I Shall Be Released (1967) by Jochen Markhorst

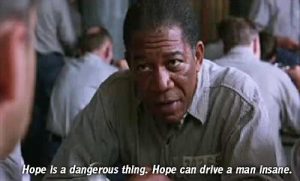

“Let me tell you something, my friend. Hope is a dangerous thing. Hope can drive a man insane.”

Despondent words with which the well-meaning Red tries to help his friend Andy Dufresne, in one of the many memorable scenes from the best film ever (according to imdb.com), The Shawshank Redemption.

Although these specific words have been devised by scriptwriter Frank Darabont, and are not to be found in the novella by Stephen King (Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, 1982), hope is the key word for the plot both in the film and in the book. Andy Dufresne survives jail and builds a future thanks to hope, Red resists for a long time, but eventually dares, hesitantly and insecure, to give in to hope and to follow a dream. Darabont rightly copies the final words literally:

I hope I can make it across the border. I hope to see my friend and shake his hand. I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams.

I hope.

Stephen King often is inspired by Dylan, quotes him in interviews and chooses song fragments as a motto, and this literary gem also seems to be inspired by a song from the bard, by the understated masterpiece “I Shall Be Released”.

On the surface anyway, because of that narrative perspective – a prisoner who stays afloat thanks to hope. And Andy’s attitude to life, get busy living or busy dying, will sound familiar to every Dylan fan. But it is the deeper layer under the plot, the level that elevates both the film, the book and the song to masterpieces.

The title of the story already reveals that this is not a classic, one-dimensional prison drama. Redemption promises a story of guilt, penance and soul liberation – and that is ultimately what it is; the story of the liberation of the man Ellis Boyd ‘Red’ Redding.

That deeper layer shares the book with Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released”. Here too, the image of a prisoner waiting for physical liberation is only the surface, hardly more than a metaphor. Dylan throws in some jargon to evoke that image (released, of course, and framed, wall and put here), but nowhere explicitly states that we hear a detainee in a penitentiary.

The choice of archaic, stately idiom as I shall and unto, and the worn gospel melody bestow on the song a much more comprehensive scope than something as anecdotal as a prison song. Here, the poet expresses the universal desire for meaning, for inner freedom, for an answer to The Supremes’ eternal question Where Do I Go From Here.

The prison metaphor is powerful and well known. One of Dylan’s forerunners, the German writer-philosopher Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), also uses it, when he wants to illustrate wherein true liberation, true salvation lies: in the release of earthly, human urges and passions.

Not essentially different from distant ancestors like Aristotle and Epicurus, or followers such as Hegel and Nietzsche, but Schiller ‘proves’ it by placing his tragic heroes in utterly physical unfreedom and allowing them to achieve inner freedom, redemption. His Maria Stuart (1800), for example, is liberated internally, experiencing salvation in her death row, the night before her execution. She sees the light, is released, and smiles at her beheading.

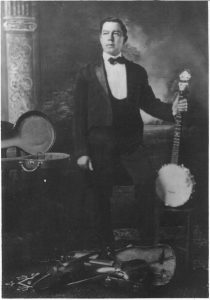

It seems  that Dylan receives immediate inspiration again from the ‘Minstrel of the Appalachians’, from the banjo-playing lawyer and folk legend Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973). His influence has been documented before with regard to “Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again”, the song with the phrase She said that all the railroad men / Just drink your blood like wine, taken from Lunsford’s classic “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground “(in which Lunsford sings ‘Cause a railroad man they’ll kill you when he can / drink your blood like wine).

that Dylan receives immediate inspiration again from the ‘Minstrel of the Appalachians’, from the banjo-playing lawyer and folk legend Bascom Lamar Lunsford (1882-1973). His influence has been documented before with regard to “Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again”, the song with the phrase She said that all the railroad men / Just drink your blood like wine, taken from Lunsford’s classic “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground “(in which Lunsford sings ‘Cause a railroad man they’ll kill you when he can / drink your blood like wine).

