by Jochen Markhorst

(This text published 13 Feb 2020 was updated 23 Feb 2020)

“What’s it to ya, Moby Dick?

This is chicken town!”

An opulence of wondrous exuberances, in the sparkling Basement Tapes pearl “Lo And Behold!” and chicken town is just one of many. Thirteen years later, the poultry reference is still intriguing, when John Cooper Clarke, the unaudited court poet of the No Future Generation, also claims to be staying in some Farm Fowl City.

An opulence of wondrous exuberances, in the sparkling Basement Tapes pearl “Lo And Behold!” and chicken town is just one of many. Thirteen years later, the poultry reference is still intriguing, when John Cooper Clarke, the unaudited court poet of the No Future Generation, also claims to be staying in some Farm Fowl City.

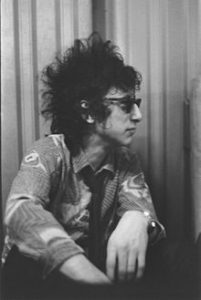

John Cooper Clarke (Salford, 1949) is a British performance poet and when he puts on his sunglasses, he is a cross between the young Dylan and Ronnie Wood. There are more matches with Dylan: his poetic vein and a compelling talent to articulate his poetry rhythmically and melodically. Other comparisons fall short. Musically Cooper Clarke prefers to be accompanied by bare, driving percussion, sometimes a bass line, occasionally a few stray piano chords or some industrial guitar violence. And the catalog is completely incomparable: the Brit records four albums between 1978 and ’82, and that is it. He continues to perform, to this day, but rarely chooses to be accompanied musically.

His pièce de résistance is the 1980 thunderous poem “Evidently Chickentown”, a rhythmic barrage of profane despair, where every verse ends with the despondent observation that the protagonist still is trapped in Chicken Town:

The bloody cops are bloody keen

To bloody keep it bloody clean

The bloody chief’s a bloody swine

Who bloody draws a bloody line

At bloody fun and bloody games

The bloody kids he bloody blames

Are nowhere to be bloody found

Anywhere in chicken town

The poem is, very Dylanesque, an appropriation, directly derived from “Bloody Orkney”:

This bloody town’s a bloody cuss

No bloody trains, no bloody bus,

And no one cares for bloody us

In bloody Orkney.

The bloody roads are bloody bad,

The bloody folks are bloody mad,

They’d make the brightest bloody sad,

In bloody Orkney.

… a wartime poem said to be written by serviceman Captain Hamish Blair, who was stationed in Orkney in World War II.

John Cooper Clarke’s “Evidently Chickentown” has already survived the twentieth century. It continues to show up in documentaries about Thatcher’s England, in films (for example in Anton Corbijn’s Control, on the tragic life of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis) and even in American TV series – over the credits of a Sopranos episode in 2007, for example.

Recurring in the praises and the re-emerging discussions about the work, is the question: what could this Chicken Town be? The always active and ever-expanding Dylan blogs and Dylan interpreters cannot solve this question satisfactorily. Even Greil Marcus carefully avoids an interpretation of this city name for twenty-four pages (the “Time Is Longer Than Rope” chapter in his Invisible Republic is a wildly fanning essay about “Lo And Behold”) but the Cooper admirers can not work it out either.

Contextually, the work does not give a hint, and anyway, a clue will not be there either; an unleashed Dylan here indulges in a frisky, jumpy association game, without worrying about something as irrelevant as intrinsic logic or even a thin storyline. He picked up Chicken Town somewhere – perhaps from fellow countryman Joseph Kalar (1906-1972), the proletarian poet who, like Dylan, was born and raised on the Iron Range in Minnesota. His nickname Rimbaud from the Northern Woods is not entirely conclusive, but will have attracted Dylan as much as Kalar’s unmistakably Woody Guthrie-like appearance, hobo past and workers’ heart. His prose, particularly his “proletarian sketches”, captures the idiom and dialect of the miners and has a similar poetic power and beauty that we hear in Dylan’s Chronicles. In it, in those prose sketches, we also repeatedly come across descriptions of Chicken Town, apparently a (nickname for a) neighbourhood in the mining town of Merritt – for example in the Mesaba Impression “Dust of Iron Ore”, a fascinating sketch of miner’s life during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

It’s just a detail, this chicken town, one of the less noticeable ones even. Dylan weaves around it myriadic, multi-coloured concoctions of half-familiar snippets of text and turbid references. Scraps like I hung my head in shame and syntax like An’ boys, I sure was slick come from the country idiom, and phrases such as Round that horn or Gonna thread up do sound quite authentic, but are catachreses, “abusio’s”, familiar sounding word-play with expressions. To pick up the thread is a template, for example. Round the Horn is actually a nautical concept; the rounding of Cape Horn. Here, through the combination with the equally nonsensical ride that herd, the association is a departure signal (“sound the horn”, “round up”, something like that).

