handle on it when I’m doing it.

Curious as well is the confession at a press conference in Rome, 2001:

Dylan: I consider colours ugly.

Q: You don’t like colours?

Dylan: Sometimes colours are okay. But when I have the choice, I prefer black & white. For my eyes that harmonizes better.

Remarkably enough, so far, but what stands out the most, when Rosenbaum rereads that interview, is the vast importance that Dylan seems to attach to capture the right sound. It seems more important, at any rate, than finding a melody or the right words (!):

I’m not just up there re-creating old blues tunes or trying to invent some surrealistic rhapsody. it’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They… they… punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose. [Pause] And all the ideas for my songs, all the influences, all come out of that. All the influences, all the feelings, all the ideas come from that. I’m not doing it to see how good I can sound, or how perfect the melody can be, or how intricate the details can be woven or how perfectly written something can be. I don’t care about those things.

And thereby Dylan downplays the endless exegesis of his lyrics. First and foremost comes the sound of the words, not so much the content. Disconnecting content and sound, or the feeling that a word evokes, is impossible, at least to a mentally healthy person. Someone with synesthesia can distinguish between reality and the synesthetic experience – seeing an orange ball at a certain sound does not have the disruptive power of a hallucination; the synesthetic knows that the orange ball is not there in reality. Likewise will a poet like Dylan not experience empty sounds in a word – he is mentally healthy, so the semantic content will always colourize the word experience. But nothing more; decisive for the choice of a word is the sound, not the content.

This knowledge helps in understanding one of Dylan’s most kaleidoscopic, impenetrable love songs, the legendary “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”. In the course of the half-century since the publication of the song, tens of thousands and tens of thousands again have ventured to an interpretation. A Google search for “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands” + “meaning” produces 65,000 hits, “+ interpretation” about as much, the Wikipedia page about Sad Eyed hits 1570 on average per month. And those are just the English-language hits. Those interpretations reveal a lot of creativity and even more despair (and remarkably often the observation that the song lasts twenty minutes – there are really only eleven minutes and twenty seconds). What are warehouse eyes, what is a geranium kiss, what are matchbook songs?

Untranslatable actually, as even the more persistent translators have to recognise. In almost every line the translator has to make a choice between sound and meaning, weighing whether the sound is more important than the image evoked by the content of the words.

Bindervoet and Henkes, tremendously creative and skilled Dutch translators of lyrics and literature altogether, dare to let go of the meaning, but then inadvertently unleash other forces. Your eyes like smoke and your prayers like rhyme becomes je ogen als rook en je gebedje gespreid. Runs like a charm, but it means something like your eyes like smoke and your warm welcoming prayer, including a laborious jeu de mots which drags the text quite a few floors down.

Musician Ernst Jansz tries it on his own and transforms that line into je ogen als rook en je gebed als een chanson (Your eyes like smoke and your prayers like a chanson). True, closer to the source. But leaving the ‘i‘-sound is a rupture, and downright awkward is the increase of number of syllables (four more), which debunks the rhythm.

The tight form in which Dylan pours his ode is a restrictive corset. We see demonstrated what Goethe meant when he said In der Beschränkung zeigt sich erst der Meister (“It is in working within limits that the master reveals himself”): framed within a strict form only a true master can create a moving work of art. For the translator that stringent form creates an extra, almost insurmountable limitation.

With your mercury mouth in the missionary times

And your eyes like smoke and your prayers like rhymes

And your silver cross, and your voice like chimes

Dylan chooses an unusual rhyme scheme and an unusual, waltz-like meter (6/8, same signature as he later uses on “Sara”), and is dazzlingly generous with literary figures of speech like internal rhyme, assonance, alliteration, anaphora, repetition and rhetorical questions, to name a few – happy trails, translator. The three rhymes of the first three lines are intertwined with the centre of this trio (like rhymes and like chimes with like smoke), the opening line alliterates three times and connects the opening mouth with respect to content to the end of the terzetto voice, the religious connotation of missionary is maintained in line two (prayers) and in line three (cross), the repetition of the opening words of the three lines, and the three metallic metaphors should be saved (mercury, silver, chimes).

Every translator already stumbles over these first lines, most of them move out of way and flee to association.

In Spain, J.M. Baule, a persistent Dylan interpreter, doesn’t praise a Distressed Looking Lady from the Lowlands, but some Sweet Lady from the Southern Countries (“Dulce Dama de las Tierras del Sur”) and turns it into a tear-jerker with hints of Canticles:

Con tu cara divina, de las diosas de los templos,

y tus ojos como miel, y tus plegarias como ruegos.

