Jochen Markhorst

In October 2013 The Mercury News from San José reports that the building at 2066 Crist Drive, Los Altos, was granted historical monument status. The Los Altos Historical Commission has unanimously decided that the house with the attached garage from which Steve Jobs built and sold his first Apples is a historical resource and should be protected.

In October 2013 The Mercury News from San José reports that the building at 2066 Crist Drive, Los Altos, was granted historical monument status. The Los Altos Historical Commission has unanimously decided that the house with the attached garage from which Steve Jobs built and sold his first Apples is a historical resource and should be protected.

Fourteen months later, in January 2015, director Danny Boyle is granted permission to film on location for his adaptation of Walter Isaacson’s biography Steve Jobs (2011). So the film scenes that tell the embryonic phase of Apple are really set in the original garage. For that, the decor must be transformed back to 1976 and thanks to the current owner, Steve Jobs’ sister Patricia, that works out fine – Patricia was there, in those early years, and worked with co-founder Steve Wozniak and her brother on the assembly of the first hundred Apple 1 computers.

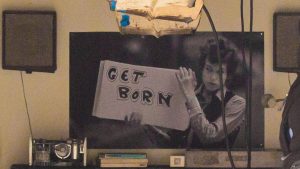

With the help of some photographs and her memory, Patricia reconstructs for the film crew the junk shop the garage was at the time. In addition, she can delight decorators with authentic attributes, like with the poster that hangs against the back wall: a still from the promotional film for “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, the iconic precursor of later video clips.

Jobs’ fanatical love for Dylan has been extensively documented and in the 2015 film Dylan is a leitmotif. In small, unobtrusive details, such as that poster against the back wall, and plainly, like in script dialogues and in playing “Shelter From The Storm” over the credits. On the soundtrack, besides Shelter, there is also “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35”, which director Boyle, contrary to expectations, plays in Jobs’ famous announcement of the Macintosh. Unexpectedly, because Jobs (wonderfully played by Michael Fassbender) opens that announcement by quoting “The Times They Are A-Changin”, preceded by a, unfortunately partly cut out, discussion with John Sculley (Jeff Daniels) about the meaning of that song. And there is another song hidden in the movie; from a radio in the background we hear “Meet Me In The Morning”.

The many Dylan references are in line with the book on which this film is based. The biography is scattered with dozens of references, Dylan records and song titles. Real Dylan love, that much is clear, and the anecdote about Jobs’ encounter with his hero is also amusing, but the most revealing piece of information is on the last page of the book, on page 570:

“You always have to keep pushing to innovate. Dylan could have sung protest songs forever and probably made a lot of money, but he didn’t. He had to move on, and when he did, by going electric in 1965, he alienated a lot of people. (…). That’s what I’ve always tried to do—keep moving. Otherwise, as Dylan says, if you’re not busy being born, you’re busy dying.”

It is more than a business motto, it is a life motto for Jobs and it also sheds extra light on that poster choice – the young Jobs daily sees Dylan’s cue card with the words get born. And, according to the script of grandmaster Aaron Sorkin, the key phrase from The Times therefore is the present now will later be past.

“This verse means that you must permanently, deliberately, rid yourself of the past, because otherwise it will also become your present,” says Jobs’ mentor Sculley. “Yes! Exactly! That’s exactly – you’re the only one … God … that’s what I mean!” the enthusiastic computer nerd yells.

It is an aphorism that will remain a guideline for the restless innovator Jobs.

The busy being born quote from “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” is one of the cast-iron, indestructible verse fragments from one of Dylan’s greatest masterpieces and one of the four lines that enters into the Columbia Dictionary of Quotations, between Shakespeare, John F. Kennedy and Mark Twain. Presidential candidate Jimmy Carter cites it in his acceptance speech at the Democratic Convention in 1976 to illustrate his progress dreams and future vision, in 2000 presidential candidate Al Gore calls it his favorite quote, in the twenty-first century writers of management books, publishing scientists, journalists and bumper sticker producers use the slogan. He not busy being born is busy dying has penetrated the collective cultural baggage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OtNZm9KXm8w

Perhaps the one-liner originates from Blind Willie McTells “You Was Born To Die” (1933), perhaps his own ’stead of learnin’ to live they are learnin’ to die (from “Let Me Die In My Footsteps”, 1962) floats around – Dylan himself does not know where this line comes from, nor the genesis of the entire song, for that matter. Already at the time of conception, in 1964, he says that his way of songwriting has changed, but reiterating is the word unconscious, a word he already uses in relation to early songs like “Girl From The North Country” and that he still chooses when he is asked for reflection on Blonde On Blonde. In the 70s he lost that talent, he says in several interviews, and he has to “consciously do what I had been able to do naturally”.

Maybe not that exceptional. The fact that Dylan is able to produce such a masterpiece as “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” so young, at the age of twenty-three, seems unimaginable, but is a characteristic of genius artists. Goethe writes his Werther when he is twenty-four, Picasso is twenty-five when he invents Cubism with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Michelangelo sculpts his David when he is twenty-five, the same age Gershwin has when he composes the Rhapsody In Blue, Hergé starts the Tintin series when he is twenty-two, Rimbaud is barely nineteen (!) when Un Saison En Enfer is published.

