by Jochen Markhorst

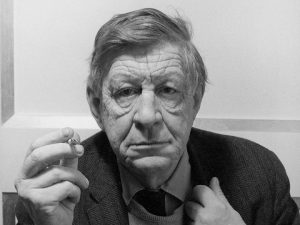

Wystan Hugh Auden (1907-1973) does leave a mark on John Wesley Harding indeed. For “The Wicked Messenger” Dylan borrows the striking rhyme scheme and structure of Auden’s “In Schrafft’s”, and for “As I Went Out One Morning” the bard even copies rhyme scheme, structure and words from “As I Walked Out One Evening”.

Wystan Hugh Auden (1907-1973) does leave a mark on John Wesley Harding indeed. For “The Wicked Messenger” Dylan borrows the striking rhyme scheme and structure of Auden’s “In Schrafft’s”, and for “As I Went Out One Morning” the bard even copies rhyme scheme, structure and words from “As I Walked Out One Evening”.

It gives some substance to the scornful words that an anonymous critic devotes to Dylan in the article “Public Writer No.1?” in the New York Times of December 12, 1965:

“Granted, he has an interesting imagination, but his ideas and his techniques are dated and banal–we’ve been through all this before in the thirties. Like most pop culture heroes, Dylan will soon be forgotten–he’ll quickly become last year’s vogue writer.”

In the same article, W.H. Auden is asked about his opinion on Dylan, whether he sees in Dylan the new Public Writer No.1. But the old poet, regrettably, has to pass:

“I am afraid I don’t know his work at all. But that doesn’t mean much–one has so frightfully much to read anyway.”

It is not unfriendly; in 1965 the brilliant Anglo-American poet is by no means the only intellectual who really is totally unaware of Dylan or pop culture at all – and he himself stands in the eyes of authoritative literature critics, juries and art tsars miles above the young bard from Duluth. Not that he feels exalted. In her enchanting autobiography, Marianne Faithfull describes cheerfully and with sympathy a meeting with the villainous, provocative Auden:

I remember going to a dinner with Tom Driberg and W. H. Auden. In the middle of the evening Auden turned to me and in a gesture I assume was intended to shock me said, “Tell me, when you travel with drugs, Marianne, do you pack them up your arse?”

“Oh, no, Wystan,” I said. “I stash them in my pussy.”

At that time (1968) Faithfull idolizes Dylan and she drives her life partner Mick Jagger to the limit by endlessly playing her tape with the fourteen Basement songs. So Dylan may have been discussed during that dinner with Auden too, but unfortunately her book does not tell (Faithfull. An Autobiography, 1994, in which she also exuberantly shares her experiences with and observations of Dylan).

Auden’s jabbing reminds of how Dylan and his partner in crime Neuwirth try to provoke table mates and other bystanders in the mid-sixties. But both poets are especially comparable at a level above. In terms of status, Auden is still a few steps higher in the pantheon in 1965, but then Dylan catches up with the Englishman. From the twenty-first century the roles have been definitively reversed and now Auden is invariably compared with Dylan. Not only on a literary level, but in particular the man’s cultural impact matches:

“In 1939, Auden held a position that can only just be suggested by that of Bob Dylan in 1967: indisputably the voice of his generation, he also wrote in a style so cryptic and allusive that the generation puzzled over what exactly it was that they were supposed to be saying. Something about war and doubt and sex and mining machinery . . .”

(“The Double Man”, The New Yorker, 15 September 2002)

Like in New York Review Of Books (“an intellectual British 1930s version of Dylan in the early 1960s”, October 2015) and in the LA Weekly of May 19, 1999, in which additionally a very quotable qualification is added to the comparison:

“He was not just “the voice of a generation,” he was someone whose words lodged themselves in the heads of his contemporaries like shrapnel and remained there for decades afterward.”

Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening” from 1938 consists of four-line couplets in the rhyme scheme abcb, exactly the same as Dylan’s “As I Went Out One Morning”. That is still a fairly classical ballad structure, but remarkably enough Dylan also copies the rather unusual metric pattern: in both works the lines of verse end alternately with a iamb and a trochee.

In terms of content, there is only a superficial similarity. An I-narrator tells about a chance encounter with a stranger, and in both poems there is an amorous tension – here the similarity ends. Auden’s poem is in fact an allegorical narrative, in which the narrator accidentally overhears a conversation, a conversation between Love and Time about the power of love, about the issue of whether Love can resist eternity.

Dylan’s two major themes, Love Fades and Time Passes, as is semi-scientifically established by Watson, the talking computer from IBM in the amusing commercial in October 2015.

But not in his own “As I Went Out Of Morning”. Neither one of the two Great Themes can be distilled from these lyrics, nor any other basic idea. The rather plotless text suggests that Dylan the Poet departed from the same starting point as “Dear Landlord”:

“Dear Landlord was really just the first line. I woke up one morning with the words on my mind. Then I just figured, what else can I put to it?”

(from the Biograph booklet, 1985)

… and this time Dylan wakes up with an echo from W.H. Auden’s poem on his mind. For the continuation, for the what-else-can-put-to-it part, it seems that an everyday, domestic scene seems to urge itself upon the poet: he has brought his daughter to the bus stop and on the way back stops by for a cup of coffee at a friendly neighbour. And is then attacked by the dog, something like that.

The narrator walks into the neighbour’s yard, where the dog is chained – the fairest damsel in chains. Animal lover as he is, he extends his hand to pet, but the bitch immediately snatches and has grabbed the arm of the careless walker – I offered her my hand, she took me by the arm, she meant to do me harm. “Let go, stupid animal, depart from me this moment, bad dog!” he shouts, startled, but that is not going to happen – I don’t wish to. The dog is holding on and growling. Almost begging, the narrator now thinks he hears, it seems as if the dog is unhappy and asks if she can go with him. Fortunately, here comes the owner, running from across the field. He furiously commands his dog to let go of the nice neighbour, commanding her to yield and finally offers his apologies, as it should be. I’m sorry for what she’s done, as every dog owner apologizes for the misconduct of his pet.

Dylan the Poet doesn’t even have to think about how to upgrade such a trivial story. He chooses archaisms like “fairest damsel” and “depart from me” and “I beg you, sir”, he chooses antique, Biblical sentence structure and he chooses a historical, highly loaded name as Tom Paine for the neighbour.

The setup succeeds brilliantly. The ordinary dog-bites-man triviality suddenly is a mysterious, allegorical parable filled with wonderful, poetic power. The Dylanologists are delighted and lose themselves in far-fetched, wide-ranging argumentations to explain what the text “actually” is about. The appearance of “Tom Paine” in particular opens a door that is gratefully trampled down – invariably with references to the scandalous acceptance speech that Dylan gave in ’63 when accepting the Tom Paine Award from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee.

Gary Browning sees criticism of “America’s constitutive myths” and a reckoning with the “legacy of Tom Paine”, without any further explanation (in The Political Art of Bob Dylan, 2004). Bert Cartwright sees “Dylan’s struggle with the Devil” (The Telegraph # 49, summer ’94). And at the basis of all the fiercely digging cryptoanalysts is of course the confused Alan Weberman, who in the July / August issue ’68 of Broadside gets all the space to wriggle, bend and turn over backwards in all the twists he needs to prove that the song is a report of Dylan’s experiences at the 1963 award ceremony:

“Dylan offered them his world view — I offered her my hand. And the leftists wanted to have Dylan as their exclusive possession — She took me by the arm.”

And also the “chronology” – the song being on the album’s first side – is an “clue to the meaning”. In short, it remains puzzling why this Weberman was ever taken seriously by the media.

Incidentally, the dreamlike quality of the song is just as often used to justify failing interpretation – since Lewis Carroll an unsatisfactory, cowardly way out (“Oh, I’ve had such a curious dream!” said Alice).

Then Greil Marcus’ commentary on the song is the most sensible. After an example of a possible but vague interpretation (something related to the unravelling of the American myth) Marcus states that the song offers “possibilities rather than facts, like a statue that is not an expenditure of city funds, but a gateway to a vision.”

The metaphor is a bit crippled, but the underlying thought is worthwhile: Dylan’s texts on John Wesley Harding are not encrypted philosophical tracts, encoded political pamphlets or veiled autobiographical confessions. They are neutral colouring pictures; the lines are drawn and everyone may colour it in as it pleases him. The right colour does not exist. Not “in fact” either.

To a certain extent this also applies to the music. Dylan’s original is breathtaking in its simplicity and naked beauty. Simple melody, stripped-down chord progression and starkly arranged, like all songs on the album.

Hence, a lot of room for the covers.

The South African Tribe After Tribe produces a tight pop song with reggae undertones (on Power, 1985), some restrict themselves to a lonely, solemn piano ballad (Yoni Wolf, 2014), there are derailing, trashy versions, hopping ukulele tunes and dark, gothic readings.

The best covers, however, keep it close to home and choose a country or folk approach.

Mira Billotte’s contribution to the I’m Not There soundtrack, where it is noticeable that drums and bass copy the original almost one-on-one, is quite nice. Just like Dylan, the acoustic Woven Hand limits itself to guitar, bass and percussion, thus proving once again: less is often more.

Yet the unbeatable Thea Gilmore wins again, with a relatively rigged, sometimes power-rocking version on her admirable tribute project John Wesley Harding (2011). The only one who dares to use a harmonica, that’s probably it. And Thea being the fairest damsel, obviously.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 590 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

And “Lily, Rosemary, And The Jack Of Hearts” reminds of Auden’s ‘Victor’ – who stands in the doorway; the Ace of Spades is drawn in the card game.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/36/As-I-Went-Out-One-Morning

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.