Y tu luna de oro y plata, y tu voz como un consuelo.

So this Dulce Dama has a divine face, looks like the goddesses in the temples, eyes like honey, and prayers like supplications. And a moon of gold and silver, her voice a consolation.

Very loosely translated, all in all, in which Baule allows himself an admittedly kitschy, yet somewhat dylanesque wordplay; choosing miel (honey) in line two and luna (moon) in line three, evokes to any Spaniard luna de miel: honeymoon.

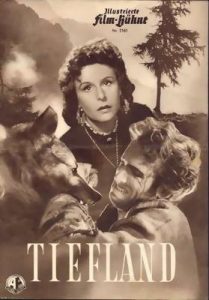

The Danish Bob Dylan, Steffen Brandt, also considers those Lowlands too far away, and turns it into a Girl from the Province of (“Pigen fra Provinsen”) and the German ladies Agnes Banes & Eva Maria Staudenmeier embark on thin ice in naming the song “Traurige Lady aus dem Tiefland”; Tiefland also happens to be the name of the last movie of nazi director Leni Riefenstahl, who summoned quite a lot concentration camp prisoners for the film (and sent them back after the shooting, most prisoners eventually died in Auschwitz).

Translation of this song is, in short, a brave undertaking, but seems to be a lost cause, and you should ask yourself: what is there to be gained? The content of the text won’t be any more understandable, it gets pushed around in all kind of directions, and you lose the sound.

The major stumbling blocks are, of course, the inimitable metaphors. Those first two already cast a language barrier by using nouns as adjectives; the poet does not call it a mercurial mouth, but a mercury mouth, like missionary times an alienating combination of two nouns. Dylan does permit himself this, this linguistic freedom, not for the first time, and this time more extreme than ever. Who among them do they think could carry you is simply incorrect. Consistent in his linguistic aberrations the poet is certainly not; in the following verses the syntax is correct again (who among them would try to impress you, for example) and he connects, very reassuring, nouns occasionally with neat adjectives. First of all Sad-eyed lady, and Spanish manners, dead angels, holy medallion, saintlike face … all of them grammatically correct and semantically understandable.

Apparently, and this confirms Dylan’s own thoughts regarding the sound, he indeed bases his word choice on this assumed synesthetic judgment. Mercury mouth is not substantively different from mercurial mouth, although it may evoke other images (‘mercury mouth’ perhaps sooner brings to mind a set of teeth with many fillings rather than ‘mercurial mouth’ does, which might summon the image of a unpredictable, clever, witty speaker), but somehow it just tastes, or sounds, or looks, or feels more correct than the linguistically logical variant.

It seems as if he started the song off as an old-fashioned blason, the medieval poetic form in which the poet in overblown terms praises the beauty of (parts of) his adored. Like some Italian poet from the thirteenth century (okay, fourteenth) does:

That frail life, that still exists in me was the clear gift of your lovely eyes, and your voice, angelically sweet. I recognise my being comes from them:

Dylan keeps hanging around the face, and gets carried away, as he admits a few years later, in a rare mood of openness to Rolling Stone‘s Jan Wenner:

“It started out as just a little thing, Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands, but I got carried away, somewhere along the line. I just sat down at a table and started writing. At the session itself. And I just got carried away with the whole thing… I just started writing and I couldn’t stop. After a period of time, I forgot what it was all about, and I started trying to get back to the beginning. (Laughs) Yeah.”

That takes place on the second day of recording in Nashville, on the night of 15 to 16 February 1966, and session musician Charlie McCoy confirms the thrust of Dylan’s memories.

When [Dylan] first came in … he asked us if we’d mind waiting a while. They had stopped at an airport in Richmond and he didn’t have a chance to finish his material. … So we all went out and let him have the studio to himself. He ended up staying in there [writing] for six hours.

Al Kooper recalls it too in his autobiography:

(…) he would sit in there for five hours without coming out and just play the piano and scribble. The atmosphere was as if clocks didn’t exist. The musicians were truly there for Bob and if it meant sitting around for five hours while he polished a lyric, there was never a complaint.

Yet all exegetes do agree about “what it all was about”: about Sara obviously. And of course, there is a lot to support that claim. First of all Dylan’s own confession in the song “Sara” (1975): “Staying up for days in the Chelsea Hotel / Writing Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands for you “.

