by Jochen Markhorst

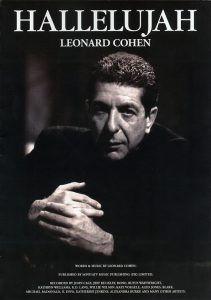

It is an anecdote that Leonard Cohen likes to tell, apparently, for it can be read in many interviews. It refers to his late magnum opus, the wonderful song “Hallelujah”, the song that surprisingly but gradually climbed up from little-noticed album track (on Various Positions, 1984) to a classic, to one of his most loved and most covered (more than three hundred versions) songs.

It is an anecdote that Leonard Cohen likes to tell, apparently, for it can be read in many interviews. It refers to his late magnum opus, the wonderful song “Hallelujah”, the song that surprisingly but gradually climbed up from little-noticed album track (on Various Positions, 1984) to a classic, to one of his most loved and most covered (more than three hundred versions) songs.

That triumphal march begins in 1991, when John Cale wants to do the song for the tribute album I’m Your Fan. Cale notices at a concert that Cohen sings different words than on the record and he asks the Canadian for the correct lyrics. Cohen, who by his own account never could finish the song and would write over eighty couplets, faxes fifteen couplets.

Cale picks out five of them. “It was a long roll of fax paper. And then I chose whichever ones were really me. Some of them were religious, and coming out of my mouth would have been a little difficult to believe. I chose the cheeky ones.” This variant is picked up by Jeff Buckley, who records an unforgettable version for his first and only album, Grace from 1994. Ten years after his death in 1997, it is released as a single, after being included in Rolling Stone’s list of The Greatest Songs Of All Time (in 2004, at 259).

But Dylan deserves the credit for recognizing the greatness of the song much earlier. He sings “Hallelujah” as early as July 8, 1988, in Cohen’s hometown of Montreal and again a few weeks later, in Los Angeles. The men have known and appreciated each other for a long time, but this really flatters Cohen, which is why he brings it up regularly, in various interviews.

“That was a song that took me a long time to write. Dylan and I were having coffee the day after his concert in Paris a few years ago and he was doing that song in concert. And he asked me how long it took to write it. And I told him a couple of years. I lied actually. It was more than a couple of years.

Then I praised a song of his, “I and I”, and asked him how long it had taken and he said, ‘Fifteen minutes.’ [Laughter]”

It is true, there are many testimonies from bystanders who tell that Dylan so phenomenally fast dashes off song lyrics. George Harrison says that Dylan produces the world hit “Handle With Care” in a few minutes, close comrades-in-arms like Al Kooper, Kevin Odegard and Duke Robillard have throughout the decades all completely similar memories of a Dylan who, in between studio turbulence, card-playing musicians and tea ladies, aside at a coffee table quickly adds a verse or writes a complete song lyric, but still: Leonard Cohen inquires after the wrong song.

He should have asked about “Tangled Up In Blue”. That is the song that according to Dylan took him two years to write and ten years to live, and thereby he refers to his years of marriage with Sara Lownds.

“Tangled Up In Blue” opens Blood On The Tracks (1975), the record that, rightly or wrongly, is considered the most beautiful divorce record in pop history, and one of Dylan’s Great Masterpieces. Most of the lyrics on this album are poignant, moving, poetic and sometimes painfully clear, but this highly acclaimed Tangled is far from unambiguous.

This lack of clarity is first of all caused by the confusing use of personal pronouns (the nameless I, She and He) and secondly by the inconsistency in time, which leads to an ardent puzzling, cutting and pasting of interpreters in order to find a linear narrative. Verse sequence 3-4-5-6-1-2-7 then provides, with some inching, squeezing and pinching, a more or less coherent rise and fall of a love story. Other exegetes quote Dylan’s own words:

“I wanted to defy time, so that the story took place in the present and past at the same time. When you look at a painting, you can see any part of it or see all of it together. I wanted that song to be like a painting.”

That does shed some light. “Tangled Up In Blue” poetically tells us that the storms of life leave their marks and that we are becoming a different person along the way. Dylan rightly chooses the collage technique and gives sufficient hints to justify a biographical interpretation. Sara was not only a model but also Playboy bunny (She was workin ‘in a topless place), and indeed still married when they first met. In his early years Dylan sometimes plays in a joint on Montague Street and he lives with a couple in the neighbourhood, he is originally from Minnesota (the Great North Woods) and recalls his Girl From The North Country. For the title explanation, Dylan has also lifted a more prosaic tip of the veil: to the journalist Ron Rosenbaum he reveals that he wrote the song after having immersed himself in the music of Joni Mitchell’s Blue for a weekend.

One could go on like this for a while, but it is not all too relevant for the lyrical power of this song. Dylan the Poet expresses here how this protagonist’s life too is defined by the oldest cliché, how a life can be summarised in the three words Searching For Love – love is all there is, as he sang a few years earlier. You find love, you lose it, and you go on. Keep on keepin’ on, headin’ for another joint.

