By Jochen Markhorst

On March 8, Tony posted here on Untold “Desolation Row – The Origins of the Title”. That was Chapter 1 of my attempt to write an article about “Desolation Row”, which got a bit out of control. It led to a 17-chapter book (available on Amazon). We will still post some chapters here, though. Below a second contribution: Chapter 6, on the Ophelia-stanza.

As Tears Go By

Now Ophelia, she’s ’neath the window

Now Ophelia, she’s ’neath the window

For her I feel so afraid

On her twenty-second birthday

She already is an old maid

To her, death is quite romantic

She wears an iron vest

Her profession’s her religion

Her sin is her lifelessness

And though her eyes are fixed upon

Noah’s great rainbow

She spends her time peeking

Into Desolation Row

I Stompin’ At The Savoy

A work of art like “Desolation Row” stands on its own, but yet… the promise “to sketch You a picture of what goes on around here sometimes” (liner notes Bringing It All Back Home) is a tempting incentive to browse around Dylan’s environment in the months prior to the completion of the monument. Not so much to “crack codes” or to find out what the words “actually” mean, but because it offers mere mortals a chance; a chance to gain some insight into the method, or the inspiration, or the perception of a poetic genius.

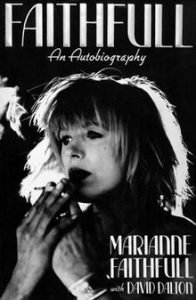

Marianne Faithfull, in her grandiose memoirs Faithfull; An Autobiography (1994), lifts an intriguing corner of the veil:

“For days I had been told that Bob ‘was working on something.’ I asked what (I was meant to ask). ‘It’s a poem. An epic! About you.’ Why bless his heart, I thought, he’s hung up too! But you don’t ever quite know with Bob; he wears his heart very close to his vest. No one was ever such a seducer as Dylan.”

This is early May 1965; in the eight or nine days that Faithfull hangs out in Dylan’s suite at the Savoy Hotel. The first recording of “Desolation Row” takes place on July 29 and the only other candidate for a “poem about you” with “epic” qualities is “Like A Rolling Stone”, which according to Dylan was distilled from a poem of ten pages long (or twenty, according to a radio interview in Montreal ’66, or six, as he says in Shelton’s No Direction Home).

The fairylike, elusive and seemingly timid Faithfull is indeed a perfectly fitting, lifelike model for the Miss Lonely who went to the finest schools. In addition to all other exceptional qualities, “Like A Rolling Stone” would then also have a prophetic value:

Once upon a time you dressed so fine

You threw the bums a dime in your prime, didn’t you?

People’d call, say, “Beware doll, you’re bound to fall”

You thought they were all kiddin’ you

You used to laugh about

Everybody that was hangin’ out

Now you don’t talk so loud

Now you don’t seem so proud

About having to be scrounging for your next meal

… almost every letter of the legendary opening couplet being perfectly applicable five years later to the bizarre fate of Marianne, who indeed goes from riches to rags, ends up in the gutter, is homeless for a while, and freeloading and scraping up her food, shelter and drugs.

But this striking resemblance Faithfull also has to the Ophelia from the fourth verse of “Desolation Row”.

She idolizes Dylan, this spring of ’65. He is “the hippest person on earth”, and when “God Himself” checks into the Savoy on April 26, 1965, she just has to go there.

She idolizes Dylan, this spring of ’65. He is “the hippest person on earth”, and when “God Himself” checks into the Savoy on April 26, 1965, she just has to go there.

The timing is lousy. The then eighteen-year-old has just discovered she is pregnant and in ten days she will marry the father, the unfortunate John Dunbar. But at this moment Dunbar is still in Cambridge for a few more days, and the impulsive teenager, who for most of her life has a particularly poor resistance to temptations, does go. So I went to see the gypsy, as she writes with a superb sense of irony. (The writer is infectiously prone to the dosed use of unobtrusive Dylan references. She has difficulty with the fog-and-amphetamine factor of producer Andrew Loog Oldham, to name but one nice example).

She is already an arrivée, has already had Top 10 hits (with “As Tears Go By” and “Come And Stay With Me”) and therefore has little trouble penetrating the inner sanctum. But in there she is again the blue, uncertain ingénue. Those few flashes from Marianne in Don’t Look Back, curled up in a chair in the corner, staring swooningly at Dylan, do match her own recollection; she keeps quiet, especially for fear of making a fool of herself. “I mean, what if I said something really stupid? The gates of Eden would be closed forever.” And also somewhat intimidated by the presence and beauty and talent of Joan Baez, by the way – who, according to Marianne, plays a breath-taking version of “As Tears Go By”. “I’ve never heard it sound better,” she says, adding with superior irony: “not even by whatsisname,” both a self-mocking reference to former partner Mick Jagger and a nod to one of the horrible films in which she plays in those years, I’ll Never Forget What’s’is Name (1967). In which she does write film history, as a matter of fact: she is the first actor to use the word fuck in a movie.

