by Jochen Markhorst

Like the earlier compositions such as “Desolation Row” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, “Mississippi” can’t really be dealt with in one article. Too grand, too majestic, too monumental. And, of course, such an extraordinary masterpiece deserves more than one paltry article. As the master says (not about “Mississippi”, but about bluegrass, in the New York Times interview of June 2020): Its’s mysterious and deep rooted and you almost have to be born playing it. […] It’s harmonic and meditative, but it’s out for blood.

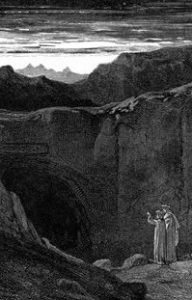

IX Abandon all hope

Walkin’ through the leaves, falling from the trees

Feelin’ like a stranger nobody sees

So many things that we never will undo

I know you’re sorry, I’m sorry too

The opening line of this quatrain is deceptive. At first sight, the setting looks like a clichéd film scene. A melancholy protagonist, strolling in an autumnal forest over the rustling leaf. It is only at second glance one is struck by this atypical falling.

The opening line of this quatrain is deceptive. At first sight, the setting looks like a clichéd film scene. A melancholy protagonist, strolling in an autumnal forest over the rustling leaf. It is only at second glance one is struck by this atypical falling.

The narrator does not walk through fallen leaves, fallen from the trees, but through leaves, falling from the trees. Participium praesens, a present participle: the leaves are falling, while the protagonist walks through them – the protagonist who does feel like an invisible stranger here… suddenly this is very reminiscent of Dante.

“Canto III” from Dante’s Inferno is probably one of the best known. It is the song that tells how Dante and Virgil arrive at the Gates of Hell, at the cheerful welcome sign Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’intrate – “Abandon all hope, ye who enter here” – the closing words which will be re-used by Dylan in 2020 for “Crossing The Rubicon” (I painted my wagon, abandoned all hope and I crossed the Rubicon), just as further verses seem inspired by that same excerpt from the Divina Commedia:

You won’t find any happiness here No happiness or joy

Hell’s vestibule already is an ordeal to Dante. And here are still only the souls of those who have been neither good nor bad – but their screams, the “languages divers, orribili favelle, horrible words” and the “words of agony” frighten Dante. They have to make their way through though, to the “the dismal shore of the Acheron”, the muddy, black, bitter River of Suffering, where ferryman Charon will sail them to the other side, to the underworld.

Dante’s description of Charon, especially Charon’s eyes, suggests that Dylan has browsed the Inferno more than once and more than fleetingly. The first time the ferryman is described is in this song, in verse 82-99. The introduction ends with the remarks that the skipper has “wheels of fire around the eyes”, the title of one of Dylan’s Basement songs from 1967.

The second time is ten lines down:

The dæmon, with eyes like burning coal, - Charon – enrols them, for the passage bound And with his oar goads on each lingering soul

“Eyes like burning coal”, as Wordsworth translates con occhi di bragia seems to echo in “Tangled Up In Blue”:

Then she opened up a book of poems And handed it to me Written by an Italian poet From the thirteenth century And every one of them words rang true And glowed like burnin’ coal

Probably one of the most discussed verses in Dylan’s oeuvre, but on which a kind of consensus has gradually emerged. The obvious candidates for this “Italian poet from the thirteenth century” are the fourteenth-century poets Petrarch, Boccaccio and Dante, and the scales tip towards to Dante (although in ’78 Dylan clouded the waters by answering when asked: “Plutarch. Was that his name?”). However, the ease with which Dylan, in live performances, changes the reference in question to Baudelaire or to Jeremiah does give ground to the theory that the bard has no particular poet in mind at all, but in this verse line, as is often the case, chooses the sound.

Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy, then seems to provide decor, imagery and colour for this quatrain in “Mississippi”. In Chronicles, Dylan in any case parades his memory that he had the book in his hands:

“Sometimes I’d open up a book and see a handwritten note scribbled in the front, like in Machiavelli’s The Prince, there was written, “The spirit of the hustler.” “The cosmopolitan man” was written on the title page in Dante’s Inferno.”

This plays in one of his lodgings, with “Ray and Chloe”, in the time before Dylan recorded his first LP, so around 1960. It seems rather unlikely that the autobiographer Dylan remembers handwritten scribbles in other people’s books more than forty years later, but well alright. In this passage Dylan sums up a whole zip of antique and less antique writers, refers to works that do not exist and remembers fantasised titles – apparently Dylan is not so much striving for academic correctness, but still does feel a need to demonstrate that he is not entirely uneducated.

