by Jochen Markhorst

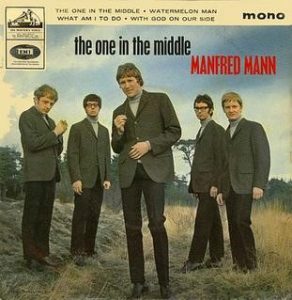

“With God On Our Side” is the first Dylan song Manfred Mann takes a shot at and can be found on the 1965 EP The One In The Middle. The EP is a huge hit; achieves first place in the EP charts three times and sells so well that it also scores in the singles Top 10.

“With God On Our Side” is the first Dylan song Manfred Mann takes a shot at and can be found on the 1965 EP The One In The Middle. The EP is a huge hit; achieves first place in the EP charts three times and sells so well that it also scores in the singles Top 10.

The title song is really nice, and with the other songs (the jazzy “Watermelon Man” and the Phil Spector/Doc Pomus ballad “What Am I To Do”) is not much wrong either, but the Dylan cover is the real highlight. The song is recorded, according to the liner notes, because Dylan had attended a live concert of the band, after which he declared the band being “real groovy”.

Dylan suits Manfred. After this, the band makes a sparkling adaptation of “If You Gotta Go, Go Now”, which becomes a huge hit too. Manfred’s Dylan love gets an extra boost when Dylan publicly declares, at a press conference in December 1965, that nobody does as much justice to his songs as Manfred Mann: “They’ve done about three or four. Each one of them has been right in context with what the song was all about.”

Not entirely correct (Mann only recorded two Dylan songs at that time), but that can’t spoil the glorious feeling. For his book Jingle Jangle Morning: The Folk Rock In The 1960s Richie Unterberger asks Manfred what he thought of that public approval. “It certainly didn’t depress me when I read that. I was delighted, of course.”

This retrospect is spoken in 2014 after Manfred has recorded some twenty Dylan songs. In the ’60s, still leading his eponymous beat group, he elevates “The Mighty Quinn (Quinn The Eskimo)” to a world hit and to the pop monument it still is today, shortly after he conquered the charts with “Just Like A Woman” as well. And had a big hit with one of the most successful Dylan rip-offs of the ’60s, the catchy psych-pop gem “Semi-Detached Suburban Mr James”, which originally sings a Mr Jones by the way. Because singer Paul Jones has just left the band (this is the first hit with new singer Mike d’Abo), Manfred imagines that a song about a Mr Jones with phrases like So you think you will be happy, taking doggie for a walk and Do you think you will be happy, giving up your friends, might be conceived as a kick after he’s down, so he last-minute changes Jones into James.

In 1971 Mann starts his Earth Band and continues the tradition; for almost every album in the 70’s he records a Dylan cover. Still with the master’s consent, apparently. When a journalist at a press conference in Travemünde in 1981 asks Dylan what he thinks of Manfred Mann’s covers, he answers: “Yeah, those are okay… even better than Peter, Paul And Mary.”

The success of “Quinn The Eskimo” points Mann to a fertile side-path: the under-appreciated ditties, the shelf warmers, the ugly ducklings and the wallflowers. Manfred turns out to be a true master in the cutting of rough diamonds, in the development of fallow land – more or less as Dylan himself does, with forgotten songs and dusty melodies and from past centuries.

A first structural start is made by Mann as a producer, for the hairy quartet Coulson, Dean, McGuinness, Flint.

When Gallagher and Lyle leave the band McGuinness Flint after two albums and as many hits (“When I’m Dead And Gone” and “Malt And Barley Blues”) in 1971, the remaining band members not only lose two very talented multi-instrumentalists, but also the most important songwriters.

McGuinness complains to his old bandleader Manfred Mann, who knows what to do. Bass player Dixie Dean is called in, McGuinness has a pile of unknown Dylan songs lying around (thanks to a friend at music publishing company B. Feldman & Co), Manfred takes his place behind the recording desk and the organ and then the men throw themselves onto Basement gems like “Please Mrs Henry” and “Sign Of The Cross”, onto a few unreleased early Dylan songs, and onto curiosities like “Eternal Circle” and “I Wanna Be Your Lover”.

The artistic success of the resulting masterpiece Lo And Behold! (1972) shows Manfred Mann the way to the hits he will make in the ’70s with overlooked Dylan songs, to shining covers of less appealing songs like “Quit Your Lowdown Ways”, “You Angel You” and “Father Of Day”.

The first album of his Earth Band, Stepping Sideways, will never be officially released, but in the twenty-first century, thanks to a Biograph-like box (Odds And Sodds – Mis-takes And Out-takes, 2005), we do get to know the “Please Mrs Henry” he recorded for it. For the first official album (Manfred Mann’s Earth Band, 1972) the band records a radically different, but equally brilliant version of that ignored Basement song.

