Tell Me That It Isn’t True

by Jochen Markhorst

“I Heard It Through The Grapevine” is the first song of the legendary Motown duo Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield and an indestructible classic right away. No chance hit either; they write dozens of songs, and among them there are quite a few monster hits and masterpieces. “Papa Was A Rolling Stone”, “War (What Is It Good For)”, “Just My Imagination”, “Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home)”, just to name a few.

“I Heard It Through The Grapevine” is the first song of the legendary Motown duo Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield and an indestructible classic right away. No chance hit either; they write dozens of songs, and among them there are quite a few monster hits and masterpieces. “Papa Was A Rolling Stone”, “War (What Is It Good For)”, “Just My Imagination”, “Wherever I Lay My Hat (That’s My Home)”, just to name a few.

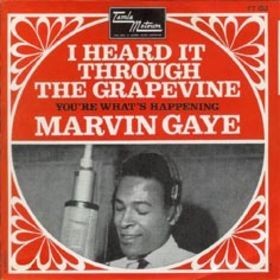

Initially, Grapevine is written for and in August ’66 recorded by The Miracles, but only the third version, with Gladys Knight & The Pips (September ’67), will be released on single and it reaches number two on the Billboard Chart. In the meantime, in the spring of 1967, Marvin Gaye records his now classic version for his breakthrough album In The Groove. Diskjockeys continue to run Gaye’s album track and finally, in October ’68, Motown decides to release that version as a single too. The song immediately rises to number one and stays there for nine weeks, until the end of January ’69. It is Motown’s biggest hit so far, scores high in the various All Time Best Songs lists and is inevitable in documentaries and films about the late 60s (although often the driven, drawn-out cover by Creedence Clearwater Revival is chosen) .

When Dylan, in his hotel room at the Ramada Inn in February ’69, quickly knocks together a couple of songs for the next recording day in Nashville, “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” still echoes through the streets, cafes and hotel lobbies. And with that, established Dylanologists such as Clinton Heylin and Tony Attwood argue, the inspiration for the undervalued “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” has been explained.

Definitely thematically, but also in terms of content, the similarities seem undeniable. Just compare the opening lines of the world hit,

I bet you’re wonderin’ how I knew

‘Bout your plans to make me blue

to Dylan’s words:

I have heard rumors all over town

They say that you’re planning to put me down

… and the link is clear. Still, it is unlikely that Grapevine is the real source of inspiration – at best it is the trigger to the song that is much deeper in Dylan’s genes, to the artist who is much closer to him, to Hank Williams’ “You Win Again”.

Dylan’s admiration for Hank Williams is devout. In the autobiography Chronicles, he expresses his admiration for Luke the Drifter without restraint:

“In time, I became aware that in Hank’s recorded songs were the archetype rules of poetic songwriting. The architectural forms are like marble pillars and they had to be there. Even his words — all of his syllables are divided up so they make perfect mathematical sense. You can learn a lot about the structure of songwriting by listening to his records, and I listened to them a lot and had them internalized.”

Agreed, perhaps an all too sophisticated word choice, and that forms like marble pillars is not entirely coherent, but his meaning is clear: to Dylan, Hank Williams belongs to the Really, Really Great Ones, in terms of status comparable with Woody Guthrie and Elvis.

In the hundred episodes of his radio program Theme Time Radio Hour Hank is frequently played (eight times), never without obeisances: “One of the greatest songwriters who ever lived,” ttrh 17, and: “Made some of the most beautiful songs about living in a world of pain,” ttrh 7. And he loves to play them, too. From the Basement Tapes Complete we know Dylan’s version of “Be Careful Of Stones That You Throw”, the song Dylan learned from Hank Williams’ alter ego Luke the Drifter, and of course “You Win Again”.

“You Win Again” is a bitter country blues that Williams records one day after his divorce from Audrey Williams and expresses the betrayal that Hank feels. “The songs cut that day after Hank’s divorce seem like pages torn from his diary,” biographer Colin Escott says.

