by Jochen Markhorst

A lot of great things can be said about “Blowin’ In The Wind” and in the Top 10 of the achievements of Dylan’s first classic is the fact that the song finally drove Graham Nash out of The Hollies. In his autobiography Wild Tales (2013), a rather embarrassing and humourless, but fascinating ego document in terms of rock music history, Nash recalls in Chapter 7 the run-up to the break. He gets to know David Crosby and makes a musical click, he falls in love with Joni Mitchell who overwhelms him with her songs, and at home in England he and his Hollies rise with “Jennifer Eccles” to the top of the hit parade. “It embarrassed me to hear that fucking song on the radio. Now we had to promote it as well. I felt like such a whore.”

A lot of great things can be said about “Blowin’ In The Wind” and in the Top 10 of the achievements of Dylan’s first classic is the fact that the song finally drove Graham Nash out of The Hollies. In his autobiography Wild Tales (2013), a rather embarrassing and humourless, but fascinating ego document in terms of rock music history, Nash recalls in Chapter 7 the run-up to the break. He gets to know David Crosby and makes a musical click, he falls in love with Joni Mitchell who overwhelms him with her songs, and at home in England he and his Hollies rise with “Jennifer Eccles” to the top of the hit parade. “It embarrassed me to hear that fucking song on the radio. Now we had to promote it as well. I felt like such a whore.”

In those days the boys propose to record a whole album with Dylan covers. Nash hesitates. Dylan is great, that is not the point, and David Crosby did great things with Dylan songs with his Byrds. “But an entire album of Dylan covers? Something about it sounded cheesy.” Eventually he is persuaded by producer Ron Richards, who does believe in it.

“But once we got into the studio, everything went wrong. The guys decided to make Dylan swing. The arrangements whitewashed the songs, giving them a slick, saccharine, Las Vegasy feel. They emasculated them, obliterated their power. We did a version of “Blowin’ in the Wind“ that sounded like a Nelson Riddle affair. It was a hatchet job, just awful.

“That was it, as far as I was concerned. No more Dylan. I put my foot down. I was convinced the Hollies had lost their focus. I thought we weren’t getting anywhere and perhaps we needed some time apart.”

The rest is history; Graham Nash fulfills his last obligations, The Hollies record the horrible Hollies Sing Dylan without him and by then he has left for America, to join David Crosby and Stephen Stills.

At the time of that Hollies cover the song is already the monument that it still is today and always will remain. “Blowin’ In The Wind” is what the Mona Lisa is to Da Vinci, Sonnet 18 (‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’) to Shakespeare, the Symphony No. 9 in D minor to Beethoven and The Thinker to Rodin – not necessarily the best work of a genius artist, but the best known, the work that immortalises the artist.

The exceptional class of the work is recognized immediately after the conception. The most alert response is from The Chad Mitchell Trio, who records the song first, four months before Dylan. The record company does not dare to release it on single, being rather hesitant about the use of the word death in the song. Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman takes advantage of that blunder.

His artist menagerie also includes the successful trio Peter, Paul And Mary and that neat trio knows what to do with the song. Their serious, stately version is a huge hit and that brings in some money. To Dylan’s astonishment, as Peter Yarrow remembers: “I told Bob he might make $5,000 from the publishing rights. He was almost speechless; it seemed like a fortune.”

The song, the open and repeated tributes and recommendations by Peter, Paul And Mary and, later on, the promotion to protégé of Joan Baez, launch the career of the young bard. A few months later, at the Newport Folk Festival in July ’63, Dylan is already the undisputed crown prince of the folk community.

“Blowin’ In The Wind” is raging around the world by then and has already left a crater in the United States. The black community also picks up the song, probably in part due to the gospel undertones of the melody. It contributes to the unifying, universal power of the song – apart from the non-specific, poetic vagueness of the lyrics, the chosen music also has a race- and culture-transcending quality.

Coincidence, of course. Dylan has not planned this success and can not foresee that the song will grow into the hymn of the civil rights movement, of the Sixties as such, even. But: a calculating cold-blooded strategist could not have figured it out craftier. The melody comes from an old slave song from the nineteenth century, “No More Auction Block”, which Dylan admits easliy, like in the interview with Marc Rowland, in 1978.

In a radio broadcast of National Public Radio, October 2000, comrades from day one, Happy Traum and Bob Cohen (from The New World Singers) recall more details:

One night at Gerde’s Folk City, Dylan heard The New World Singers perform a Civil War era freedom song, one that Bob Cohen still remembers.

“It was very dramatic and a very beautiful song, very expressive. And Dylan heard that and heard other songs we were singing. And some days later, he asked us, he said, `Hey, come downstairs.’ We used to go down to Gerde’s basement, which was—is it all right to say?—full of rats, I don’t know, and other things. And he had his guitar, and it was kind of a thing where when he added a new song, he’d call us downstairs and we’d listen to it. And he had started—and he wrote, (singing) `How many roads must a man walk down before you can call him a man?’ And the germ of that melody of “No More Auction Blocks” certainly was in that.”

Success has many fathers, but Bob Cohen’s story is credible. Not only because Dylan himself, unasked, calls that song as a source, but also because he tells in his autobiography Chronicles that he was ‘pretty close’ with The New World Singers at that time.

The unifying quality is evident from the eagerness with which black artists, and not the leasts, put the song on the repertoire. It motivates one of the greatest names, Sam Cooke, to write that other hymn of the civil rights movement, “A Chance Is Gonna Come”, the song that shortly after Cooke’s premature death in December ’64 will reach mythical significance. In his thorough biography Dream Boogie: The Triumph or Sam Cooke (2005), Peter Guralnick reconstructs the influence of “Blowin’ In The Wind” on Sam Cooke:

“When he first heard that song he was so carried away with the message, and the fact that a white boy had written it, that . . . he was almost ashamed not to have written something like that himself.”

An earlier, equally serious biographer, Daniel Wolff (You Send Me: The Life and Times or Sam Cooke, 1995) agrees:

“The soul singer and former gospel star was further inspired when he heard Peter, Paul and Mary singing Dylan’s song on the radio. The folk trio piqued Cooke’s commercial ambitions. Their recording proved that a tune could address civil rights and go to No. 2 on the pop charts. For Cooke, the result of these racial and artistic challenges was “A Change Is Gonna Come“.”

In Chronicles Dylan admires the power of expression of that song, he regularly honours Sam Cooke in his Theme Time Radio Hour, even produces a respectful reverence (“I Feel A Chance Comin’ On”) on Together Through Life (2009) and sings a beautiful rendition (Apollo Theatre, 2004), but he never discusses his own contribution to Cooke’s masterpiece. Modesty, probably.

The amazement that a white boy can write something like this, Sam Cooke shares with Stevie Wonder. Little Stevie’s version reaches the top 10 of Billboard in ’66, and even the first place on the R&B list. That an anti-war song can score that high is already meritorious, but according to Stevie the real achievement is that a white folk protest song can penetrate deep into the black neighbourhoods of the big city.

However, some objections could be made to both qualifications. For one, the source of the melody from that ‘white folk protest song’ is a black slave song, and second, the lyrics are far too general to stick the label anti-war song on it. The archaic cannonballs that the singer wants to banish forever already have stopped flying long ago (and are more likely metaphorical, anyhow) and the many unnecessary dead from the last lines may just as well refer to victims of unspecified violence, do not explicitly refer to war in any case.

The other fourteen lines protest, in various areas such as cowardice, stubbornness and self-centeredness, at most against human, moral failure in general.

The chosen images are so universal, poetically vague and age-old (from the bible book Ezekiel, for example), that the song allows a multitude of interpretations. In extremis one might defend, ironically enough, that Dylan actually wanted to write a diss, wants to dismiss the left-wing muddleheads with their impractical ‘solutions’ for world peace.

Those so-called solutions of you, the poet argues, are as elusive and airy as the wind. This possible interpretation is not that crazy. Dylan definitely has an intrinsic aversion to warmongering, racial segregation and discrimination, but just as strong a distaste for the humourless, self-glorifying, rigid do-gooders and starry-eyed idealists who claim the front seats of the civil rights movement. A year later he will opt out of all those peace marches, the protest meetings, the charity performances.

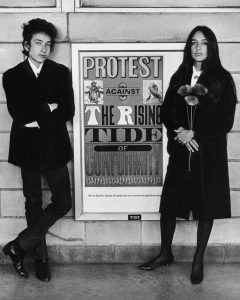

The naive, quasi-profound but terribly superficial croaking of all those self-important posers – Dylan really does not want to belong. They have to content themselves with Joan Baez. The famous photograph of Daniel Kramer, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez with Protest Sign, Newark Airport 1964 (it is actually a poster promoting Booth’s House of Lords Gin), makes that visible: where Joan Baez flawlessly controls the pose and air of the Principled Warrior for the Righteous Cause, in Dylan’s eyes boredom, ridicule and cynicism jostle for predominance. It ain’t me, babe, one can almost see him think.

But the writer’s intention ultimately is unimportant. “Blowin’ In The Wind” is an art transcending masterpiece that elevates and connects people, which is quoted by judges, popes and presidents and will still be sung by our great-grandchildren.

Except for those of The Hollies, obviously. They are not allowed.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Blowing in the Wind: the meaning of the music and the lyrics

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/78/Blowin-In-The-Wind

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.