The album flops, but Mann never despairs. Side Two of Messin’ (1973) opens with yet another wonderful version of yet another unknown Dylan original, “Get Your Rocks Off!”, again a remnant of those basement sessions in the Big Pink. For the American market, Messin’ is renamed Get Your Rocks Off! and given a different, quite ugly album cover. To no avail; the album doesn’t get any further than the 196th place on the Billboard 200 (June 1973, the same week George Harrison’s forgotten masterpiece Living In The Material World is number one).

The original of “Get Your Rocks Off” harvests little affection with the professional Dylanologists. Clinton Heylin considers it a “perversity” that this song was, and songs like “Going To Acapulco” were not immediately copyrighted, stating that this “least successful” song isn’t much more than some fiddling around the double entendre of rocks (the rocks to stone someone, on the one hand, the vulgar name for testicles on the other hand). Cultural Pope Greil Marcus virtually ignores the song in his exuberant declaration of love to the Basement Tapes, in Invisible Republic (1997), merely mentioning it as one of the examples of the miasmic, unplaced, floating dramas. The qualification miasmic in particular is rather puzzling; “toxic smell producing, noxious, disgusting”? An enigmatic, but anyhow not too charming designation.

Similarly, in echelons below, with respected amateur Dylanologists like Tony Attwood, there is little love to be found. Attwood listens to the song on The Basement Tapes double-cd-edition, finds the best about the song: that “Santa Fe” comes after it, and does not understand why the song gets a place on an album at all.

The other extreme is the venerable emeritus professor Louis Renza in his Dylan’s Autobiography of a Vocation (2017), which tries, bordering on awkwardness, to expose depths in the jovial party song. The “explicit allusion to Blueberry Hill and the image of the bus cruising down the highway conjure the rock ‘n’ roll demand of touring,” still is a naïve, charming interpretation by the professor and Dylan scholar from the stately Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Arriving at the mysterious Mink Muscle Creek, though, Prof. Renza really goes berserk:

“Dylan points to himself and another man “layin’ down around Mink Muscle Creek,” a scene keynoted by two tropes: commercialized “mink” a.k.a. the money and social status that come with rock ‘n’ roll success; and the power (“muscle”) a celebrity figure like Bob Dylan unavoidably feels he can wield in his (then) cultural environment. Both threaten to block Dylan’s already weakened (it being merely a “creek”) flow of creativity and for him its indissociable relation to his existential vision.”

Fancy words, eventually leading to the conclusion of how Dylan in this song, roughly like in “Maggie’s Farm”, exhibits his annoyance about his audience’s expectations and the demands made on him. So: “Get those heavy stones off me, relieve me of this burden.”

Renza ignores, probably out of ambition, the most obvious analysis: the playful language artist Dylan, who, as is often the case, is mainly guided by the sound of the words and less, or even not at all, by their semantic charge. After all, more important than the content is the sound, as Dylan noted in that Playboy interview with Rosenbaum in 1977. And “Mink Muscle Creek” (or “Mink Mussel Creek” or, even more trite, “Mid-muscle Creek”) sounds great, runs like clockwork. The poet doesn’t care so much about the content. In fact: it amuses him quite a bit, as we can hear from the master’s infectious, squealing laughter during the recording session.

Which should have warned Renza against taking this all too seriously. Or else Robertson’s testimony from Testimony:

“We marched back down into our subterranean refuge and recorded “Get Your Rocks Off”. Garth played some killer organ on this one. Bob could usually get through his hilarious lyrics, but after he sang “mid-muscle creek,” he cracked up, couldn’t hold it in any longer. Richard’s bass vocal raised the stakes – “Get ’em off!” Great fun, great mood.”

Apart from this: in general, Professor Renza certainly deserves every admiration for his missionary work, for his efforts to make Dylan penetrate the highest academic circles. In the end, he is certainly one of the trailblazers for Dylan’s Nobel Prize.

The lazy, languid original is already pretty much polished up by Coulson, Dean, McGuinness, Flint, who turn it into a dry, cool stomping, funky swamp blues with a sultry Lynyrd Skynyrd-like turn-over halfway through. Producer Manfred Mann apparently couldn’t let go of the song and then pours even more concrete on “Get Your Rocks Off!” with his Earth Band. It’s a driving, sweaty hard rocker and after “Mighty Quinn” and “Please Mrs Henry” the third basement-scribble Mann manages to pimp up into a beautiful Dylan song.

The secret is, Mann explains to Unterberger: disrespect. That is essential.

“We had the songs that everyone else had missed, where the original versions were sometimes quite idiosyncratic and a bit left-field. But I could use it. I was simply a bit of a predator, looking for material.”

Material from which some are building monuments – the phenomenon Manfred Sepse Lubinowitz from Johannesburg most certainly does, in any case.

The English version of Jochen’s “Basement Tapes” book is now available on Amazon, though Amazon seems to have delivery problems at the moment, as in some parts of the world you may find the disappointing introduction “Currently unavailable for delivery to your region due to high demand. We are working to resume delivery as soon as possible.”

There is a review of the book at here which the publisher of this august journal is willing to mention despite being called an “amateur Dylanologist” in the piece above.

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with approaching 5000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/209/Get-Your-Rocks-Off

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.