by Jochen Markhorst

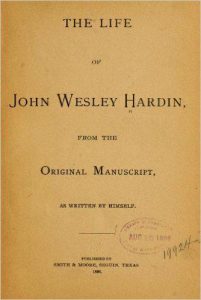

“A negro named Mage” gets his face a little scratched in a wrestling match with the 15-year-old John Wesley Hardin and does not handle it in a very mature way, as we can learn from Hardin’s posthumously published autobiography The Life Of John Wesley Hardin, “as written by himself” (1896). The next day they meet again by chance and Mage wants revenge. He threatens Hardin with “a stout stick” and says he will kill him and throw him into the creek. The teenager Hardin pulls his Colt .44, says that Mage has to go his way, but in vain. He then shoots several times, Mage goes down and dies shortly thereafter. “That was the first man I ever killed and it nearly distracted my parents.”

In the introduction, the reader is promised that the work will shed new light on the desperado, that it will show that Hardin never murdered wantonly or in cold blood and that these pages will do a certain amount of justice to his memory.

This intention fails. Hardin studied law in prison and that undoubtedly contributed to his ability to express his thoughts, but even with an academic degree he remains an aggressive, hateful and repulsive psychopath, who fails to arouse any sympathy. After that first murder, for example, more black citizens follow, because, “if there was anything that could rouse my passion it was seeing imprudent Negroes.” When he is finally locked up in Huntsville Prison, Texas, in 1878, completely unfairly of course, he counts killing 40 people. The newspaper story that he would have killed six or seven men, just because they snored, annoys him: “That only happened once.”

As may be clear, Dylan’s John Wesley Harding has little in common with Hardin (the g is a misspelling of the bard). Dylan sings of a kind of Robin Hood, helpful and honest, ‘a friend of the poor’, invents an authentic looking reference to an incident in ‘Chaynee County’ (that name does not exist) and finally paints an elusive Harding. The historic Hardin was repeatedly arrested and eventually spent 17 years behind the bars.

Dylan’s preoccupation with outlaws does intrigue. And especially his tendency to upgrade certified nutcases to well-behaved, humane role models. Jesse James gets a single, friendly name check (in “Outlaw Blues”) and in “Absolutely Sweet Marie” he plants the paradox to live outside the law, you must be honest. A first standard bearer then of that motto is John Wesley Harding. The half-beatification of Billy The Kid (1973) may be attributed to Peckinpah or the angelic aura of protagonist Kris Kristofferson, but with “Hurricane” (1975) Dylan rather breaks his neck when he passionately defends a repeatedly convicted murderer and declares him a hero. A low point reaches the singer with “Joey” (1975), the epic hymn to the immoral Mafiose killer Joey Gallo.

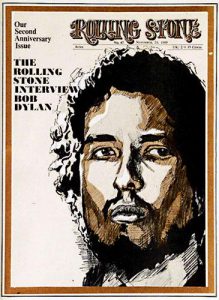

Does Dylan sense a note of unease after the release of the record? He never plays the song, neither is he very affectionate or proud when asked about it. More to the point, Dylan is derogatory. It is actually a failed start to an old-fashioned, long cowboy ballad, he reveals in 1969 to Rolling Stone’s Jann Wenner. After one and a half verses he does not feel like it anymore, but because it was “a nice little melody”, a tune he does not want to waste, the poet just writes “a quick third verse”. Records it and dum-tee-dum, Bob’s your uncle. “But it was a silly little song.”

It was also the only song that did not seem to fit on the album, Dylan continues, and that is why he places it first and calls the album after the song. That immediately makes it very important, he smiles, and otherwise people would have said it was a throwaway song. The name “John Wesley Harding”? Ah, it fits the tempo and I had it at hand.

Peculiar. It is not the only time Dylan turns away from a song of his own, but there is no song that gets this systematically destroyed by the troubadour.

At least as amazing is the sheer nonsense. The song that does not fit the album is “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”, a second outsider is “Down Along The Cove”. The title song fits seamlessly between those other riders, vagrants and desperadoes. And if it really is only about the rhythm of the syllables, the world’s best songwriter can effortlessly fit in ten alternatives. John Quincy Adams, George Edwin Butler, James Abram Garfield, John Griffith (“Jack”) London … or invent a name if necessary. Joe Franklin Dalton. In the tempo of the song and in the rhythm of the text, there are, of course, endless possibilities.

