By Jochen Markhorst

Who is that lady is on the back cover of Shadows In The Night? Eventually that question is satisfactorily resolved by Dutch Dylanologist Tom Willems, in his February 2015 blog

Who is that lady is on the back cover of Shadows In The Night? Eventually that question is satisfactorily resolved by Dutch Dylanologist Tom Willems, in his February 2015 blog

It is Meg White, the ex-wife and musical ex-partner of Jack White, of The White Stripes. Jack White runs multiple bands and is an indefatigable initiator of music projects in between, shares with Dylan a profound respect for roots, especially for blues dinosaurs like Son House and Charley Patton, and honours Dylan in every incarnation with one or more covers.

We can see this, in the minimalist White Stripes with “Isis”, for example, with “One More Cup Of Coffee” and with “Outlaw Blues” and “Love Sick”. Dylan influence can also be detected outside the covers; their “As Ugly As I Seem” (from the album Get Behind Me Satan, 2005) is a carbon copy of Dylan’s “I Believe In You”.

When Meg has left him, Jack goes on with unshaken determination. Particularly striking is the collaboration with Wanda Jackson, with whom he records a steamy “Thunder On The Mountain”.

Before that he has already drawn the attention of the master himself. In 2004 Dylan plays in White’s home town Detroit and there he invites him on stage to play along with one of Jack’s most memorable songs, “Ball And Biscuit”. Undoubtedly Dylan has succumbed to the old-fashioned mix of blues with folkloric myths, and he recognizes a kindred spirit with a special talent. White is invited again and even manages to entice the old master to a scoop: in Nashville 2007 Dylan plays with him for the first time live on stage “Meet Me In The Morning” from Blood On The Tracks (’75).

A few months before that our host of Theme Time Radio Hour plays the monumental “Seven Nation Army” (episode 33, Countdown).

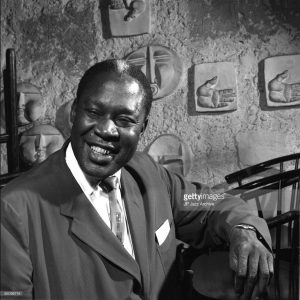

The irresistible riff of the song has been shaking the football stadiums for over a decade now and Dylan too appreciates the “two-person rhythm dynamo, Jack and Meg White,” the message coming out of their eyes, the sweat dripping out of every pore, and inspired he counts down a series of “seven things with white stripes” (a skunk, a highway, the hair of Memphis Slim …)

By then, Jack already plays in yet another band, in The Raconteurs, the support act for eight Dylan concerts in November 2006.

Without Dylan, but with a next hobby band, The Dead Weather, White tackles another blues highlight from the 70s: “New Pony”.

The attraction of that little masterpiece to White is obvious: “New Pony” is firmly rooted in the blues tradition and has on top of that the “Dylantouch”. The pony (or the horse, or the mare) as a metaphor for the female sexual partner is classic, the man usually being the rider. Dylan chooses this image as a reference to the first song of his hero Charley Patton, “Pony Blues” (1929). Recorded during the first Patton session, that also included “Down The Dirt Road”, which Dylan will place on a pedestal later, on Time Out Of Mind.

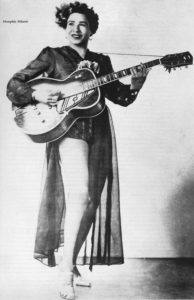

Patton’s “Pony Blues” is part of the canon by now, and the much older sexual connotation also effortlessly penetrates the blues idiom. Memphis Minnie, another idol of Dylan, milks the imagery in her “Jockey Man Blues”, the See See Rider rides his lady in the American Civil War and Big Joe Williams leaves no doubt about what he means by “My Gray Pony” (1935).

Patton’s “Pony Blues” is part of the canon by now, and the much older sexual connotation also effortlessly penetrates the blues idiom. Memphis Minnie, another idol of Dylan, milks the imagery in her “Jockey Man Blues”, the See See Rider rides his lady in the American Civil War and Big Joe Williams leaves no doubt about what he means by “My Gray Pony” (1935).

Around that time, society replaces the horse by the automobile. As does the blues: “Scarey Day Blues” from 1931 by Blind Willie McTell is probably the first. And the metaphor still holds (“Little Red Corvette” by Prince from ’82 is the best-known example), of course because the ambiguous riding can be transposed one on one. The drafty four-legged friend is now a sharp car and Memphis Minnie is not inviting a jockey, but a driver for a ride (“Me And My Driver Blues”, 1941).

There is no discussion about the sexually intended allusions in Dylan’s “New Pony”. But in fan circles the question is who the poet means by Miss X, by pony Lucifer and by the new pony. To the strength of the work it does not make any difference, of course, and remorselessly pursuing encrypted, private outpourings from the man’s personal love life is not only irrelevant but also embarrassing, but the author himself does invite rooting around. In the somewhat rudderless Rolling Stone interview with Jonathan Cott from ’78, the song is referred to fleetingly when the journalist talks about those witchy women in Dylan’s songs:

“That voodoo girl in New Pony,” Cott says, “was giving you some trouble.”

