Jochen Markhorst

“Everything Is Broken,” says Sam Shepard in an interview with Village Voice in 1992, “that’s a great song.”

“Everything Is Broken,” says Sam Shepard in an interview with Village Voice in 1992, “that’s a great song.”

When Shepard dies in 2017, the media commemorate the talented playwright, acclaimed screenwriter and celebrated actor, but in Dylan circles the passing of the writer of the beautiful Rolling Thunder Logbook is mourned: the co-writer of Renaldo & Clara and the co-author of one of the best Dylan songs from the 80s, “Brownsville Girl”.

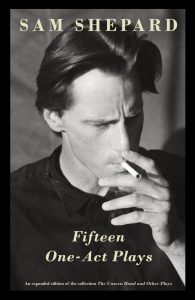

There are more Dylan-Shepard connections, and the most intriguing is Shepard’s article True Dylan, published in Esquire in July 1987. Set up as an interview, but designed by the author as a one-act play, as he has it reprinted in his collection Fifteen One-Act Plays with a new title (‘Short Life Of Trouble’).

It is perhaps the best interview ever published on Dylan. Not so much in terms of content (what Dylan tells about his love for Hank Williams, polka music in Duluth, Woody Guthrie in the hospital … we all know that, from Chronicles, from previous interviews, from biographies). But Shepard’s piece is irresistible especially because of the portrait that the brilliant playwright paints here.

We are at Dylan’s home, the bard seems completely at ease, is completely himself, he conducts telephone conversations with daughter Maria within earshot, and the playwright has the talent, the eye and the ear to make the reader almost physically present.

About the weeks after the famous motorcycle accident in ’66, for example, we have read and heard enough, but not in these terms:

“Spent a week in the hospital, then they moved me to this doctor’s house in town. In his attic. Had a bed up there in the attic with a window looking’ out. Sarah stayed there with me. I just remember how bad I wanted to see my kids. I started thinking’ about the short life of trouble. How short life is. I’d just lay there listening’ to birds chirping. Kids playing in the neighbour’s yard or rain falling by the window. I realized how much I’d missed. Then I’d hear the fire engine roar, and I could feel the steady thrust of death that had been constantly looking over its should at me. (Pause) Then I’d just go back to sleep.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FoqMxGnQY8I

It is likely that Shepard has manipulated the text of the interview. In the piece he even gets permission, in so many words, to invent whatever he wants. The final product is too beautiful, too ’round’, too composed to be a credible, truthful representation of the conversation, but perhaps therefore all the more revealing. The leitmotif of the dialogue is damaged, just as it is the theme of Shepard’s stage work and film scripts, as we also know from one of his Great Masterpieces, the script for Paris, Texas (1984). So there is a certain consistency in Shepard’s choice of “Everything Is Broken” as an example of a great Dylan song.

Dylan himself spends quite a lot of time on the words on “Everything Is Broken” in his autobiography Chronicles and the context suggests that this song indeed expresses a personal mentality of the poet. It is mentioned in the fourth chapter, in Oh Mercy, and Dylan’s remarks to the songs are introduced by a litany.

It is 1987 and everything is broken. His hand is mangled to the bone, the garden is overgrown, Dylan feels tired, wrung out, an empty burned-out wreck, on the bottom, everything was smashed. And so it goes on and on. Page after page the autobiographer gloomily grumbles over this point in his life, in his career that he has now reached and he describes with poetic urgency, in one after another remarkable metaphor (“even spontaneity had become a blind goat”) the depressing darkness that rules before he records the album Oh Mercy with Daniel Lanois.

“Everything Is Broken”, says Dylan, “was made up of quick choppy strokes. The semantic meaning is all in the sounds of the words.”

The latter is a mysterious addition, with the suspicion that the poet does not know exactly what the word semantic means. In words such as Broken lines, broken strings / Broken threads, broken springs, a very distinct sense of language is required in order to actually derive the meaning from the sound. Does “threads” really sound like what it means, threads, wires? Or “strings” like cords, strings? We have caught Dylan previously on a linguistic feeling, on a sense of language bordering on synesthesia, so who knows? To him it may sound that way.