Still, on an instinctive level it is astonishing, and the old bard himself, in the twenty-first century, looks back with awe at this very work of his young self:

“It’s hard to live up to that kind of thing. You can’t try to top it – that’s not the point. Lyrically you can’t top it, no. I still can play that song, and I know what it can do. That song was written with a hunger that can break down stone walls. That was the motivation.”

And a month later, November 2004 in a Rolling Stone interview, he also remembers, without being asked “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)”:

“All those early songs were almost magically written. Ah… ‘Darkness at the break of noon, shadows even the silver spoon, a handmade blade, the child’s balloon…’

Well, try to sit down and write something like that. There’s a magic to that, and it’s not Siegfried and Roy kind of magic, you know? It’s a different kind of a penetrating magic. And, you know, I did it. I did it at one time.”

Magic is suiting indeed. Overwhelming is perhaps a better qualification. The singer rattles down a rhythmic barrage of 667 words over a very basic melody and a harsh chord scheme. The poet limits himself to an extremely tight rhyme scheme: each verse is AAAAAB, the B returns at the end of the next two verses and at the end of the chorus. In between, the rhyme master profusely sprinkles dizzying alliterations, internal rhymes and assonances, one-liners with the power of an aphorism and an abundance of what the Nobel Prize Committee years later would honour as “his pictorial way of thinking”.

An overwhelming thing here is that the poet never falls into the trap of empty doggerel. As far as the content is concerned, it is compelling, monumental, too. Art with a capital A, just like “Chimes Of Freedom” or “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: an eclectic collage of breathtaking images. But unlike in those works, all those images do not sketch one, many-layered panorama here. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” is the mosaic of a human condition. The listener is carried along the Great Themes, past existential fear, loneliness, religion and commerce, morality and hypocrisy, the everyday humdrum and common non-freedom. Wrapped in timeless wordings and majestic metaphors; the song is no less topical, sharp and effective fifty years later.

Strangely enough, Dylan does at first not seem to realize that he once again has managed to craft a song in the hors catégorie. The song is almost instantly there; on The Cutting Edge there is a short, interrupted take (we hear producer Tom Wilson after the first verse, after twenty-five seconds, aborting the recording because Dylan apparently is too close to the microphone). That first run is not set in very lovingly. Tom Wilson announces “Gates Of Eden”, but Dylan protests: “I wanna do this other one first.” The intro is much shorter than in the next, definitive take and sounds like “Blowin ‘In The Wind”. When it is aborted, the singer seems to lose interest: I really do not feel like doing the song and I have to do it, though. It’s such a long song. Wilson laughs. “Suit yourself, I’m with you.”

But Dylan proceeds anyway. Fortunately.

Thin ice, to the colleagues who risk a cover. Such a long song, so little melody on a rather scant chord scheme and the brilliant execution by the master himself – it requires quite some confidence to think that there is room for improvement.

They fail, obviously. Attempts enough, though. The best known is Roger McGuinn’s contribution to Easy Rider (1969).

Identical arrangement, but technically better performed harmonica and guitar playing, coming close to the excitement that the original can unleash – but it then lacks the raw purity of it.

The Swiss-born Sophie Hunger has a beautiful “One Too Many Mornings” on her repertoire and overstretches with “It’s Alright, Ma” on the live album The Rules Of Fire. However, a YouTube version of the same Frau Hunger fares better.

Plus points for the very creative, three-part rendition and powerful recital of the third part, minus points for the somewhat painful fact that Sophie occasionally runs out of breath (and her accent is a little distracting).

A bit unreal is Al ‘Year Of The Cat’ Stewart, live in 1970. His affected, through and through British accent gives an unintended comical but charming twist to the song.

Even more improbable is the slightly sultry, funky swinging version, with violins, horns and all, by Billy Preston from 1973 (Everybody Likes Some Kind Of Music) – a cover with quite a few fans, who often put it down as a guilty pleasure.

Dylan veteran Barb Jungr (Hard Rain, 2014) produces a rather schizophrenic cover; beautifully set to music (splendid organ), annoyingly articulated sung couplets, goosebumping choruses – she can sing, after all.

From an artistic point of view the most interesting interpretation is delivered by the colourful, eccentric New Yorker Franz Nicolay.

The author of the “season’s best travel book” (2016, New York Times on The Humorless Ladies Of Border Control) is infectiously crazy and provides a respectful, tumultuous mix of polka, punk and parody for the successful tribute project Subterranean Homesick Blues: A Tribute To Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home (2010). Above all, Nicolays cover reeks of anarchy – and that should please both Steve Jobs and Bob Dylan.

It’s alright ma: the masterpiece of the era

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Great piece. I comment here maybe once out of every 50 pieces I read. But as one who scribbles a bit now and then himself, I know a pat on the back from a reader helps me feel that I’m getting across. You get across. Not only in this one. It just felt like time for me to say thanks for all of them. Please keep on keeping on. You are doing it right.

Thanks Manor. That is a very kind pat on the back, and appreciated.

Hi Tony, I’m working my way through site. Great stuff! If you are looking for a good instrumental of It’s Alright Ma. Check out Charles Ballantine’s version on his Dylan cover album. Excellent music. It is not all instrumental.

Hello there, Thank you for posting this analysis of a song from Bob Dylan’s Music Box: http://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/320/Its-Alright-Ma-Im-Only-BleedingCome and join us inside and listen to every song composed, recorded or performed by Bob Dylan, plus all the great covers streaming on YouTube, Spotify, Deezer and SoundCloud plus so much more… including this link.