II To be Ophelia (or not)

Being timid and curled up in a corner, however, draws the attention of the Bard, according to the chapter “What’s A Sweetheart Like You Doing In A Place Like This”. La Faithfull tells how he makes advances that she does not recognize as such, upon which he furiously blames her for playing games. Her astonished sputtering that she is pregnant and is getting married next week, turns Dylan into a frantic Rumpelstiltskin, tearing up a sheaf of papers in a tantrum like a furious child: “Are you satisfied now?!”

Marianne suspects that the pile of paper was the “epic poem” he supposedly wrote for her.

A far more attractive option is that impressions of Faithfull have nevertheless swirled down in lyrics. Maybe in “Like A Rolling Stone”, but the Ophelia couplet in Desolation is just as strong a contender.

Marianne does have an Ophelia-like aura and describes in her memoirs how she herself identifies with exactly this tragic heroine:

“For years I had been babbling about death in interviews. That was playacting. There came a time, however, that it stopped being a performance. The combined effect of playing Ophelia and doing heroin induced a morbid frame of mind – to say the least – and I began contemplating drowning myself in the Thames. I was acting as a child does. I had fused with my part…. I would indulge myself in lurid pre-Raphaelite fantasies of floating down the Thames with a garland of flowers around my head.”

Dylan and Faithfull herself are not the only ones who see an Ophelia in the fragile beauty, in the aristocratic, blonde Mona Lisa. Director Tony Richardson offers her the role in 1968, first in the stage performance and then in the film adaptation (1969) of Hamlet. Coincidentally, she really is an Ophelia on her twenty-second birthday (Marianne does indeed turn twenty-two on December 29, 1968, during the stage performances and just before the film version of Hamlet).

It is not an undisputed choice. The critics are divided. Time Magazine is poetic and downright positive (“remarkably affecting… ethereal, vulnerable, and in some strange way purer than the infancy of truth”), but most reviews are less flattering. The general tenor is: stoned hippie girl, empty-headed sex object.

Hindsight and Marianne’s own report do support the harsh critique. We don’t see Ophelia, but we continue to see Faithfull, childish and erotic at the same time, bordering on awkwardness, even – her first scene (Act I, scene 3) is with brother Laërtes, who does not seem to warn her of Hamlet, but of men like Dylan and Jagger:

Weigh what loss your honor may sustain

If with too credent ear you list his songs,

Or lose your heart, or your chaste treasure open

To his unmastered importunity.

… watch out for that horny guy who makes your head spin with his beautiful songs, so that you will lose your chastity and respectability. But in the meantime, Marianne’s / Ophelia’s tightened breasts are almost bulging out of her cut dress and she kisses her brother for a long time on the (open) mouth, giving the whole scene an unprecedented and incestuous charge unforeseen by Shakespeare.

Both during the plays and during the filming, Faithfull is often high, in between acts she has sex in the dressing room with protagonist Nicol Williamson, and otherwise with the drug dealer of the Stones, Tony Sanchez, thus paying him for heroin. She later regrets that quite a bit, and she shares with us a dubious life lesson she learned from it, in which she again squeezes in a Dylan reference:

“I never had any cash. I now realize that if you do want drugs, then you have to make your own money and buy them! To live outside the law you must be honest, but I didn’t understand that yet. For years I simply charmed and seduced people to get what I wanted.”

She sometimes plays the madness scene right after she has used heroin. “It might even have helped in some perverse way,” she admits in her other autobiography, in Memories, Dreams And Reflections (2008).

It explains, all in all, the detached, hazy appearance, that look as if she sees Noah’s great rainbow, but at the same time the closeness of the abyss, the peeping into the desolate back-alley, the peeking into Desolation Row.

III Faithfull revisited

With the same benefit of hindsight, it seems that the artist Dylan, in the spring of 1965, sketches the future of the girl who is curled up in a chair next to him in the hotel room. One scene can even be found one-on-one in Faithfull’s book. The opening Ophelia, she’s ’neath the window seems to be a paraphrase of what Marianne describes as her upcoming groom John Dunbar is waiting for his fiancé down the street, under the window of Dylan’s hotel suite. Naively and clumsily, she reveals that rather embarrassing fact in Dylan’s overpopulated suite, upon which the whole company, Dylan first, rushes to the window to see for whom Marianne has rejected Dylan and to mock him. Dunbar, he’s ’neath the window, for him I feel so afraid.