Dylan knows that song from the invaluable Anthology of American Folk Music, the three-part double album compilation from 1952 with eighty-four folk, country and blues songs, collected by the eccentric amateur musical anthropologist Harry Smith.

“I Wish I Was A Mole” is on Volume 3, Songs, but Dylan also listens to Volume 2, Social Music. “Rocky Road” from the Alabama Sacred Harp Singers, Elsewhere McIntorsh’ “Since I Laid My Burden Down”, “John The Revelator” by Blind Willie Johnson … it is a treasure trove of songs that echo more and less directly in Dylan’s songs. And on side 4 of this double album is that other song by Bascom Lamar Lunsford that has gotten under Dylan’s skin: “Dry Bones” (not to be confused with “Dem Bones”, the Delta Rhythm Boys hit from the 40s).

Lunsford recorded “Dry Bones” in 1928 after learning it, by his own account, in North Carolina from one Romney, a wandering black preacher. It is a powerful, simple song with a colourful, biblical text. The five short couplets browse rather haphazardly through the Holy Scriptures, as through Genesis in the first verse:

Old Enoch he lived to be three-hundred and sixty-five

When the Lord came and took him back to heaven alive

The other stanzas pick from Acts, Exodus and Ezekiel, so criss-cross from the Bible. In the third verse the Dylan fan has a second aha-experience: The Lord said: “Moses, you’s treading holy ground.” – both content-wise and stylistic the blueprint for “Highway 61 Revisited” (God said to Abraham: “Kill me a son”).

But the first really earpricking moment is the second verse and the chorus that follows it:

Paul bound in prison, them prison walls fell down

The prison keeper shouted, “Redeeming Love I’ve found.”

I saw, I saw the light from heaven

Shining all around.

I saw the light come shining.

I saw the light come down

The verse is a terse résumé of Acts 16: 25-31, which tells how Paul liberates himself from captivity through prayer that causes the prison walls to collapse. Then he stops the prison guard from committing suicide, who now sees the light and will also serve Christ. Redeeming Love I’ve found – I have found the redeeming love, and so this scriptbook connects, like Shawshank Redemption, “Dry Bones”, Mary Stuart and “I Shall Be Released” physical, external liberation to mental, inner redemption.

By the way: the original recording of Bascom Lamar Lunsford certainly has a poignant esprit, but is also very skimpy and rowdy. The superior version by The Handsome Family really makes the song shine (Singing Bones, 2003).

“I Shall Be Released” seems perfectly tailored for a prominent place on John Wesley Harding. Between those redemption-seeking wanderers, lost souls and ancient archetypes, with that archaic use of words, that Biblical undercurrent and the predominant John The Revelator sphere, the song would have overshadowed “All Along The Watchtower”. But alas, according to Cameron Crowe in the booklet accompanying Biograph (1985) the song was finished too late for inclusion on John Wesley Harding, and it was not until after that, in the Big Pink basement on Stoll Road in West Saugerties, that is was completed. Probably not true; the song was copyrighted October 9, 1967, the album recording did not start until October 17, but what the heck.

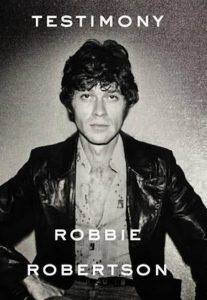

In his autobiography (Testimony, 2016) Robbie Robertson also recognises the exceptionality of the song:

A lot of the tunes coming out of the basement had deep humor, but “Tears of Rage” and “I Shall Be Released” were no joking matter. This material wasn’t meant to reflect our lifestyle or the times we were living in. It was really just about trying to write an interesting song.

It is difficult to attach too much weight to Robertson’s words; his book is rather boastful, contains errors and suspicious omissions, regularly tells self-cleaning versions of facts that are reminded differently by traveling companion Levon Helm (This Wheel’s On Fire, 1993) and reliable Dylan biographers and thus, all in all, the testimony does not seem very reliable.

