Pledging My Time (1966)

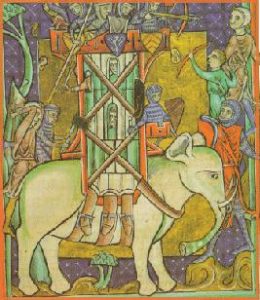

In the year 797 Charlemagne secretly sends a Frankish delegation with gifts to Baghdad, to Caliph Harun ar-Rashid, to make peace through the diplomatic way between the Arab and the Frankish Empire. Five years later, the considerably depleted delegation is back in Aachen, with a living monster, the white elephant Abul-Abbas, being the most remarkable gift. The Franks are bewildered.

But Charlemagne is perhaps even more touched by a much smaller and more graceful gift: a clepsydra, an exuberantly decorated water clock that can measure time by means of an ingenious system of tubes, taps and valves. Charles recognizes and appreciates the royal gesture of Harun: what gift is an emperor more worthy than Time itself?

Over eleven centuries later Emperor Bob can sympathize. In 1966 he is approaching the middle of the vortex, the laps are becoming shorter and go faster and faster, and he starts going under. I was in a whirlwind, he sings looking back in 1974, on the same record that tells he can not find happiness until Time Passes Slowly. Fame, money, success … all well and good, but time truly is wealth.

That realization flashes as early as November ’62, when the poet accuses his ex-love that she wasted his precious time (Don’t Think Twice), time is worth saving, he finds a year later, in The Times, in “Restless Farewell” he would like to tie up the time forcefully, with the Tambourine Man he wishes to disappear into the “foggy ruins of the time”, in “I’ll Keep It With Mine” the narrator promises to keep the time saved. In ’65, the lack of, and with it the desire for time increases, an amateur psychologist could deduce from the excessive rise in the use of the word ‘time’ in the songs as of Highway 61 Revisited. On Blonde On Blonde in as many as nine of the fourteen songs.

And explicitly the poet expresses the merits of time especially in “Pledging My Time”.

The old and familiar clichés have become hollow. In recent years, the singer has promised his heart, loyalty, letters, honesty and friendship, but now he puts the ultimate, the irrevocable on the table. He no longer promises it, no: pledging – the enamoured narrator swears an expensive oath, promises highly and holy a part of his most precious capital. This certainly must be true love. In order to avoid it becoming too soggy, the language artist packs the chorus with the pompous love speech in playful, nonsense verses. A stylistic constant in this is the antithesis. Partly these are the classic contradictions we know from the blues canon (early morning and late night, jump up and come down), others are alienating, but characteristic for the brilliance of a Dylan in shape. A splitting headache and he feels fine, the room is empty, but so stuffy that he can barely breathe and someone is lucky, but that is an accident.

It is an edgy, provocative and penetrating Chicago blues, an excellent mood changer after the previous, carnival-like splurge “Rainy Day Women # 13 & 35”, with which Blonde On Blonde opens. The song’s solid form is quickly found, The Cutting Edge learns. Nevertheless, the first take differs considerably from the final, third recording. Lyrically likewise, with three radically different verses, but especially in tempo, and thus in atmosphere.

That first take is jumpy, cheerful, echoing in the distance “Sweet Home Chicago” and the party noise of the Rainy Day Women is being extended. Irresistible, but not what Dylan means, we hear in the studio chatter afterwards: “It’s gotta have a very strong beat, you know,” and he demonstrates what he means on the piano (pa-pám, pa-pám, pa-pám). Either he is didactically gifted, or he has very clever pupils – the transformation is radical, and an instant hit; that next take, with blaring guitars and a pulsating, rushed harmonica, is on the album. Wonderful, but Dylan himself treats the song as a throw-away. It becomes a B-side, for the very successful Rainy Day Women single, and then evaporates. Just like with that other degraded masterpiece, “Queen Jane Approximately”, it takes more than two decades before the song appears on the playlist, and again the persuasiveness of the friends from Grateful Dead is needed to convince the master.

The song does not immediately know how to charm the colleagues, either. The first cover that stands out, appears in 1969. And it is not so much the musical quality of the interpretation that stands out (which is rather mediocre), but the origin: the Japanese band Apryl Fool, the band of the later electronic music legend Haruomi Hosono (from Yellow Magic Orchestra).

The Far East meets Chicago does not work – the rendition has the same displaced, alien atmosphere as Bill Murray in Lost In Translation (2003; Murray moves lost and not understanding through Tokyo, where we also hear Hosono again in the soundtrack). Despite the unimpressive musical approach, Hosono will surely have one up on Dylan. The Japanese is the grandson of Masabumi Hosono, the only Japanese passenger and survivor of the Titanic, the disaster that continues to fascinate Dylan from “Desolation Row” to “Tempest”.

Later covers can never match the original either. Duke Robilliard does it effectively, but somewhat too professional on the tribute Blues On Blonde On Blonde (2003), the horns that Luther Johnson adds are beautiful (on another tribute, Tangled Up In Blues, 1999) and the Texan Jimmy LaFave hardly ever fails – this time with a sober, acoustic reading, accompanied by an infectious Tex-Mex accordion.

The most beautiful version is performed by the eccentric guitar virtuoso Peter Parcek from Connecticut, who in 2011 on the EP Pledging My Time also excels in a heartbreaking “She Belongs To Me” and an intense “Beyond Here Lies Nothing”.

Hello there, thank you for posting this additional information regarding this track.

“The Bob Dylan Project’s goal is to present, in an accessible way, from a database, every available piece of information related to the Music of Bob Dylan.

Every Album, every Song, all the great Artists and all the Documented stories streaming on Spotify, Deezer, SoundCloud and YouTube. Over 100,000 links.

All the relevant information at the Album, Song, Artist and Document level because we link to the available source reference material from Wikipedia, the Bob Dylan website, Untold Dylan, Haiku 61, Daniel Martin, Every Song, Expecting Rain, All Dylan, Dylan Chords, Steve Hoffman, Commentaries, MusicBrainz, Positively Dylan, Second Hand Songs etc. as well as the actual music.

So when you are ready and if you are interested in accessing a comprehensive anthology on this topic, then you can find the links to all the relevant information plus Bob Dylan’s recorded versions and many other related versions inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box at: http://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/492/Pledging-My-Time

This post is designed to link the music to a broader audience…”