by Jochen Markhorst

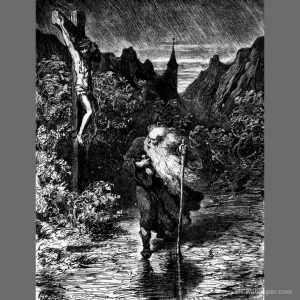

The gatekeeper of Pontius Pilate, one Cartaphilus, is a most unpleasant man. When Jesus tries to pass, at the beginning of the Stations of the Cross, this Cartaphilus strikes a nasty blow on His back and snarls that He should hurry up. “I will go,” the Lamb of God replies, “and you shall wait until I return.” With this curse He condemns the porter (a Jew, in some versions a Roman centurion) pretty much to immortality; for Jesus will not return until Judgment Day.

It is a popular, apocryphal story from the late Middle Ages and it engages literati, high clergymen and even royal circles until the twentieth century. In other versions the boor is a Jewish shoemaker from the Via Dolorosa, called Ahasverus, “the Wandering Jew”, in a French national sage he is named Isaac Laquedem, elsewhere Giovanni Buttadeo and Hans Gottschläger, but he is always a restless, Eternal Wanderer who is punished for his loose hands and disrespectful treatment of Christ. Punished with immortality, that is.

There are more stories in which immortality is presented as a terrible curse (the Flying Dutchman, for example), but even more in which immortality is desirable, or at least pleasant. It doesn’t depress the wizards and the elves in The Lord Of The Rings, for one thing. Grail Knights sacrifice years of their life to avoid mortality through the Holy Grail, Alexander the Great kept searching for the Fountain of Youth all over Asia, and even Christ Himself recruits followers with the promise of an eternal life.

This duplicity of the curse has been bothering Dylan, apparently. On the one hand it is of course an attractive mystical, archaic doom, but then doubt pinches in: is immortality really such an horreur? Dylan’s solution is macabre. The treacherous judge in “Seven Curses” will not be able to die, nor will he really live. Him awaits an eternity of maddening loneliness, much like the last days of the beetle Gregor Samsa in Kafka’s Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis): to see without being seen, to hear without being heard, to suffer without the prospect of alleviation.

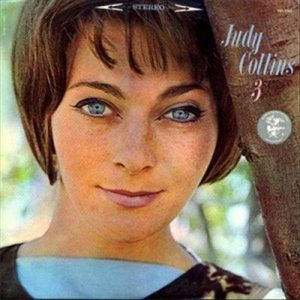

In doing so, the young poet gives his own twist to a well-known, centuries-old story. Child Ballad No. 95, “The Maid Freed From The Gallows”, Leadbelly’s “Gallows Pole”, Shakespeare’s Measure For Measure… the story of the young woman who is abused and betrayed by a conniving judge (or hangman) in a desperate attempt to save herself or a loved one from the gallows, has been told for centuries, in dozens of variations. Dylan is familiar with the version from Judy Collins, who in those early 60’s often and gladly plays “Anathea”, which in turn is an adaptation of the Hungarian “Féher Anna” (“White Anna”). According to an admiring Collins, Dylan picked up her version of the song and then did “what he has always done – he connects it with this inner, subterranean river of the subconscious.”

True, she might be expressing herself somewhat airy-fairy, but Judy does have a point here. In 1963, the 22-year-old troubadour is already a walking encyclopedia of old folk songs and he senses well what “Anathea”, with its judge “thirteen years bleeding” and his in-curability, is still missing: apart from such a mythical damnation of old-testamentarian caliber, also a psychological more exciting shift of perspective to a father, who prefers to die, rather than allowing an old pervert to touch his daughter.

The musical upgrade is at least as profound and lifts Dylans song to a level high above the Anathea’s and the Gallows Poles. Dylan renounces frills and frolics and melodic richness, and chooses a soundtrack-like approach. Almost monotonous, a bleak and sombre bass accompaniment with sparse, ghastly accents on the higher strings – it’s a sound curtain, an acoustic backdrop that enhances the sinister content of the thriller.

The effect is great and the result is an enchanting song. Unfortunately, however, it seems that the maestro himself is less content. In 1963 he plays it twice on stage (both times in New York), he records, also in New York, a stunning version for The Times They Are A-Changin’ (which eventually will surface in 1991, on The Bootleg Series) and one last time “Seven Curses” flutters down on a set list, at a relatively obscure gig in February ‘ 65 in New Brunswick, New Jersey – the bard never took the song any further than 36 miles from Greenwich Village.

One can understand that Mr. Dylan chose to reject the recording, in those days. It doesn’t, indeed, fit seamlessly between songs like “Hollis Brown” and “Hattie Carroll”. But meanwhile it has been over fifty years of not looking back on it – which surely proves an incomprehensible disinterest. The master, he works in mysterious ways.

In the meantime, the colleagues are grateful. Through the decades, dozens of covers have been recorded, and especially after the success of The Bootleg Series the song experiences a hefty revaluation. Pretty much everyone succumbs to the temptation to rig the song musically more exuberantly than Dylan did. Arrangements usually copy the Led Zeppelin-model of “Gallows Pole”, with a dramatic, ominous opening and a shift to a nervous, hectic, unnerving continuation, around the third verse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p8JQQOOcY3g

It becomes “Seven Curses” less well. After all, “Gallows Pole” doesn’t have a linear tension buildup, but rather builds on repetition until the dramatic shift when the sister offers her body. One rescuer after the other is anxiously awaited, one rescuer after the other turns out not having be able to scrounge up enough gold or silver to redeem the horse thief, and though the hangman accepts every bribe, even the sister’s soulwarming can’t save the protagonist.

Dramaturgical objections aside, such an interpretation does supply compelling covers of “Seven Curses”. The version by Solas (on For Love And Laughter, 2008) and the one by folk veteran June Tabor (in 2011, with the Oyster Band, Ragged Kingdom) are equally gorgeous. More exciting, anyway, than the ones that remain faithful to the austere inflection of Dylan, such as Andy Hill and Renee Safier on their Dylan tribute It Takes A Lot To Laugh (2001) – but that one is as well a particularly attractive, albeit a little too clean, interpretation.

You might also like Seven Curses: Bob Dylan’s feelings of legal betrayal

What else is on the site?

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ songs reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also now have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/551/Seven-Curses

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

I don’t believe Collins said she knew Dylan modified her version, rather she indicated IF he did he’d done what he always had done in terms of developing traditional material. I think it’s just as likely Dylan and or Grossman either heard the song (with Collins’ lyrics by Bert Lloyd) in London in December-January, or Grossman obtained a tape of the song which he passed on to Bob which he then reworked. We know that Dylan performed at least twice hosted by Bert Lloyd (there are photos), and that Grossman toured the folk clubs with tape recorder.