Yet all exegetes do agree about “what it all was about”: about Sara obviously. And of course, there is a lot to support that claim. First of all Dylan’s own confession in the song “Sara” (1975): “Staying up for days in the Chelsea Hotel / Writing Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands for you “.

Furthermore, every interpreter points at the many biographical references. Sara does have ‘sad eyes’, the sheet-metal memory refers to her childhood as the daughter of a scrap dealer, she was married to a magazine-husband, the magazine photographer Hans Lownds, with whom she has a child, the child of a hoodlum and her last name Lownds reappears in Lowlands.

The isolated position of the song on the double album, physically secluded on side four, is a further hint – after three record sides filled with those girlfriends for a few hours, trollops like Sweet Marie and night-moths and women for a rainy day, Dylan eventually finds The One and honours her on her own, untainted record side, in a grande finale.

Quite convincing, so far. But not completely. The historical inaccuracy of Dylan’s claim that he wrote the song in the Chelsea Hotel, might be poetic license. But there are plenty of passages which grant particularly Joan Baez the right to feel honoured. Or, only slightly more far-fetched, the mother of Joan Baez.

Ms. Joan Chandos Baez Bridge (1913-2013) also has beautiful, sad eyes, and was actually born in the Scottish Lowlands, in Edinburgh, a daughter of a preacher man and descendant of the English Dukes of Chandos – so in Dylan’s entourage she is the only real, genuine, literal Lady of the Lowlands.

Ms. Joan Chandos Baez Bridge (1913-2013) also has beautiful, sad eyes, and was actually born in the Scottish Lowlands, in Edinburgh, a daughter of a preacher man and descendant of the English Dukes of Chandos – so in Dylan’s entourage she is the only real, genuine, literal Lady of the Lowlands.

Her daughter Joan has a much-discussed, long-term and turbulent love affair with Dylan, and is more entitled to lay claim to the musical references in the song than Sara. Like it or not, but Joan has a voice like chimes, sings prayers like rhymes (“The Lord’s Prayer” for example, 1963) and also your matchbook songs and gypsy hymns really still rather refer to a singer than to a model and ex-secretary. Baez has a Mexican father and moreover actually lived in Spain in her youth, resulting perhaps in Spanish manners, and she really lives on the coast, with the sea at your feet.

Half-time score Sara – Joan: 5-5.

The descriptions of the appearance will not score uncontroversial, decisive points. Baez’ eyes are slightly larger and hang off more; sadder than Sara. Sara’s appearance is fragile and one will rather associate hers with a face like glass, and saintlike … well, that fits both. But basement clothes suits neither ladies; both Sarah and Joan are usually reasonably fashionable and dressed for the day.

The hypnotic music accompanying the ode is highly valued, generally. From unexpected sources, too. The musician Tom Waits packs his admiration lyrically, with Biblical imagery:

For me, “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is a grand song. It is like Beowulf and it ‘takes me out to the meadow.’ This song can make you leave home, work on the railroad or marry a Gypsy. I think of a drifter around a fire with a tin cup under a bridge remembering a woman’s hair. The song is a dream, a riddle and a prayer.

Roger Waters, the leader of Pink Floyd, claims with sense of drama that the song has changed his life and encouraged him to write such long, or even longer, songs.

This length of the song has been mythologized somewhat, though. Session drummer Kenny Buttrey explains the unusual dynamics of Sad Eyed from the fact that the musicians didn’t know how long it would take, and therefore prematurely climaxed.

“If you notice that record, that thing after like the second chorus starts building and building like crazy, and everybody’s just peaking it up ’cause we thought, Man, this is it…This is gonna be the last chorus and we’ve gotta put everything into it we can. And he played another harmonica solo and went back down to another verse and the dynamics had to drop back down to a verse kind of feel…After about ten minutes of this thing we’re cracking up at each other, at what we were doing. I mean, we peaked five minutes ago. Where do we go from here?”

Great story, and it is often and gladly retold. But it’s baloney. The recording that ends up on the record, is the fourth take. On The Cutting Edge we hear two recordings more, one of them even a minute longer than the final recording, plus a practice session. Okay, it’s late at night, it’s been a long day, but it’s very unlikely that Kenny, or any of the other musicians, at the fourth take still would be surprised by the length of the song. Apart from that: the day before the men recorded among others “Visions Of Johanna”. The final take clocked 7’33” – by now the esteemed gentlemen musicians would have learned that with Dylan, you’re not there after three minutes.