Similarly, the chorus Lo and behold does sound Biblical, but this specific word combination does not occur in the Bible. Genesis 15:3 is the closest thing to it (And Abram said, Behold, to me thou hast given no seed: and, lo, one born in my house is mine heir).

The Bible translation is from 1611, and somewhere in the eighteenth century the expression lo and behold penetrates the vocabulary of the upper circles. Apparently, it becomes a chic way to express wonder or elation. As appears from a 1808 letter from Queen Victoria’s Lady Of The Bedchamber, Lady Sarah Spencer Lyttelton:

Hartington… had just told us how hard he had worked all the morning… when, lo and behold! M. Deshayes himself appeared.

Half a century older (July 22, 1766) is a letter from an anonymised Lady to actor and playwright Thomas Hull:

Here was I sat down, full of Love and Respect to write my dearest Friends a dutiful and loving letter, when lo, and behold! I was made happy by the receipt of yours.

But already at the beginning of the nineteenth century it has become archaic and is really only used ironically. To humorously pretend surprise at an obviousness, for example, or to comment a disappointing revelation.

And, remarkably, it does pop up one time in the English translation of Proust’s masterpiece À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu:

“The doorknob of my room, which was different to me from all the other doorknobs in the world, inasmuch as it seemed to move of its own accord and without my having to turn it, so unconscious had its manipulation become – lo and behold, it was now an astral body for Golo.”

… ironically again. Due to the translator, though. In the source text there is nothing coming close to that Biblical exclamation.

No, the most likely source for the poet Dylan is at home on the bookshelf in the nursery: Grimm’s Fairy Tales, in Edgar Taylor’s translation. Chapter 25, “Rumpelstiltskin”:

Round about, round about,

Lo and behold!

Reel away, reel away,

Straw into gold!

… the song that strange hobgoblin sings as he spins straw into gold.

All in all, it colours the changing moods of the protagonist in Dylan’s song, evidently a fairly young man undertaking quite a journey. From an unknown point of departure he goes to San Antonio, he passes through Pittsburgh (so geographically the point of departure could be West Saugerties, from the Big Pink) and from there it is still more than 2400 kilometres, 1500 miles. But after about a thousand kilometres, he is stranded in Tennessee and eventually does return to Pittsburgh – our hero travels a few thousand kilometres in four verses. If he really wants to do all of that by train (although “coachman” may also mean, very old-fashioned, stagecoach driver), he must either transfer endlessly or make a detour, via Chicago, losing at least three days.

Along the way he meets Moby Dick, decides to purchase a herd of moose (of the kind that can fly, some distant family of Rudolf with his red nose, presumably) and he travels a bit with a Ferris wheel – absolute tosh.

But: it does sow a seed. And the men of The Band are fertilised. The echoes of songs such as “Odds And Ends”, “Tiny Montgomery” or “Please Mrs. Henry” can all be heard in Music From The Big Pink and “Lo And Behold! ” seems to descend into the brilliant showpiece of that album, into “The Weight”.

Robbie Robertson himself points to personal life experiences, to Levon Helm and the films of Luis Buñuel, but it is very unlikely that the modern classic “The Weight” (Take a load off Annie) could have been conceived without “Lo And Behold!”:

I pulled into Nazareth,

I was feelin’ about half past dead

I just need some place

where I can lay my head

… is undeniably an echo from Dylan’s

I come into Pittsburgh

At six-thirty flat.

I found myself a vacant seat

An’ I put down my hat.

In his autobiography This Wheel’s On Fire (1993), Levon Helm also mentions “The Weight” as one of the songs “we brought down from Big Pink” and he remembers:

“The funny thing was, when Capitol sent out a blank-label acetate of Big Pink to press and radio people, everyone assumed “The Weight” was the Dylan song on the album. The Band fooled everyone except themselves.”

The humbug of “Lo And Behold!” works – unintented – all the more comically in the covers that tackle the song with bloodless seriousness (Invisible Republic is a good example), or, less comically, the humourless, toe-curling artists who try to put some pathos in the meaningless bullshit. Tribute bands often fall into that trap, and of the more ambitious artists, B-actor Marjoe Gortner is a high / low point on the LP Bad But Not Evil – although according to Billboard at the time (1972) it was a “strong debut” of a “hot film star”.

The positive exception is, again, the version of Coulson, Dean, McGuinnes, Flint on perhaps the most beautiful Dylan covers album ever, Lo And Behold from 1972. The furry British quartet excels under the direction of producer Manfred Mann, the hit-sensitive master musician who himself is already one of the best Dylan interpreters. Pure rock ‘n’ roll, indeed – sounding something like Lou Reed’s “Vicious” performed by Bad Company – and yet almost as irresistible, uplifting as the original.

But in the end, Dylan’s original with The Band is only matched by the take 1 that we get to know thanks to The Basement Tapes Complete. The first recording sets in even more deadpan, but Dylan loses his cool; after the third verse almost collapsing into guffaws. And a little later again. An’ boy, he sure is slick.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 594 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews