by Jochen Markhorst

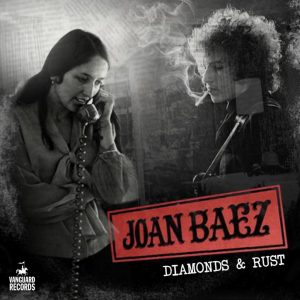

It is not really Joan Baez’ forte, writing songs, but at least once she rises above herself: “Diamonds & Rust” from 1975 really is a wonderful song. Definitely on a musical level, although the beauty may be due more to the sparkling arrangement than to the strength of the composition, but remarkably successful this one time are the lyrics and especially their tone.

It is not really Joan Baez’ forte, writing songs, but at least once she rises above herself: “Diamonds & Rust” from 1975 really is a wonderful song. Definitely on a musical level, although the beauty may be due more to the sparkling arrangement than to the strength of the composition, but remarkably successful this one time are the lyrics and especially their tone.

The lyrics of Baez are usually somewhat too larmoyant or one-dimensional and humourless (“To Bobby”, for example), lyrics that are, in Dylan’s words, ‘lousy poetry’. “Diamonds & Rust” is pleasantly mild-mocking, honestly poignant, melancholic and poetic, a song in which Baez looks back, without any bitterness, at her time with Dylan, at that time they lived together in that crummy hotel over Washington Square (Hotel Earle on MacDougal Street and Wavery Place, a four-minute walk from 161 West Fourth Street, incidentally) and she remains on the right side of sentimentality from start to finish.

Equally remarkable is the origin story. That story the singer tells in the song itself: out of nowhere Dylan reports by phone, from a booth in the Midwest (on February 4, 1974 Dylan is with The Band in Denver – that would be an educated guess) and in 2010, in the Huffington Post, she adds another detail. “He read me the entire lyrics of Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts, that he’d just finished.”

It inspires her to totally re-work the song she was just working on and to change it to “Diamond & Rust”; “It had nothing to do with what it ended up as.”

The inspiration comes, obviously, first and foremost from the unexpected conversation itself. But secondly perhaps also from the constellation of the acting persons in Dylan’s song: two attractive women and an inscrutable, mysterious stranger – it is only a small bridge to the triangle Sara (or Suze), Joan and Dylan. For the costuming of those persons, Dylan then apparently looks at his pack of tarot cards, from which he seems to draw more often in the 1970s. His mysterious hint from 1977, in the interview with Jonathan Cott, who tries to push him into all sorts of tarot symbolism, seems a vague confirmation: there’s a code in the lyrics, meaning the song lyrics of Blood On The Tracks. The continuation of that outpouring (“there’s no sense of time”) is comprehensible, but that code has not been cracked yet – if there is one, of course.

Dylan, in any case, inhibits the over-enthusiastic reach for The Pictorial Key to the Tarot (A.E. Waite, 1910). “I’m not really too acquainted with that, you know,” he says a half year later to the same Cott in a follow-up interview, when the journalist starts to blabber about all the tarot symbolism he has discovered in Dylan’s lyrics. And a few years later, in an interview with music journalist Neil Spencer, he repeats that evasion almost verbatim: “I didn’t get into the Tarot Cards all that deeply.”

Undoubtedly some echoes will have trickled down, that much is true. The names for example. The lily and the rose are the only flowers at the feet of The Magician, “the divine Apollo, smiling with confidence, with radiant eyes”, the tarot figure in whom Robert Shelton too thinks seeing traits from Bob Dylan (Melody Maker, July 29 1978) and to whom more references can be found (on Street Legal, in particular). And once in that tarot tunnel, references are to be found in each of the sixteen couplets. But in the end all those references are probably in the category that Dylan is referring to in his Nobel speech: “I’ve written all kinds of things into my songs. And I’m not going to worry about it – what it all means.”

Sobering words, in line with earlier relativizations with which Dylan dismisses the all too exuberant and pompous exegesis of his lyrics. Above all, it has to sound good, he says in the same speech – I have been influenced like everyone else, and it can mean anything.

This also applies to the symbols in this song. The lily and the rose, Lily and Rosemary, is one of those combinations that we can already find in the Bible, in the Song of Songs (2:1, “I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys”), a Bible book that is probably deeper under Dylan’s skin than those tarot cards.

In terms of content, the story is not easy to follow. The plot looks classic enough; on the surface it is a weekday cowboy novel with all the clichés involved. A mysterious stranger, a bank robbery, there is poker, the local landowner has an extramarital affair with the beautiful show girl, a public hanging, a saloon, a judge… images and archetypes we know from every western with or without John Wayne.

Fascinating the plot then gets because of Dylan’s tampering with time, much as he does in “Tangled Up In Blue” and “Simple Twist Of Fate”: a collage-like series of related impressions, the chronology is interrupted by short atmospheric images and introductions of the main characters.

The Jack of Hearts appears on the scene and turns the head of danseuse Lily, with whom he apparently already shares an amorous past. She is the mistress of the local big shot Big Jim, who is not exactly charmed by Lily’s crush. That leads to the climax, which takes place in Lily’s dressing room. Big Jim kicks open the door and pulls his revolver, but is stabbed from behind, presumably by his wife Rosemary, whose knees also get weak over the Jack of Hearts. It all comfortably distracts from the work of Jack’s gang members, who are prising open the wall of the bank, two doors down. Rosemary is hung the next day, Jack is gone with the booty and the fair Lily is left behind, contemplating.

A cinematic whole, all in all, and indeed two attempts have been made to translate the ballad into a film script. Neither of these scripts has produced a film, unfortunately.

That cinematic and the chosen impressionistic narrative style can certainly be attributed in part to Dylan’s recent experiences with Sam Peckinpah, the director of Pat Garett & Billy The Kid. That film offers Dylan his first serious acting experience (in the supporting role “Alias”) and puts him on the map as a film music composer, when “Knockin ‘On Heaven’s Door” becomes an acclaimed world hit, but the narrator Dylan has also been paying attention. Peckinpah is a cyclic narrator; he likes to finish his films at the beginning, and Peckinpah likes to tell choppily, with little time jumps and drawn-out intermezzos – just like Dylan is now shaping his ballad. The story begins and ends in a quiet cabaret, both with the sound of refurbishment work in the background, and unfolds with interruptions to introduce the main characters – except for the mysterious Jack of Hearts, who is mentioned in every verse, but about whom we come to know virtually nothing.

Cinematographic qualities also have the words the poet chooses in the descriptive, atmospheric intermezzi. If the camera leaves the action for a moment, having a quick glance at the scene and registering the entry of the judge, it lingers with Rosemary for a while: Rosemary started drinkin’ hard and seein’ her reflection in the knife. Harrowing, foreboding stage direction. It evokes dark premonitions and at the same time the sympathy of the viewer for the cheated Rosemary. Peckinpah could have handled it, such an ominous image, but alas, the director is busy these days, with Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia.

The music colleagues are reluctant to tackle the song. The story comes first, of course, and that slows down the desire to put energy and inspiration in a cover. Although there are dozens of amateur attempts to be found on YouTube, none of them surpasses amateurism.

Among the few professionals there are only two who may reside in Dylan’s shadow. Joan Baez first of all, who obviously can claim a kind of property right, or at least a right of use. Her version on the live album From Every Stage (1975) has the same big plus as the aforementioned “Diamonds & Rust”: beautifully arranged.

The same compliment can be given to Tom Russell, together with Joe Ely and Eliza Gilkyson on the album Indians Cowboys Horses And Dogs (2004). Both artists, Baez and Russell, struggle with the length of the song and search for musical solutions to hold attention, to add tension, not to lose momentum. That can often be observed at Dylan covers. A gifted performer like Dylan can repeat the musical accompaniment of any verse from “Tangled Up In Blue” or “Shelter From The Storm” or this Jack Of Hearts from beginning to end without any variation; his performance skills do the job. A Tom Russell, for example, is less talented, but has other skills – the ability to dress up the song so well and multicoloured that the music holds the listener (alternating singers, exquisite organ by Joel Guzman).

The artists who fail to do that, who like Dylan do not or hardly vary the musical accompaniment, usually disappoint: Mary Lee’s Corvette (on the otherwise very enjoyable tribute project Blood On The Tracks) and the sympathetic Rumpke Mountain Boys. Nice, but three minutes is quite enough.

To be fair: even the master himself does not dare to tackle the song live, apart from one unrecorded performance together with Joan Baez, during the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1976. And, of course, that intimate recital from a telephone booth in the Midwest.

Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts.

- Lily Rosemary & the Jack of Hearts (as I understand it): an alternative vision. By Ann Alenjandro

- Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack Of Hearts: revealing the source of this and other Dylan songs. Part 1. by Larry Fyffe

- Bob Dylan And Damon Runyon: Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack Of Hearts And Other Songs (Part II) by Larry Fyffe

- Source Of Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack Of Hearts (Part III)by Larry Fyffe

- Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack Of Hearts: revealing the source of this and other Dylan songs. By Larry Fyffe

- Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts: the meanings behind Dylan’s song By Tony Attwood (updated Nov 2017)

- Lily O’Valley, Mary Magdalena, and The Jehovah of Hearts: Bob Dylan mixes up the medicine By Larry Fyffe

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews