by Jochen Markhorst

In a New York hotel room, as some guy named Joe from Minneapolis fables on songfacts.com, a Grateful Dead party gets out of hand. Dylan is there too and he is especially amused at the complaints of another famous hotel guest: the actor Anthony Quinn.

In a New York hotel room, as some guy named Joe from Minneapolis fables on songfacts.com, a Grateful Dead party gets out of hand. Dylan is there too and he is especially amused at the complaints of another famous hotel guest: the actor Anthony Quinn.

There you have it, the source of inspiration for the song. The Grateful Dead is still a relatively unknown band in the summer of ’67 (their first, not particularly notable LP is just three months out), the first time that Grateful Dead is in New York is June 17, ’67 (coincidentally the same day that the murders are committed for which Rubin “Hurricane” Carter will be convicted), and no source mentions that Dylan left the Basement and West Saugerties that June to rebuild a hotel room in New York with Jerry Garcia, but Joe from Minneapolis prefers to ignore these insignificant details.

Jerry from Poughkeepsie knows better: this is “of course” about fun spoiler Sheriff Larry Quinlan, who arrested the LSD guru Dr. Timothy Leary in 1966.

And these are just two of the many quite desperate interpretation attempts that are circulating. “The coming of the Messiah” is another popular one, an even sadder one actually.

The nonsensical, exuberant text of “Quinn The Eskimo” is a magnet for Dylan exegetes with crypto-analytical ambitions, that much a tour along the comments on this song makes clear.

That Dylan himself has repeatedly stated that this song is really not about anything, is preferably ignored and sometimes denied. Obviously, a poet’s unconsciously expressed outbursts can also tell a story or reveal a message, but in this case hidden meanings really do seem far-fetched.

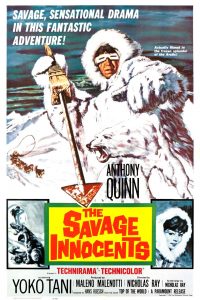

“I don’t know what it was about,” Dylan confesses in the Biograph booklet (1985), “I guess it was some kind of a nursery rhyme.” And in an old interview with John Cohen in 1968, shortly after the Big Pink days, he confirms that there will probably be a link with that Eskimo film with Anthony Quinn (meaning The Savage Innocents from 1960, in which, absurdly, the Mexican Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca indeed does play an Inuit), but: “I didn’t see the movie.” It could have triggered it, the journalist insists. Of course, says Dylan, giving in, sometimes you might overhear something. “I know the phrase came about, I believe someone was just talking about Quinn, The Eskimo. ”

Robbie Robertson has fewer doubts. And as a witness of the first hour, he is of course not only entitled to speak, but his words (in Testimony, his autobiography from 2016) also do have a bit more value than the conspiracy theories of hogwashing nitwits on the Plughole of the Occident, the internet forums. Robertson reports:

“Howard Alk and his wife, Jonesy, Albert and Sally Grossman, and Al Aronowitz all came out to Big Pink to see what was going on. They could tell we were having too much fun. We had just recorded “Quinn the Eskimo” with Anthony Quinn in mind—he’d portrayed a memorable character, Inuk the Eskimo, in the 1960 film The Savage Innocents.”

The words “having too much fun”, refer to the preceding paragraph, in which he tells they had just smoked “a J”. Which, in turn, also sheds light on the depth of the lyrics, obviously. And, admittedly, alone the insane fact that Antonio from Chihuahua is cast for the role of an Inuit is enough to inspire a farcical novelty song.

In Chronicles the song title pops up too, again in connection with a film. During the recording sessions for Oh Mercy (1989), Dylan walks in New Orleans past a movie theater where The Mighty Quinn is shown, a Jamaican thriller starring Denzel Washington as the mighty Xavier Quinn, a crime-solving detective. “Funny,” writes Dylan, “that’s just the way I imagined him when I wrote the song” – with which he, very Dylanesque, suddenly implies knowing what the song is about after all.

Some literary handiwork has been attended to it, that much is true. Each chorus has an antithesis, one varying verse line that then always contrasts with the preceding verse (despair – joy, on a limb – going to run, no sleep – doze), there is a cast-iron rhyme scheme and the wording does suggest a deeper meaning. The half reference to Noah (shipbuilding, pigeons) fits Dylan’s flood fascination, which he airs at more Basement sessions (“Down In The Flood”, “Tupelo”, “Big River”), but further attempts to finding a message or a story are ridiculous – it just isn’t there.

Manfred Mann deserves most of the praise. During a listening session where tracks from the unpublished Basement Tapes are revealed to a select club of musicians, he is the only one who recognizes the potential in those messy and rattling two minutes of Quinn. Dylan is not at his best at this recording. It does sound musty and perfunctorily. The master seems even a bit bored and whiny, as a matter of fact (singer Mike d’Abo: “It was sung in a rambling monotone”). Mann squeezes the song in a tight, poppy arrangement and blows up the verse into stadium-worthy sing-along proportions.

Mike d’Abo, who actually wanted to choose “This Wheel’s On Fire”, has difficulty understanding what Dylan is singing, and is forced to flee to a kind of onomatopoeically sound echoing of what he thinks he understands (It was like learning a song phonetically in a foreign language). “I have never had the first idea what the song is about,” he adds, “except that it seems to be Hey, gang, gather round, something exciting is going to happen ’cause the big man’s coming. As to who the big man is and why he is an Eskimo, I don’t know.” (in 1000 UK #1 Hits by Jon Kutner and Spencer Leigh, 2005).

It was, says drummer Mike Hugg in Mannerisms (Greg Russo, 2011), as with most major hits by Manfred Mann, quite a chore: “We had huge problems with Mighty Quinn. We just couldn’t finish it. We kept going back to the studio to try other things. It took us ages to get it right. ”

But a few hours after finishing it, the initial relief evaporates again, as Manfred reveals. After the exhausting recording sessions, he goes home, listens once more in all peace and quiet, and doesn’t like it after all. He rejects the song, and the others just accept his rejection. The song has already been forgotten, when D’Abo calls Manfred a month and a half later. He played an acetate to Lou Reizner from United Artists and both, D’Abo and Reizner, are convinced that it will be a success. He persuades everyone to come and listen again at his home.

“When it was played at Michael’s house, it sounded very good, and I felt pretty foolish. I just couldn’t believe that I could have made such a mistake. Then I asked Michael whether his turntable could have been running fast, and we checked and found that his record turntable was running a semi-tone fast. We then went into the studio and did the work that Mike Hugg referred to. We speeded up the record a semi-tone for release.”

A new, catchy intro is also added: Klaus Voormann, the German bass player, fifes the characteristic tune on his flute and bingo, now (January 1968) we have a world hit – and indeed, for years several sports clubs let the chart breaker blare through the stadiums.

The South African band leader cannot do much wrong with the master anyway, after the previous hits with his songs (“Just Like A Woman”, “With God On Our Side” and “If You Gotta Go, Go Now”). Already in December ’65 Dylan publicly declares that this British band does the most justice to his songs. “Each one of them has been right in context with what the song was all about.” He will therefore have peace with the fact that the song moves to Manfred Mann’s catalog. The appearance on the setlist of Wight, 1969, is probably a gift to the English public. That performance also appears on Self Portrait and on Greatest Hits Vol. II, but then Dylan lets the song rest for 33 years and only plays it again in 2002 (four times) and 2003 (one time, again in England).

Others are more enthusiastic. Grateful Dead plays it often in the encore (59 times), for Manfred Mann’s Earth Band it is even the most played song and the list of covers is endless.

The majority of the covers gratefully adopt the revelry of Mann’s approach. And therefore have little added value, although the metal angle by the Swiss rockers of Gotthard (2003) is funny. Kris Kristofferson’s sober, folky version on Chimes Of Freedom (2012) is quite a relief. Paul Weller tries, together with Sam Moore and Amy Winehouse, to dress up Quinn in a soul jacket, but stumbles over the non-stop party content of the sing-along chorus, too.

No, Manfred Mann’s own revision, with the Earth Band, still is the most distinctive. The best known is, live with overdubs, on the hit LP Watch (1978). Reviled among die-hard Dylan fans, but Manfred plays his hit at every performance since 1971 to this day, and continues to vary. The long, spun out versions sometimes degenerate into improvised jazz rock, then again into screaming hard rock or worn, pompous symphonic rock, but the band invariably brings the song “home” again; out of the chaos the familiar chorus peeps up again, and a relieved audience may – sometimes a capella – sing along.

Whatever else we may think of it: Manfred Mann transforms the faltering, slightly bizarre, misty, unsightly, dadaesque lightweight nonsense rhyme from the Basement Tapes into the indestructible pop historical monument it is today.

Manfred Mann’s Earth Band, 1978:

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Anthony Quinn stars in ‘La Strata’ which rather like ‘Children Of Paradise’, depicts life as a travelling circus of sorrowful clowns, both of which seem to have quite a bit of influence on Bob Dylan, ie ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/508/Quinn-the-Eskimo-The-Mighty-Quinn

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.