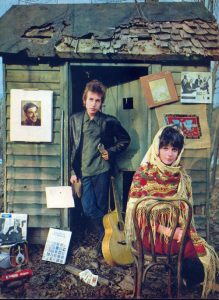

Originally, Dylan himself is passionately pleased with Sad Eyed. “This is the best song I’ve ever written,” he tells Robert Shelton, and to journalist Jules Siegel: “Just listen to that! That’s old-time religious carnival music!” Which is quite a surprising mark. By carnival he means those traveling freak shows or funfairs. In his early years, Dylan knocks up his own biography and tells journalists the most outrageous stories about his childhood. One of the stories he insists upon, with peculiar persistence, in multiple interviews, relates to his childhood at the carnival. Annually, from the age of thirteen, he travels the whole country and that is where he learns so many songs.

Originally, Dylan himself is passionately pleased with Sad Eyed. “This is the best song I’ve ever written,” he tells Robert Shelton, and to journalist Jules Siegel: “Just listen to that! That’s old-time religious carnival music!” Which is quite a surprising mark. By carnival he means those traveling freak shows or funfairs. In his early years, Dylan knocks up his own biography and tells journalists the most outrageous stories about his childhood. One of the stories he insists upon, with peculiar persistence, in multiple interviews, relates to his childhood at the carnival. Annually, from the age of thirteen, he travels the whole country and that is where he learns so many songs.

This tattle he repeats again in a radio interview in October 1961 and as an example of such a carnival song he then plays “Sally Gal”. Half a year later, another radio interviewer, Cynthia Gooding from WBAI FM Radio in New York, also wants to hear one. From his vast collection of carnival songs Dylan chooses “Standing On The Highway”. Another one, which he himself has written about an elephant lady whom he has met at the fair, is called “Won’t You Buy A Postcard” but sadly, he can not remember how the song goes.

“Standing On The Highway” now has Dylan’s name on it, but like with “Sally Gal” and Sad-Eyed, Dylan’s association with carnival songs is not comprehensible. Sally is attacked by a tramp (two thirds of the song consists of repetition of the line “I’m gonna get you girl Sally”), accompanied by a haunting, flippant guitar and ditto harmonica. Highway is a monotonous, neurotic blues with a hardly detailed reference to Death. The roving narrator is standing at some crossroads where one road leads to the tomb, he is staring at an ace of spades, and wonders in his solitude if his maiden prays for him.

True, there are some vague hints at religion and yes, some mystique hovers over the song. And elusive as “Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands” may be, it is in any case an ode to an unearthly, sublime lady with mystical qualities, the song has Biblical references (Ezekiel, especially), a symbol loaded card metaphor and some religious triggers (missionary, prayers, cross, angel, saint and holy medallion). Thin, but to Dylan apparently thick enough to ratify the song as religious carnival music.

A satisfying musical interpretation is just as impossible as a translation, evidently. There are some artists who take a swing at this relic, but almost every time it is sacrilege. Both Joan Baez (1968) and Julie Felix (Starry Eyed And Laughing, 2002), as well as Steve Howe (1999, with Yes colleague Jon Anderson) attempt to adopt the hypnotic cadence, but get stuck in silky boredom. Richie Havens is at least distinctive. He provides a funky, soulful Schwung, the bass player seems to think that he joined the Doobie Brothers and Havens’ voice is always compelling, but alas – the mystical glow of the original is completely lost (Mixed Bag II, 1974).

The only entirely satisfactory score is produced by the versatile talent Jim O’Rourke, who unleashes his productional mastery on his contribution to the tribute-CD Blonde On Blonde Revisited (2016) of the magazine Mojo. The austere interpretation (acoustic guitar and bass) with a stunning second voice in the chorus is already beautiful, but the real find is the background noise: O’Rourke has recorded the sounds of the city in the wee small hours. In the distance we hear a metro train rattling, footsteps on a wet road, passersby talking muffled, a patch of a car, a skateboard, squealing tires, horns, a police siren.

He is the only one that comes close to the synesthetic experience that Dylan manages to convey without gimmicks: catching the sound of three o’clock in the morning.

What else is on the site?

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ songs reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also now have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

‘This is the best song I’ve ever written” – Bob Dylan

Indeed it is, Bob ….I’ve always asserted that

When Joan Baez sings the song she apparently thinks it applies to Dylan; she changes the words at the beginning:

“Who do they think could bear you ….

Who could they get to ever carry you?”

Interesting article, Markhorst.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/536/Sad-Eyed-Lady-of-the-Lowlands

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.