At least as remarkable is the deleted verse that the master quotes here:

Broken strands of prairie grass Broken magnifying glass I visited the broken orphanage and rode upon the broken bridge I’m crossin’ the river goin’ to Hoboken Maybe over there, things ain’t broken

Remarkable, not only because it is so stylistically different from the rest, with those sudden, misty, Dylanesque images, but also because suddenly an optimistic spark flashes: maybe things are not broken on the other side of the river.

About thirty pages later, the song returns once more when Dylan tells about the recording session. Producer Daniel Lanois thinks the song is just a throw-away, Dylan suspects, but he himself is completely satisfied. And then another typical, confusion creating bonus comment follows:

“Critics usually didn’t like a song like this coming out of me because it didn’t seem to be autobiographical. Maybe not, but the stuff I write does come from an autobiographical place. [Lanois] was looking for songs that defined me as a person, but what I do in the studio doesn’t define me as a person.”

With these words Dylan succeeds (once again), to both open and close the door to autobiographical interpretation. My songs do come “from an autobiograpical place”, but do not “define me as a person”, do not characterize me.

So there are some marginal comments to be made. In the previous dozens of pages, Dylan has painted his emotional state of being in the year and a half before “Everything Is Broken” and only one characterization fits: kaputt. Lost in the rain of Juarez. A protagonist from a piece by Sam Shepard. Just like almost all the lyrics on the album express abandonment, dissolution and gloominess. In light of this, of his own testimonies about his mental attitude, it is not such a bold assumption to see “Everything Is Broken” as a characterization of the poet himself.

Dylan gets back on his feet, fortunately. The chapter Oh Mercy ends positively, with admiring words for Lanois and with the notion that they will work together again ten years later, in a rootin’ tootin’ way; nicely and pleasantly.

The pounding, swampy Creedence-like approach of Lanois and Dylan is appreciated by colleagues. Even Ben Sidran, the rock and jazz pianist who has produced a lot of challenging, idiosyncratic Dylan covers, remains reasonably within bounds this time (Dylan Different, 2009).

Bettye LaVette, the veteran who has done great Dylan covers in the past, seems to want to do a Tina Turner parody, but it is nevertheless a beautiful, soulful rendition (Thankful ‘N’ Thoughtful, 2012).

A lot of slide-guitars and greasy basses, of course: Tim O’Brien, R.L. Burnside, Kenny Wayne Shepherd and Larry Norman (“the Bob Dylan of Christian music”) are all perfectly comparable in terms of arrangement, tempo, instrumentation and sound – and all equally irresistible. Although … Larry Norman shuffles and jumbles up the words – which gives an original added value to a song called “Everything Is Broken”.

From the same Delta sound category the two most beautiful covers derive, scoring extra points because the artists both come from the immediate vicinity of the master. Billy Burnette played in Dylan’s band and has rock ‘n’ roll history in his genes. His sultry, heavy version is to be found on the fine album Memphis In Manhattan (2006).

Even more intensively, in the studio, Duke Robillard worked with Dylan. The Fabulous Thunderbird enriches hundreds of records with his playing as a session guitarist, helps Dylan and Lanois on Time Out Of Mind and also records piles of solo albums in between. The beautiful double album World Full Of Blues (2007) has a few highlights (the “Bounce For Billy” inspired by Charlie Parker, for example) and “Everything Is Broken” one of them. The guitars, of course, and the harmonica are the strongest points, but Robillard also suprisingly scores in terms of vocals – much less flat than elsewhere, in any case.

It is, as Sam Shepard said, a great song.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Well said. I like the focus on autobiography because I tend to believe that since 2001’s “Love & Theft” Dylan moves away from being personal in his songs and a powerful component of his writing is lost.

Obviously, co-writing songs with Robert Hunter will have a detrimental impact on this aspect of his writing ( and, to be honest, in general though ‘ Forgetful Heart ‘ is a lovely terse song ). The increasing and deliberate use of words from a myriad of sources also plays a part in removing the personal element. Still, we have many wonderful songs since 2001 and it could be argued that Dylan has developed another unique style of songwriting.

A good point but the way most of Dylan songs are written they stand the test of time even if you know nothing about his personal life because they have roots that go back into the history of traditional American songs.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/185/Everything-is-Broken

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.