To make it even more difficult for the Dylan interpreters: there is no song in his catalogue with which Dylan has scraped and tinkered so much. In September 1974 he records the first two versions, which still are largely told in the third person. There are some small textual differences between the two versions, the first version is ultimately chosen for the LP. Dylan then stays with his family in the North over Christmas. He shares the recordings from New York, a few hours before the records will be pressed, and brother David expresses concerns. Dylan agrees and re-records five songs with local musicians. Tangled receives the most radical make-over on all fronts (different keys, different instrumentation, tempo), and, by extension, also lyrically. That version is released on Blood On The Tracks.

In the following years, Dylan continues to rewrite and ultimately declares the 80s version (to be heard on Real Live from 1984) the final. Hardly any line is maintained in this re-issue. That is not the only clue to reveal Dylan’s own fascination; to this day the song belongs to his most performed. On the list of indefatigable Dylan watcher Olof Björner from Sweden it occupies the fourth place for years now, with more than a thousand performances, after “All Along The Watchtower”, “Like A Rolling Stone” and “Highway 61 Revisited”. Björner’s painstaking monk’s work registers all official concert performances since 1958. Statistically, Tangled should actually even rank a bit higher; the first fifteen songs on that list are, except for Tangled, all written between 1963 and 1968, and thus have a lead of up to twelve years. A “Blowin’ In The Wind”, for example, is twelve years older, but since long has been taken over – Dylan has sung “Tangled Up In Blue” over a hundred times more often than that monument.

And it does not stop there, Dylan’s own fascination. In his wonderful book Why Dylan Matters, Harvard professor Richard F. Thomas points out the return of the image of the waitress in 1997, in the overwhelming song “Highlands” on Time Out Of Mind. In the alienating intermezzo halfway through the song, in those seven couplets that create a kind of one-act play for two in an empty restaurant in Boston, we recognize the male protagonist from “Tangled Up In Blue”. He is in the ‘wrong time’, he picked the wrong time to come, says the waitress, who has thrown him back in time through her looks and behavior, back to 1974.

Just like her predecessor, she carefully studies the restaurant guest (She studied the lines on my face vs. She studied me closely), we are back in an empty catering facility and when he draws her portrait at her insistence, he must strangely enough draw it from memory, although she is still standing in front of him. There is absolutely no resemblance, she says a moment later, throwing the drawing back at him. On the contrary, the satisfied artist speaks to her, there most certainly is – after all, he has made a lifelike portrait of that waitress in that topless place. The final verse, when the waitress asks which female authors he has read, illustrates once again that the narrator is in a different time zone. “Erica Jong,” he answers triumphantly. Jong’s controversial Fear Of Flying is from 1973.

Fellow musicians share Dylan’s enthusiasm for the song. There are more than a hundred cover versions in circulation, but here too, more than ever, is the harsh truth: it is not easy to step out of the master’s shadow. Most artists fail to hold the tension, the urgency – if the artist, like Dylan, colours the seven couplets in the same way seven times, then it does require some mastery to avoid tediousness. Only the master craftsman is able to restrict himself, as Goethe taught, and here too only a few remain standing. Jerry Garcia, Dickey Betts and especially a remarkable Ben Sidran (Dylan Different, 2009) are doing very well.

The best cover though, by far, is from the Indigo Girls, on their live album 1200 Curfew (1995). Particularly respectful and lovingly executed, with a beautiful progression in the arrangement, tastefully dosed singing together and a very successful turnaround in rhythm and orchestration in the sixth verse (I lived with them on Montague Street) – they most certainly do not restrict themselves. And right they are.

Leonard Cohen never dared to. In 1985 “Tangled Up In Blue” is number two in his personal top five, as can be learned from the book In His Own Words by the devout Cohen fan Jim Devlin (number one is Ray Charles’ “Take These Chains From My Heart”) and the song is untouchable. Cohen often and heartily professes his awe for Dylan’s masterpiece, but not on stage. In interviews, yes. And majestic, poetic actually, is his commentary on Dylan’s Nobel Prize: It’s like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.

Elsewhere:

Dylan’s “Tangled up in blue”. The meaning of the lyrics and music of the original version

Tangled up in Blue: Bob Dylan’s utterly transformed “Real Live” version

If you’re going to cover another artist’s song, especially if that artist is Bob Dylan, make sure you bring something new and worth hearing to the table. Indigo Girls bring spirit and verve but not sure that change in rhythm you mention is up to much. All in all, it’s okay and pleasant enough. Ben Sidran? Meh. Jazz-lite with a little faux-rap feel. At points he even screws up the natural scansion. Basically, proof, if it were needed, that nobody sings Dylan like Dylan.

Jeremy I agree no one sings Dylan like Dylan, but for me, as a person who has performed the song on stage without ever feeling I brought anything new to it (but desperately wishing I could) I think both versions mentioned have added a lot to my grasp of the potentials in the lyrics.

The change of rhythm came to me as a total shock first time I heard it and forced me to listen to the familiar words from that point on in a different way, and for me, musically it works.

I think that for many of us, hearing a version by someone other than Dylan after becoming so used to the Dylan version, can jar, not because it is not well-founded musically but because it is different.

My favorite version is on the “Real Live” album.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/620/Tangled-Up-in-Blue

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.