“That’s right.” Dylan replies. “By the way, the Miss X in that song is Miss X, not ‘ex’…”

It is a response to a charge that Cott does not undertake at all, so Dylan either responds to an observation made outside of this interview, or he himself is not comfortable with that translucent reference. The latter seems more likely. The singer is embroiled in a difficult separation with a lot of legal sabre-rattling and chooses in that verse for the rather bland disposition, which in addition to ‘temperament, character’ also may refer to the completion of a legal process, to a judicial decision.

The first and the second verse both sing the end of a relationship anyway. The ex-partner gets the name of the fallen angel, the end ‘hurts me more than it could ever have hurted her’ and in the second verse the protagonist is also surprised by the unpredictable behavior of the abandoned woman. It is only a small step to the separation problems with Sara, all in all.

In addition, it is rather unlikely that the world’s best songwriter does not factor in the sound similarity of ‘X’ and ‘ex’.

For the description of the new pony, Dylan draws from Arthur Crudup’s “Black Pony Blues” of (1941). “She foxtrot and pace,” sings Elvis’ musical idol of her, and “she’s got long curly hair”, and the other images and imagery (the great hind legs, the shadow on the door, the climb up on you) all come from lesser and more famous blues classics as well.

Only the mysterious voodoo verse still looks like a real Dylan original. Not so much the phenomenon of a Black Magic Woman or a Witch Queen, of course, but the enigmatic verse “I seen your feet walk by themselves”. In the world literature that expression can only be found in a novel from Machado de Assis (1839-1908), the founder of modern Brazilian literature and one of the godfathers of twentieth century South American literature. ‘Lá os meus pés andam por si,’ he writes in one of his most beautiful novels, Esau and Jacob (1904), in the English translation translated as my feet walk by themselves. Esau and Jacob visit Street Legal, the album from which “New Pony” originates, one more time (in “Where Are You Tonight?”). So who knows – maybe Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis is to be found on Dylan’s bookshelves.

However, the rhythm of the syllables will have been more decisive. “New Pony” is one of the many songs from Dylan’s catalog that bubble up from a riff and that fits seamlessly with what the master explains to Bill Flanagan in 1985: “A lot of times I’ll wake up with a certain riff, or it’ll come to me during the day. I’ll try to get that down, and then the lines will come from that.“

However, the rhythm of the syllables will have been more decisive. “New Pony” is one of the many songs from Dylan’s catalog that bubble up from a riff and that fits seamlessly with what the master explains to Bill Flanagan in 1985: “A lot of times I’ll wake up with a certain riff, or it’ll come to me during the day. I’ll try to get that down, and then the lines will come from that.“

Within the limits of riff-based, traditional blues, the Street Legal recording of “New Pony” is exceptionally rich, ingenious and colourful. Guitarist Billy Cross’ snarling guitar solo (a rare phenomenon on a Dylan album as it is) has the garage quality and filthiness from one of the better Rolling Stones records, bassist Jerry Scheff, who has played in Elvis’ band, chooses a funky accompaniment, including matching plucking accents (under Miss X, for example), the congas go as they please and the ladies’ choir does not follow the lyrics, nor the melody of the singer, but is orchestrated as a background horn section – a beautiful trouvaille.

It is a fascinating, inspired recording, and the song is still one of the highlights from the old master’s blues catalog.

Almost all covers strip the original and turn it back into a raw, ripping blues. In that category, the aforementioned approach of Jack White with The Dead Weather is the most energetic, disruptive and compelling rendition. Distinctive, however, is a lady: Maria McKee, who has enjoyed the rare privilege of Dylan giving her a song as a gift (he wrote “Go ‘Way Little Boy” for her, through the intercession of Carole Childs, 1987). She plays “New Pony” live in 2008. It opens slightly brooding, derails gradually, then silences again and thus inserts an attractive tension into the song.

However, Dylan’s original continues to tower above all covers, but he does not play it live himself – except for “Señor” and a very few exceptions, the songs from Street Legal are taboo on stage, after the year of birth 1978.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

The ‘X’ might symbolize Christ as in ‘X-mas’, and the new pony is the really the old pony ‘Lucifer’ but moreso – the morning star that symbolizes both the sex goddess Venus and the spiritually caring Jesus, not to mention the Devil, the great deceiver. Staying in the saddle, considering the disposition of such a mixed breed , would have it’s ups and downs, one would think.

I trust that clear matters up! (lol).

Nice to see this masterpiece getting some attention.

What is great about the song is what is Original, not what is Borrowed.

There is maybe two lines that could conceivably be from a pre-war sources.

Lines lines such as “she broke her leg and she needed shooting, I swear it hurt me more than it could ever have hurted her”, right at that outset, chill me to the bone. The “pony as sexual metaphor” has been ripped away from us, brutally, BANG. Despite the folksy “hurted”, and it makes you really unsure of just who this person is that’s singing, what the mental state is. Although the casualness of “she needed shooting” makes you feel this is not the first time the singer has faced this task.

The erratic mental state is reinforced by the song now swerving, digressing, speculating about a woman. That the singer can’t comprehend, can’t get in her mind.

Not just any woman: “X”, not a standard Blues name at all, but certainly a name very resonant in African-American thought and culture. Add to this the connotations mentioned in the above comment.

But at the bleeding heart of this song is the women’s refrain: “How much, how much, how much, longer?” Christ on the cross, and all of us at our moment of great suffering. “She needed shooting, I swear it I swear it hurt me more than it could ever have hurted her.”

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/445/New-Pony

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.