No, increased insight seems to be a more likely explanation for Dylan’s Judas kiss. In the months after the recording he is probably been made aware about the true nature of Hardin, and an ode to this extreme racist is more painful than ever in the days after the assassination of Martin Luther King (April ’68). Certainly for a renowned civil rights sympathizer such as Dylan. And presumably, his intellectual pride prevents him from admitting in the interview that he had no idea – hence the flight to transparent excuses and the exile to oblivion.

Pity, nonetheless. The song indeed does have a nice little melody and the lyrics are attractive; the same Kafkaesque clarity that leaves the mystery intact as, for example, “Drifter’s Escape”.

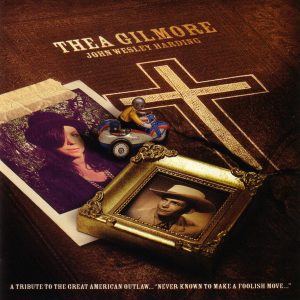

Remarkably few followers, too – apparently the colleagues have the same moral reservations as Dylan has after the recording. However, the only really serious cover is very satisfying and can be found on the brave, dazzling project of Thea Gilmore, who released an integral reinterpretation of the entire album in 2011. Her delicate, subtle, very well-kept version of the opening track elevates “John Wesley Harding” into a real overture. The first bars are bare, a sober mandolin instead of Dylan’s guitar, in the second verse organ and harmonica are added, some dry percussion and a bit later guitar, plus the muffled vocals of Thea: what a beautiful song it turns out to be to be.

You might also like

John Wesley Harding: the meaning of the music and the lyrics

Deadwood and Deadman: Bob Dylan and post-modernism

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

It’s true that outlaw killers are often romanticized in song, but your placement of Dylan’s Hurricane in that category is just plain wrong.

Jochen, in that context, you even make it sound that Hurricane was convicted of more than one murder when in fact it was his appeal of the same murder that failed.

On further appeal, Hurricane was released because the conviction was declared to be unfair. He moved to Canada and set up an organization to assist the wrongfully convicted.

Hurricane by Dylan brought the plight of boxer to the attention of the public and the press. In that respect the song does not belong with ones about John Hardin, Billy the Kid, Jesse James , or Joe Gallo at all.

Also Dylan was able to speak personally with Carter, unlike the others who be dead as a door nail.

Missourian Jesse James and Texan John Hardin were considered heroes by those supporting the Confederate cause which may help explain their getting ‘whiewashed’ in the legends of American history. Even Davy Crockett fought at the Texas Alamo in an effort to perserve slavery there.

Thanks Larry.

I sincerely hope that I didn’t give the impression as to arrogate myself an opinion on the legal settlement of murder cases. I tried to mention a dry fact: Carter was convicted twice for (the same) murder. In that respect the song is, I suppose, comparable to Dylan’s semi-beatification (almost verbatim; Carter is compared to Buddha) of other convicted murderers, like Billy the Kid and John Wesley Hardin or known killers as Joe Gallo. And probably yet another example of the songwriter’s preoccupation with murders, murder victims and murderers.

Due to my poor choice of words, I suspect; when this piece was published on a Dutch site, I received a similar, slightly indignant reaction from a reader (who, incidentally, thought that Carter was later acquitted – which is certainly not the case). I tried to be even more neutral this time, but apparently I failed again. I probably should omit the name altogether, in a next translation.

Obviously, I respect your opinion of me being plain wrong in placing Hurricane Carter in Dylan’s list of sung killers. Still – he stubbornly maintained – all those songs do sing praise of convicted murderers. Or, to put it even more accurately, men who were convicted for the crime of murder.

I doubt that Dylan cared what John Wesley Hardin was really like, any more than he did about the other outlaws he’s written or sung about, like Billy the Kidd or Pretty Boy Floyd or Joey Gallo. And doubt that he could have been disillusioned if he found out, because the song isn’t even a mythicized version of Hardin’s life ; there’s nothing in it that applies to the man at all, except perhaps the gun in every hand. I think he just liked his name–maybe the idea of an outlaw named after a great evangelist appealed to him.

I also take him at face value when he talks about the song. It IS a silly little song. It starts to tell a story, and suddenly the story is over, and it seems a bit of a cheat. Maybe Dylan was a little embarrassed about that. As you say, it actually fits the album very well. John Wesley Harding and the Basement Tapes sessions are full of stories that turn sideways, or end before they’ve begun, or don’t mean what they claim to mean, from “Clothes Line Saga” and “Tears of Rage” to “As I Went out One Morning” and “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest”–and the John Wesley Harding liner notes, which are one of his best pieces of writing and as clear a summation as one could ask of what Dylan was up to in those days. “The key is Frank.” Of course it is. But maybe with “John Wesley Harding” he thought he’d gone a little too far, made it too obvious that there was no meaning behind the meaning.