About “I Shall Be Released” Robertson also notes that it is one of the most beautiful tunes Bob has written during our time in the basement, but that astute comment is a clause between two dashes. The main sentence is another pat on his own back: “After ‘I Shall Be Released’, Dylan stood up and said,” That was so good. You did it, man, you did it.” Just before that, Robbie also takes credit for one of the main pillars under the recording with which The Band will make the song public (on Music From The Big Pink, 1968).

After we laid “I Shall Be Released” down on tape, I mentioned to Richard (Manuel) that I thought he could sing that one really well. “Maybe in a falsetto, like Curtis Mayfield might do it. In the same range as your harmony.” I sang a couple lines of the chorus in falsetto, and Richard smiled. “Yeah, I can do that.”

Regardless; Robbie Robertson has been directly involved for many years, sitting right across the table, and for whole periods was 24/7 present in Dylan’s biotope, so his testimonies have historical values one way or the other. The casual observation that “I Shall Be Released” is one of Dylan’s most beautiful songs is true and is also confirmed by the endless series of obeisances. It is undoubtedly among the top 3 of Dylan’s most covered songs, is hijacked by civil rights and political activists and included in the canon early on, mainly thanks to Joan Baez.

Pretty much every cover is at least tolerable and most of them are simply attractive and moving. It is another one of those songs that can hardly be ruined, apparently. A polished approach such as that of the three-woman project Mama Cass, Mary Travers and Joni Mitchell is beautiful, but consider also the version of Bette Midler, which starts in a turbulent way and works towards an exciting, soulful climax as well.

Maroon 5 remains on the track of The Band on Amnesty album Chimes Of Freedom (2012) and is great, just like Joe Cocker (Woodstock, 1969, including Richard Manuel-like backing vocals).

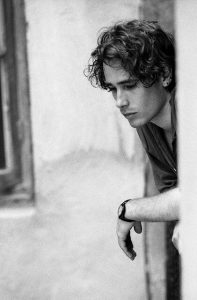

Rightfully famous is Jeff Buckley. After his death, a few recordings of the song pop up – the blood-curdling Live at Café Sin-e is one of the most successful versions of “I Shall Be Released”. Even more poignant power has a bizarre, enchanting recording of a radio broadcast, in which Buckley sings over the phone while musicians in the studio accompany him (WFMU Radio, 1992).

However, the second take of Dylan’s own embryonic basement recording, which is finally officially released in November 2014 (on The Bootleg Series Volume 11: The Basement Tapes Complete), still generates the most goose bumps. Unless, of course, a director’s cut from The Shawshank Redemption ever emerges, one where Morgan Freeman, accompanied by the harmonica his friend Andy got him, in the gloom of his dark cell, delivers a lonely rendition of “I Shall Be Released” .

Unlikely, but one can dream.

You might also enjoy

I shall be released: the meaning of the music and the lyrics

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Also: ‘I Shall Be Released’ is on the Great White Wonder bootleg of 1969, and a live version on the Passed Over And Rolling Thunder vinyl bootleg of 1978 (Providence, Rhode Island).

Hi Jochen,

understated song ? By whom ?

„I shall be released“ was in many times played by Dylan as a kind of celebrity or final song. Lyrical the song is a bit short, but thats o.k, because the impact of the song rolls directly through body and soul.

I don´t think, its useful to source down an experience of „seeing the light“ to

precedents in literature or the bible.

Some people see their light in an early lifespan, after a big struggle or some key moment. It´s nothing special, it marks a moment, where the destination of an individual life „shines“ so clear, that there is no more doubt about it, which road you want follow. Some may a personal freedom right before dying. Even it´s not too late.

Life might feel like a prison, and some people even might be responsible for the shape, you´re are in, and often it seems that no one is hearing you or have an understanding, or could help to liberate you. Except God.

„I shall be released“ stands in a row of many Dylan Songs about redemption, like „Every Grain of Sand“, „Cold Iron-Bound“ or some of the songs of his late work of „Tempest“ , even „Lucky Old Sun“ considering the way he makes this song his own.

It´s simply the fact of pain, suffering and waiting, wich is a reality for every man and woman here on earth expecting the things to come and the unkwown condition beyond the horizon or what else Dylan is trying to describe this area.

