It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue by Jochen Markhorst

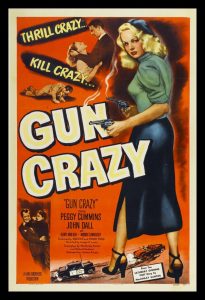

She is a terrifying femme fatale, Annie Laurie Starr in the classic film noir Gun Crazy (also released as Deadly Is The Female, 1950). When she meets the male protagonist Bart Tare, she earns a living as a sharpshooter in a traveling circus. Bart’s past we have already seen: orphan boy with an unhealthy fascination for shooting equipment, partly raised in a juvenile detention centre. By now he is a darling, though a somewhat awkward adult, just dismissed from the army as a shooting instructor. Gun crazy he is still, he can shoot like no other and he happily responds to the challenge to the public to beat Annie. On the stage there is immediately a spark. Annie falls for him once and for all when Bart defeats her a bit later. Six matches are put in a crown on Bart’s head, of which Annie manages to ignite only five. Then it’s Bart’s turn. Yonder stands your orphan with his gun. Annie puts the crown with the matches on her head, Bart is five meters away and aims. Strike another match … Bart shoots six times and, of course, all matches burn. Playing with fire, indeed: it is the beginning of a scorching love, in which Bart is dragged along on the wrong track by Annie.

She is a terrifying femme fatale, Annie Laurie Starr in the classic film noir Gun Crazy (also released as Deadly Is The Female, 1950). When she meets the male protagonist Bart Tare, she earns a living as a sharpshooter in a traveling circus. Bart’s past we have already seen: orphan boy with an unhealthy fascination for shooting equipment, partly raised in a juvenile detention centre. By now he is a darling, though a somewhat awkward adult, just dismissed from the army as a shooting instructor. Gun crazy he is still, he can shoot like no other and he happily responds to the challenge to the public to beat Annie. On the stage there is immediately a spark. Annie falls for him once and for all when Bart defeats her a bit later. Six matches are put in a crown on Bart’s head, of which Annie manages to ignite only five. Then it’s Bart’s turn. Yonder stands your orphan with his gun. Annie puts the crown with the matches on her head, Bart is five meters away and aims. Strike another match … Bart shoots six times and, of course, all matches burn. Playing with fire, indeed: it is the beginning of a scorching love, in which Bart is dragged along on the wrong track by Annie.

It ends bloody, obviously, with a dying Bart over Annie’s dead body.

With enough good will there are more images from “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” to be found in the film, but in doing so, the power of the song would be wronged; the song is certainly not an encrypted rhyme about one impression, or one event from the poet’s life. Dylan explores the terrain on which he will reach his zenith on the next two albums – clear and supple but impenetrable poetry. That self-contradicting, Rimbaud-like quality achieves the poet with a stylistic error that Jacques Derrida, the grandmaster of the deconstruction, upgrades to a style figure: the catachresis. The catachresis (literally: “wrong-use”, also abusio) connects words that are not actually connected, but are emotionally close to one another – by sound similarity for example, or by near-by association. Crying like fire in the sun seems to be a everyday metaphor, but is actually an unfamiliar combination of words. Just as deceptively familiar, a word combination like seasick sailors and expressions like the saints are coming through or gather from coincidence only seem familiar expressions.

Centuries earlier, in 1727, the admired Alexander Pope already played with catachresis in a way that could inspire Dylan: Mow the beard / Shave the grass uses the same reversal as the post office has been stolen / the mailbox is locked (from “Memphis Blues Again”) or your sheets like metal and your belt like lace (“Sad-Eyed Lady”). Dylan reads the unusual, but familiar-sounding word combinations at Rimbaud, these months. In his masterpiece Le Bateau ivre for example, where ‘distances are showering’ in a ‘green night’ under ’ember skies’.

The influence of those reading experiences, Dylan’s writing talent and his associative spirit then lead to this phase in his creation. A few half-memories of Gun Crazy, a biblical patch (Luke 9:60 “Let the dead bury their dead”), wordplay, symbol-charged metaphors, and private impressions – it works out great. Dylan’s poetry is enriched with a surreal dimension and that elevates the lyricist even higher up into the pantheon.