An old maid is, oddly enough, quite a striking description too. Marianne is only eighteen, but apparently the susceptible, sharply observing Dylan already sees the contours of the old maid she will be in four years’ time, on her twenty-second birthday; a young girl with the life experience of a forty-year-old ex-groupie – with the accompanying, perhaps inevitable, tragedy and decline. An iron vest, the seemingly unapproachability, cuddly but unreachable, is just as recognizable, and even the words that Dylan steals from Jack Kerouac, her sin is her lifelessness, very aptly portray Faithfull’s vacant Ophelia, to whom death is quite romantic.

Fourteen years later, shortly after the release of her come-back album Broken English (1979), the chanteuse tells in the chapter “Dylan Redux” that Dylan visits her completely unexpectedly in London. Badly timed once again of course – Faithfull has just got married to Ben Brierly – and Dylan is cuddly, compellingly vulnerable, swears he has never been able to forget her, and he expresses regret for the incident with the torn poem.

But what was written in the poem we still don’t know.

————————————————

Jochen’s new book has just arrived in the offices and we’ll be reviewing that shortly.

Jochen’s new book has just arrived in the offices and we’ll be reviewing that shortly.

It’s available in English and in Dutch, both as a paperback and on Kindle.

Details are on the UK Amazon site, or of course on the Amazon site for your country.

Just search for “Desolation Row” by Joch Markhorst.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 595 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

Fascinating.

Interesting book, interesting information about Marianne Faithful and Bob Dylan. Thank you.

But I have to protest. You call Marianne Faithful a groupie. She was an actor and singer just like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez and Mick Jagger. Unfortunately the heroine was addicted to heroin, which ruined her life for a period.

I think Bob Dylan bully those great female singers and models, who got addicted to drugs and ended up on the street and to whom he has had a close relationship. I hate him for that. “Like a rolling stone” is another example. The song is so mean, cruel and inhuman. Everybody sing along, but they don´t know the tragic stories behind. It is stories about drug addiction, free sex, and sometimes pregnancies, abortions and adoptions of the children. Sorry to say: Maternity ward must have had a busy time. Bobs future wife got pregnant at the same time!!! He had himself a heroin abuse. He was lucky that the Lady of the Lowlands accepted to help him.

Let Marianne Faithful sing Yesterday for you. She was a great singer. I was 10 years old. Unforgettable even though I had no clue, what is was about.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gORyrU1xQpg

Merci Babette – and let me reassure you: I most certainly do not call La Faithfull a groupie. I merely tried to express what Dylan might be seeing as he sees the silent, swooning Marianne sitting there, curled up in a chair in the corner of his hotel room. As for me, I am far too infatuated with Marianne Faithfull to ever disqualify her. Plus, my mother would not forgive me.

As for your observations regarding background and Dylan’s alleged meanness: you seem convinced, as the vast majority of Dylan followers seems to be, that Dylan’s songs are encrypted, veiled outpourings, or anecdotes, or opinions, or whatever, from the man Dylan himself, revealing intimate feelings or private incidents from his personal life. Apart from being very petty, this seems very unlikely to me, as it is very unlikely at any great artist. But “La chanson est si peu souvent l’oeuvre, c’est-à-dire la pensée chantée et comprise du chanteur”, as Rimbaud said.

And, with Rimbaud, Dylan himself tries to assure you, for more than 50 years now, that je est un autre, but to no avail, apparently. You, and with you quite a lot Dylan aficionado’s, insist on seeing his songs as rather petty, personal reckonings. I see and read convictions like yours everywhere, writers trying to proof that a ‘she’ in one song is “actually” Sara, and a ‘her’ in another song is “actually” Joan, and a ‘baby’ in a third song is “actually” Edie, and that the ‘I’ in every song is “of course” Dylan himself.

I really don’t think Dylan, as any true artist, is that small-minded. I prefer to think Dylan’s poetry is so much richer, deeper and more universal than that. To me it is, anyway.

Now I smile. We agree about Marianne Faithful. What can I say about Rimbaud. An extremely intelligent young boy, gay, son of a captain. Not an easy puzzle at that time. He ran away an lived a chaotic life with Verlaine. They disturbed their senses with absinth and hash and wrote all their thoughts down. Fragmented sentences. Paranoid hallucinations. Detached from reality. Also a life with violence and loss of control. Of cause there must have been some bright thoughts. During my work as a doctor I have talked with many patients with drug or alcohol psychosis and patients with manic psychosis. I don’t find it very interesting. I know Dylan likes those poets, but his poems are much more structured and with a meaning. His images are not chaotic. He has an idea with the poem. Often he uses characters from the literature, the history or the mythology to illustrate, what you call the universal, but it does not mean that everything is fiction or coming out of the blue air. I do understand if Bob Dylan wont explain it, and I respect you are satisfied with the images and symbols. Phenomenological interpretation. Smile.