by Jochen Markhorst

Like earlier “Desolation Row” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, “Mississippi” can’t really be dealt with in one article. Too grand, too majestic, too monumental. And, of course, such an extraordinary masterpiece deserves more than one paltry article. As the master says (not about “Mississippi”, but about bluegrass, in the New York Times interview of June 2020): Its’s mysterious and deep rooted and you almost have to be born playing it. […] It’s harmonic and meditative, but it’s out for blood.

This article continues from

- Mississippi, part I; no polyrhythm here please

- Mississippi, part 2: the line that never was.

- Mississippi part 3: Belshazzar on the steppe

IV Bertolt, Bobby, Blind & Boy

City’s just a jungle; more games to play

Trapped in the heart of it, tryin’ to get away

I was raised in the country, I been workin’ in the town

I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down

Bertolt Brecht is quite proud of himself. On September 4, 1921, he writes in his diary about his “groundbreaking discovery”,

Bertolt Brecht is quite proud of himself. On September 4, 1921, he writes in his diary about his “groundbreaking discovery”,

“that actually no one has ever described the big city as a jungle. Where are their heroes, their colonizers, their victims? The hostility of the great city, its malicious stone consistency, its Babylonian confusion of languages, in short: its poetry is not yet created.”

In the same weeks, Brecht writes Im Dickicht der Städte (“In the Jungle of Cities”), a dizzying piece in which Brecht is not too concerned about a logical plot or understandable motives, but shows different stages of a catastrophic quarrel between two men. With a vague, homoerotic undertone, so some like to see a dramatic portrayal of a Rimbaud-and-Verlaine-like relationship, but the main theme is: loneliness – extra sharp-edged because the men, despite being in the big, busy city of Chicago, are actually mostly lonely. Most disconsolate expressed by the timber merchant Shlink: “The infinite loneliness of man makes enmity an unattainable goal.”

By the way, Brecht’s complacent diary entry is yet another fine example of the great playwright’s Love & Theft – earlier in his diaries he explains his admiration for Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1905), the social-realist novel that compares the city – not coincidentally also Chicago – to a jungle.

By the time Dylan writes “Mississippi”, jungle as a metaphor for “big city” is long established. Not only in books, newspapers and films, but also in songs. Songs that are also in Dylan’s record cabinet, anyway. Bobby Darin, for instance.

The 1968 album Born Walden Robert Cassotto marks a rather radical career break for Bobby Darin. He leaves his record label, writes all the songs himself and converts to folk rock, sociocritical lyrics and an unpolished singing style, much more unpolished than the crooning style which made him great. One of the songs, “Long Line Rider”, even causes some controversy, which gets him attention from folk magazine Broadside.

In the 1969 March/April issue Dylan’s old comrades and doormats print an article from the New York Post of February 1: “Censored Darin Sings a Song of Protest”. The controversy is painfully petty by today’s standards. In the song Darin expresses his amazement at an alleged cover-up operation after the discovery of some unidentified skeletons on a prison site. Remarkably smooth investigation concludes that the corpses were buried there before there was any prison at all, and Darin raises suggestive questions:

All the records show so clear Not a single man was here Anyway Anyway. That's the tale the warden tells As he counts his empty shells By the day By the day. Hey, long line rider, turn away.

Just before a television performance (The Jackie Gleason Show, January ’69) record company CBS sends a telegram with the order to delete the above words. Enraged Darin walks out, a scandal seems unavoidable, but it doesn’t really get off the ground.

The song and the story behind it have long since been forgotten, but the flop album itself stands the test of time; it’s a beautiful album with beautiful songs (“I Can See The Wind”, especially, the Leonard Cohen rip-off “In Memoriam” and the Moby Grape-like “Change”). However, style, change of course and the level of protest are not the only indications that Darin is trying to level his idol Dylan. He’s already recorded some successful Dylan covers, will record even more beautiful ones in the coming years (his “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is one of the most successful covers of that evergreen), and on this record Dylan’s influence is evident from the lyrics Darin writes:

We live in a jingle jangle jungle You're only worth what you can buy So keep on workin' hard To keep your own back yard Teach your kids that God Ain't fiction Contradiction In this jingle jangle jungle you call home.

Dylan undoubtedly knows the record and the song, but jungle as a metaphor for the big city is more likely to have come to him through Phil Ochs’ “Lou Marsh” (or Pete Seeger’s version thereof):

Now the streets are empty, now the streets are dark So keep an eye on shadows and never pass the park For the city is a jungle when the law is out of sight Death lurks in El Barrio with the orphans of the night

“The city is a jungle when the law is out of sight”… the image plus the words that match the opening of Dylan’s “Mississippi”, the opening verses that poetically introduce the oppression, hopelessness and anguish of the protagonist.

After the sixth verse, the accumulatio, the accumulation of the equivalents all expressing approximately the same claustrophobic, Kafkaesque distress, seems to come to an end, and the plot can unfold:

I was raised in the country, I been workin’ in the town I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down

… promising a novel-like plot. The trouble, the drastic event in the main character’s life is coming up. A first character description is also given: boy from the countryside, who has to make a living in the metropolitan jungle – and it don’t come easy, as evidenced by the beautiful, lyrical suitcase line.

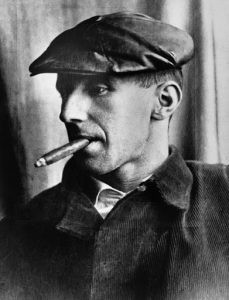

It’s one of the most beautiful lines in the song, a line with the shine of a polished, old-fashioned blues cliché, but actually a Dylan original – at best it does echo a hint of Blind Lemon Jefferson, “Easy Rider Blues”:

I went to the depot I mean I went to the depot, set my suitcase down The blues overtake me and the tears come rollin' down

Blind Lemon is a common thread in Dylan’s oeuvre. “See That My Grave Is Kept Clean” on the first record, which pops up again in the Basement as “One Kind Favor”, “High Water Blues” as template for “Down In The Flood”, Blind Lemon’s guitar in Masked & Anonymous, the name checks in interviews and in Chronicles, the attention in Theme Time Radio Hour… it’s likely that such a verse fragment as I set my suitcase down was etched in Dylan’s brain by Blind Lemon. His poetic brille does the rest; connecting the words to I been in trouble since is considerably more powerful (and more poetical) than Blind Lemon’s somewhat stiff continuation.

Apparently Boy George, of all people, thinks so too – in the twenty-first century he lovingly steals it for “Wrong” (on U Can Never B2 Straight, 2002):

I came to the city with my head so full of dreams The city was safe alright but not from me See I've been in trouble since I lay my suitcase down I love the sound of my own voice, but now I want it drowned

… insinuating that he is one of those predators that turn the city into a jungle. Which, given “Boy” George Alan O’Dowd’s reputation, indeed does sound a little more convincing from his mouth than from Dylan’s.

To be continued. Next up: Mississippi part V: Frost in the room, fire in the sky

=============

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a subject line saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 6500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

I tell you now, mama, I’m sure gonna leave this town

‘Cause I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down

(Ishmael Bracey: Leaving This Town)