The clear vagueness is also irresistible in terms of content. The interpretations bounce in all directions. The most popular question is of course: who is Baby Blue? A large fraction of the experts argue for – of course – a lady, seeing the song as yet another farewell song in the vocalist’s oeuvre. Joan Baez, again. That option Dylan himself waves aside: “I have never seen Joan Baez as Baby Blue” (in the long interview with Craig McGregor, New Musical Express 1978). All too seriously we do not have to take that, because the real Baby Blue is, according to Dylan in the same interview, a character right off the haywagon, from right upstairs at the barbers shop, y’know, off the street … I have not run into her in a long time.

At least as often, the viewers see a goodbye to fellow folk artist Paul Clayton, or else David Blue. And Dylan himself is a popular candidate – saying goodbye to his folk persona. A serious minority seeks the answer not so much in a person as in an idea or in a population. Dylan bids farewell to his folk fans, for example. Al Kooper thinks so, and he is a man with a right to speak. He remembers how Dylan, after that mythical, electric performance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 at Peter Yarrow’s (from Peter, Paul and Mary) insistence, returns with his guitar to the yelling audience. Yelling, according to Kooper, because Dylan’s performance lasted only fifteen minutes, not because he had dared to play electric. And what does Dylan play when he returns? He “sang It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue to these people; banishing the acoustic-folk movement with one song right at the crossroads of its origin.”

Despite all ingenuity, erudition or experience expertise: it is more likely that the poet here, over an enchanting melody, tries to express melancholy in general, the partir, c’est mourir un peu of Edmond Haraucourt.

Many are seduced by that enchanting melody. In an (imaginary) Top 40 of most-covered Dylan songs, Baby Blue is undoubtedly among the first ten. Musically, the song is apparently at least as versatile as the lyrics; there are lovely charming, brutally aggressive, sultry jazzy, troubled psychedelic and tight rock ‘n’ roll variants of the song. Among the better known is the hit version by Van Morrison’s Them from 1966, a dreamy version, of which the raw edge in itself inspires many later covers (in that category the Chocolate Watch Band, 1968, is a winner).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62CFEEkwyIo

The rendition of Them scores remarkably high among the high priests of Dylanology; Greil Marcus loses himself again in one of his ecstatic jubilee cantatas when he writes about it (in When That Rough God Goes Riding, 2010) and Clinton Heylin even states that it “rivals the original” (in Can You Feel The Silence, 2003) .

The Byrds, on the other hand, can not really put their finger on this one; between ’65 and ’69 they try it three times, but none of the recordings pass the self-critical test of Roger McGuinn. He is right, as we can hear years later, when the recordings are released. The inevitable Manfred Mann (with his Earthband, 1972) and old hand Link Wray (on Bullshot, 1979) are memorable…

But as usual the ladies have the je ne sais quoi, That Certain Something.

In the women’s competition Bonnie Raitt delivers at least the best intro (Steal This Movie soundtrack, 2000) and Joni Mitchell colours her version mysteriously and compellingly (Night Ride Home sessions, 1991).

However, both veterans are beaten by an outsider: the actress Jill Hennessy is supported by a great band and a knowledgeable producer, and she sings remarkably well; supercooled, intense and with appropriate restraint. On the soundtrack of the NBC hit series in which she plays the leading role, Crossing Jordan (2003).

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Annie Starr it is in “Gun Crazy,” but in ‘Bronco Billy’ Eastwood says ” I’ m looking for a woman who can ride like Annie Oakley And shoot like Belle Starr.’

Bob Dylan writes:

When I met you baby

You didn’t show no visible scars

You could ride like Annie Oakley

You could shoot like Belle Starr

(Seeing The Real You At Last)

Whatever you gonna do

Please do it fast

I’m still trying to get used to

Seeing the real you at last

Dylan varies on ” It’s All Over Now”:

Take what you need you think will last

But whatever you wish to keep

You better grab it fast

Prompt association, Larry! I missed that one.

There‘s an interesting version of „It‘s all over now, baby blue“ by the (late) Austrian singer named Falco. Check it out, folks.

What would add to our understanding of the song would be to listen to the many great Dylan in Concert versions of BABY BLUE over the years. The ’66 concerts’ arrangement, the’ 88 electric version, the lovely Woodstock ’94 version, the ultra slow semi-acoustic version from Cardiff ’97 are just 4 great examples. Can you upload them to the article? I’ve seen all on YouTube except the’ 88 version. xxxJeffMan

Jeff the only live versions we have access to are the same as everyone else – anything that has been published on the internet. If you have the URL of a recording worth noting I’ll be happy to add it, but otherwise it is the case of just hoping someone somewhere has a recording and puts it up.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/319/It's-All-Over-Now,-Baby-Blue

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.