Thanks Marco,

I think we pretty much have the same feelings and opinion on the song. There seems to be some miscommunication, though; understated = ‘schlicht, unaufdringlich’. It is merely meant as a characterization of the song’s arrangement and recording.

I am not sure if I agree with your observation regarding ‘redemption’ as a frequent theme in Dylan’s songs. In “Every Grain Of Sand” e.g., I hear mainly despair and humility, though I realize that this particular song is a much debated, and often misunderstood song – probably also misunderstood by me, I might add.

I find it even harder to find ‘redemption’ in “Cold Irons Bound”. The song strikes me as a beautiful, but horribly bleak, sombre account from a protagonist who does not see a shred of light come shining – quite on the contrary.

Still, thanks for sharing your insights and the inspiration you gave: I think I’ll throw myself on “Every Grain Of Sand” next. Or “Cold Irons Bound”. Perhaps I’ll see the light and do find redemption.

Jochen, not in most of Dylan’s lyrics, you won’t! (lol )

I’ll try anyway, Larry. Next up: Wiggle Wiggle.

Thanks Jochen for giving me a reply to my thoughts,

Hope is the only thing which keeps you alive. It´s not dark yet

In my opinion his fate is going deeper and deeper.

Salvation and trying to get closer to God is on one of the central subjects he´s writing and singing about. On “Time out of mind” nearly every song is about his relationship to this unvisible power. And it goes on and on, shure you can always see a woman in the picture, but “she” isn´t written very often. It still seems to be that Covenant Woman which finally will offer salvation.

By the way, I´ve written some thoughts to your Blood on the Tracks-Article,

and like it is in these days, after 24 hours it was off the track.

Hope that this book is an inspiration for you, too.

‘To The Pines’ covered by Lansford has a blood on the tracks theme to it as you have mentioned in regards to ‘Anna Karenina’:

Her head is in the driving wheel

Her body was never found

The Jewish faith emphasizes the deliverance or release by God of his people from a place of imprisonment to the Promised Land rather than of personal salvation, ie Moses leading the Jews out of slavery in Egypt. The earth-bound Messiah is yet to come.

This lends itself to a different interpretation of ‘I Shall Be Released’ that’s full of existential angst while hoping, but still waiting, for a better future – knocking on heaven’s door and waiting for it to open in the here and now, and not in some afterlife.

In short, what is very clear is that the meaning of ‘I Shall Be Released’ is not clear at all – there being many ‘sects’ of both Jewish (beyond what I’ve mentioned above) and of Christian thought too -not to mention Gnostic formulations thereof.

That is quite a beautiful find, Larry, thanks. I did not know the origins of that song. With an unexpected extra Dylan alarm bell:

The longest train I ever did see

Was in John Brown’s coal mine

The engine had passed at half past four

The cab didn’t pass till nine

I am familiar with “In The Pines” by Leadbelly, and even more with Long John Baldry’s “Black Girl”. In both versions a gender reassignment has been performed, for some reason. Lunsfords ‘prettiest girl’ survives this time, but her husband has to pay the price:

Her husband, was a hard working man

Just about a mile from here

His head was found in a driving wheel

But his body never was found

Long John Baldry’s live-version was somewhat of an underground hit, here in Holland back in ’93 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vxc8B7XvAvE).

In any way the song, in every version, culminates in a dramatic, bloody incident on the tracks – Blood On The Tracks indeed. I was never aware of the possible connection to this song, thanks. In time to incorporate into my book, too (the “Prithee, look back, there’s blood on the track”-article you refer to is meant as the introduction).

As for the chasm between redemption and release: you’re probably right, though I suspect that the Old Testament, Exodus in particular, as well as the New Testament generally present it as a package deal. The Jews needed to be redeemed from slavery to receive the Torah on Mount Sinai, and thus be redeemed spiritually too.

If I understand it right, that is what the Jews celebrate on Pesach.

But mind you, I am far from reliable in theological questions.

Not to worry…. so are the theologians.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/279/I-Shall-Be-Released

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.