A case could be made that Dylan names the character John Wesley Harding, not Hardin, and is a hyperbolic cross-reference to John Wesley, the rebellious Methodist preacher who believes in an individualistic salvation through faith rather than through the established church; nevertheless, helping the poor ‘by good works’ was very important to Wesley – Dylan in a number of songs is critical of the hypocritical behaviour of religious leaders especially.

That is they help only themselves through the church or otherwise while giving only lip service to helping the poor.

JWH is not a heroic song, and Dylan’s dismissal of it is not to be taken at face value.

“Traveled with a gun in ‘every’ hand” is a picture of paranoia, not heroism. Likewise, a hero rarely takes a stand with his “lady by his side”, and “never known to make a foolish move” is a compliment more suited to a shyster lawyer. (“Soon the situation there was all but sorted out” is hardly a ringing endorsement of Harding’s way of dealing with a problem.)

In its 12 lines the song does an amazing job of debunking the myth of the gun-toting hero, the perfect introduction to an album that, in Dylan’s words, “deals with fear.”

Ever consider John Wesley Harding as Lee Harvey Oswald? – the album maybe not so much about LHO as the JFK Assassination in general – an unfinished concept?

1966-1967 the highest point of criticism of the Warren Comm report – Bob is reading books while recuperating – Best selling books dissent the report findings. Mark Lanes – Rush to Judgement and others questions LHO being the assassin at all.

Look at songs – As I Went Out One Morning (about the Paine award) & Drifters Escape (about a trial in the public arena) – St Augustine may have something too…”I dreamed I was among the ones who put him out to death…”.

Hurricane was not acquitted, but his convictions were set aside by the Federal Court, and no retail took place because it was felt for a number of reasons that a conviction would be unlikely.

John Hardin (no ‘g’) spent many years in prison so in no way can the song be thought of at all as being based on historical facts about the real outlaw…whether the ambiguity in the lyrics lends the song to being considered ‘heroic’ or otherwise is a matter of personal interpretation – a characteristic of many, if not most, of Dylan songs – ie, in Durango, the lady is indeed at the “hero’s” side.

As Matt says, above, the song is ambivalent at best about its protagonist. Every verse contains some sort of slippery equivocation: all but, never known, etc. Even ‘every hand’ is questionable: how many hands did he have?

Who is to say Dylan even named it after Harding? Or had any real knowledge of the real life Hardin(g)?

Either way, saying he named the album after the song because he didn’t think much of it? Come on!

As others have noted, Hurricane doesn’t fit your list.

Anyway the song is a minor classic, not a throwaway.

Typo: That of course should be ‘retrail’ in my Hurricane comment above.

This article begs for a mention of George Jackson, the Black Panther leader who was murdered in prison and memorialized in song by Dylan. Why the omission?

As a matter of fact, I did start a comparison with “George Jackson”, Raul. That song fits into a tradition: in songs like “Walls Of Red Wing” and “I Shall Be Released” the poet also plays with the notion that the world is a prison, that we are all prisoners. We see Dylan’s reflex to uplift the prisoner into a hero or a martyr in “The Ballad of Donald White”, “Drifter’s Escape” and of course in “Hurricane” and his compassion with black victims of a white, repressive system we also see in “Hattie Carroll” and “Davey Moore”.

Still, George Jackson was not convicted for murder. After a few juvenile offenses, he was actually sentenced to life imprisonment in 1961, at the age of 19, because he was behind the wheel of the escape car in a case of robbery at a petrol station (with the booty being $71).

That was the only reason I didn’t place him in a line-up with the songs mentioned in this article. But you’re right: It is definitely a fascinating subject, and Dylan’s fascination for the subject is also fascinating enough to explore further. I will.

Jochen: George Jackson was not convicted of murder; yet Hurricane’s convictions were voided as unfair and so your implication that his conviction for murder still stands seems more of justification for his inclusion in the otherwise valid grouping of song lyrics rather than it being a valid inclusion.

One might say that Hurricane was never given a chance to be found ‘not guilty’ afterwards, but who in their right mind would be so sure that they’d insist on a retrial were that even possible.