The opening words of this particular song resonate much more clearly than those of Grapevine in “Tell Me That It Is Not True”:

The news is out, all over town

That you’ve been seen, a-runnin’ ’round

His adulation of Hank Williams in Chronicles illustrates the impact of these words: “When he sang ‘the news is out all over town,’ I knew what news that was, even though I didn’t know.” And one line hereafter we see that Dylan is now making the same associative leap as in 1969: “I’d learn later that Hank had died in the backseat of a car on New Year’s Day, kept my fingers crossed, hoped it wasn’t true.”

In interviews from that time Dylan emphasizes that these songs, the songs on Nashville Skyline, come from within:

“The songs reflect more of the inner me than the songs of the past. They’re more to my base than, say John Wesley Harding. There I felt everyone expected me to be a poet so that’s what I tried to be. But the smallest line in this new album means more to me than some of the songs on any of the previous albums I’ve made.”

(interview in March ’69 with Hubert Saal for Newsweek)

And in the Rolling Stone interview with Jan Wenner that takes place in May, Dylan tells enough humbug (“When I stopped smoking my voice changed… So drastically, I couldn’t believe it myself”), but credible is the statement that he arrives in Nashville with only a few songs in his pocket, and dashes off the other songs on the spot. Clinton Heylin, who is completely on the wrong track by supposing that “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” is a parody of “I Heard It Through The Grapevine”, analyzes accurately again that the song belongs to the songs which, like a Basement Tape, in a short creative flash bubble up out of nowhere. Apart from Dylan’s own words and the studio logs, the simplicity of the text also appears to support that assumption.

Indeed, there is no trace of Blonde On Blonde’s poetry, not an inch of John Wesley Harding’s depths. Clichés from the country idiom, rhymes like the ones that have been bouncing off these studio walls in Nashville thousands of times, although the poet seemingly deliberately, sometimes, turns to irony: he’s tall, dark and handsome (it’s not too realistic that a betrayed lover describes his rival as an irresistible Cary Grant).

Nevertheless, it is a beautiful, if not: professional song and it is not entirely understandable that its status has remained so far behind “I Threw It All Away” and “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here With You”. The master himself also ignores the song for a long time; it takes thirty-one years, until March 2000, before he plays it on stage for the first time. But then Dylan actually seems to recognize the beauty of this old shelf warmer. “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” will remain on the setlist until 2005 and is finally adequately rehabilitated after some eighty performances.

Satisfactory, but too late for an overall revaluation. The rest of the music world neglects this unsung Dylan pearl, so this work belongs to the rather select club Dylan songs of which hardly any covers have appeared. From Beck circulates a mediocre living room recording and he is the only artist from the Premier League that plays the song at all.

The Rosewood Thieves, folk rockers from New York, the indie rock band Kind Of Like Spitting (on Professional Results, 2014) and the remarkable Jolie Holland are worth mentioning from the lower echelons. Jolie Holland, who is rightly classified as New Weird America, is blessed with a smooth, drawling vocal style and repeats her idiosyncratic homage to Dylan on her album Wildflower Blues (2017); there she conjures up Dylan’s forgotten “Minstrel Boy”.

Just like Jolie Holland, Richard Janssen from Utrecht has a faible for Dylan’s orphaned disposables. In 1998, for a so-called 2 Meter Session, he records a beautiful “If Dogs Run Free”. Ten years earlier, with his Fatal Flowers, one of the best Dutch bands of the 80s, he records the most beautiful cover of “Tell Me That It Isn’t True”, also for a 2 Meter Session on vara Radio. The Fatal Flowers are in the history books thanks to the very nice hit “Younger Days”, but the other songs also stand the test of time well. The recording of “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” is successful enough as to be selected in 2002 for the nostalgic collection album Younger Days – The Definitive Fatal Flowers.

He truly was tall, dark and handsome, our Richard Janssen.

You might also enjoy: Tell me that it isn’t true: the meaning behind the words and music.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

… and years later we get:

‘They’re braggin’ about your sugar

Brag about it all over town…’ (Spirit on the Water)

Some things don’t change!

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/625/Tell-Me-That-It-Isn't-True

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.