I am sure that you’re right, Larry, that placing “Hurricane” in that line-up evokes ‘implications’, and I thank you for pointing that out. It takes us on a side path which leads away from “John Wesley Harding”, true, but it is equally interesting.

Still, I really have no opinion regarding Carter’s guilt or innocence, neither did I mean to imply anything. What do I know? All I know is that he was convicted for murder – like JWH and Billy The Kid. I am, of course, familiar with the aftermath and Carter’s release, but I thought, quite incorrectly as it turns out, that this was of no importance to the general message of my article.

To some degree the unintentional implications might be due to my poor English (English is not my first language, not even my second, as you undoubtely have noticed by now). On rereading I wondered: where I wrote “Dylan rather breaks his neck when he passionately defends a repeatedly convicted murderer and declares him a hero”, I probably should have written “Dylan rather sticks out his neck…”(?). Lame excuse, I know. But still.

Thanks again Larry, and please stay this sharp.

To some degree the unintentional implications might be due to my poor English (English is not my first language, not even my second, as you undoubtely have noticed by now). Lame excuse, I know. Thanks again, and please stay this sharp.

I am sure that you’re right, Larry, that placing “Hurricane” in that line-up evokes ‘implications’, and I thank you for pointing that out. It takes us on a side path which leads away from “John Wesley Harding”, true, but it is equally interesting.

Still, I really have no opinion regarding Carter’s guilt or innocence, neither did I mean to imply anything. What do I know? All I know is that he was convicted for murder – like JWH and Billy The Kid. I am, of course, familiar with the aftermath and Carter’s release, but I thought, quite incorrectly as it turns out, that this was of no importance to the general message of my article.

To some degree the unintentional implications might be due to my poor English (English is not my first language, not even my second, as you undoubtely have noticed by now). On rereading I wondered: where I wrote “Dylan rather breaks his neck when he passionately defends a repeatedly convicted murderer and declares him a hero”, I probably should have written “Dylan rather sticks out his neck…”(?). Lame excuse, I know. But still.

Thanks again Larry, and please stay this sharp.

* some stop-and-go with my internet connection while posting that last comment. Sorry ’bout that.

All of those guys in some way were oppressed people through race, class or environment, Dylan has always been with the oppressed, plus the media always leeched and exaggerated their actions and motives, Bob knows all about leeches and exaggeraters.

I agree with Matt that Dylan’s comments about the song are misleading – in my view a silly answer to a silly question. I always viewed the song as a perfect introduction to the album, because it says so little about John Wesley Hardin. He seems to be what is seen in the eye of the beholder, he is ‘said’ to have done things (or possibly done things), and we do not know anything about the real character at all. I see it as a reflection, in part, of the unknowability of the other, and the misleading nature of what is ‘said’ to be known.

I see no reason why ‘Hurricane’ could not be included in the article if it were made clear that the boxer was considered not to have been legally convicted nor was he then tried and acquitted. ‘I know he was convicted of murder’ is a problematic assertion that goes beyond mere implication.

Dylan believed Hurricane to be innocent.

Dylan was sued over his song by a witness but the case was dismissed,

Hurricane received two honorary law degrees for his work regarding the ‘wrongfully convicted.’

However, Jochen’ I have decided that you are to be granted parole because the final court decision did not come down until long after the song was written (lol).

* (bows the heart if not the knee) *

Dylan knew he was dealing with myth, as previous commenters have said. Perhaps the spelling change alluded to Warren G. Harding, a popular president who was revealed to be corrupt after his death. There was also a controversy that he had African-American heritage, since disproved. What’s in a name? Dylan elevates and debunks his glorious protagonist.

There’s a traditional folksong called John Hardy based on a true story:

John Hardy was a desparate little man

He carried two guns every day

He shot a man on the West Virginia Line

Might have seen John Hardy getting away

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/331/John-Wesley-Harding

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

I believe this album is Dylan’s masterpiece. Yes, and that belittling answer to the silly question is a perfect misdirection. Think about it: He just accomplished the fame he had been desiring since Hibbing….and then, a near death experience…..this is the album after Blonde on Blonde. The magical mystery tour that was Blonde on Blonde. He has all the time in the world. He’s reading the bible.

I think the album needs to be taken as a whole. If you print out each song on separate sheets of paper, the format is identical. Three paragraphs each. Except of course the key. I wish it were under the door. And doesn’t he reference his materpiece in Planet Waves? Like, I already wrote it fools. Oh well…that’s what I was thinking.