Anyway – Inferno. After that depressing vestibule Dante and Virgil approach the bank of the Acheron. Charon sees that Dante is still alive and therefore doesn’t want to take him with him, but is overruled by Virgil, who seems to have some authority, down here. Meanwhile, it gets busier and busier on the bank: the souls of the damned, who have to be taken to the other side.

As in the autumn-time the leaves fall off, First one and then another, till the branch Unto the earth surrenders all its spoils; In similar wise the evil seed of Adam Throw themselves from that margin one by one, At signals, as a bird unto its lure.

And thus, Dante is walking through the leaves, falling from the trees, through the wandering souls who can’t see him, to Charon’s ferry. He’s a stranger here, being the only one with a good soul, according to Virgil, among all those souls who never will undo their failed lives. Dante’s sorry. And they are sorry too.

Previously in this series

- The Mississippi-series, part 1; no polyrhythm here please

- The Mississippi-series, part 2: the line that never was.

- Mississippi- series, part 3: Belshazzar on the steppe

- The Mississippi-series, part 4: Bertolt, Bobby, Blind & Boy

- The Mississippi-series, part 5: Frost in the room, fire in the sky

- The Mississippi-series, part 6: Charades

- The Mississippi series: part 7: Dorsey Dixon

- The Mississippi-series, part 8: Pretty Maids All In A Row

To be continued. Next up: Mississippi part X: Eyesight To The Blind

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

Rather than cloud the waters, Dylan’s “Plutarch. Was that his name?” (probably tongue-in-cheek; cf. his delicious concoction of Ovid and Kafka in Chronicles) settles the case: Petrarch it is. The best, and close to only, candidate for “a book of poems… written by an Italian poet from the thirteenth century” (i.e. the 13 hundreds…) in the context of this song (TUIB) is the Laura sonnets; should Dante be a candidate, the relevant work would be Vita Nuova (and definitely not the Comedy), which is much less likely (try to read it!). Boccaccio is out of the question.

Concerning Charon’s “‘eyes like burning coal’, as Wordsworth translates,” and which “seems to echo in “Tangled Up In Blue””: The translation quoted is John Herman Merivale’s from 1838 (did Wordsworth ever translate Dante? I don’t think so); this translation is both incomplete (Merivale only translated selected extracts) and quite unreadable; Dylan has read Inferno, of course, but it is wildly implausible that he has read Merivale’s translation. To make it brief (including the ‘wheels of fire’-reference), this is nonsense as far as the specifics go.

However, the major point of the piece, that Dante’s famous image of the autumn leaves in Canto 3 (which he borrows, or steals, from book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid, who in his turn is inspired by Homer) can be made relevant for a reading of Dylan’s “Walkin’ through the leaves, falling from the trees” is enriching! Just keep TUIB out of it; Dylan is a reader, and consequently knows his Dante; we don’t need BOTT-dylanology to prove that…

Thanks Amund.

To clear up a small misunderstanding, I was referring, ambiguously apparently, to Cary’s translation as published by Wordsworth Classics Of World Literature. Carlyle, in 1859, also translated it as “Charon the demon, with his eyes of burning coal”.

However, I do not think we should take Dylan’s statements, either in lyrics or in interviews or in Chronicles, too seriously. Admirers have a strong tendency to catalogue Dylan’s mistakes and malapropisms under “tongue-in-cheek”, “irony” or “jokingly”, but after sixty years of malapropisms and making mistakes, we should maybe also take into consideration: perhaps academic correctness in literature is not entirely Dylan’s forte.

I therefore seriously doubt that “Dylan knows his Dante”. Dylan himself undermines the relevance of that mythical “book of poems” by omitting it in live versions or by changing it into “Bible”, “Jeremiah” or “Baudelaire” … apparently “Italian poet” is rather interchangeable.

In general, I see little convincing evidence that Dylan is a sharp literary analyst. Which does not in any way detract from the beauty of his lyrics, obviously. But he seems to me to be more of an admiring browser and cherry-picker. From La Vita Nuova he seems to have learned the rather special sonnet form for “No Time To Think”, for example. This reversal of the classical Petrarchan sonnet can hardly be found anywhere in world literature… only in two poems from La Vita Nuova (Ch. VII and Ch. VIII) and in “No Time To Think”.

Anyway, I am getting carried away here. Just wanted to clear up “Wordsworth”, actually. Thank you for your serious, thorough comment and your kind words.

Been away for a while, but thank you, yourself! Yes, it struck me a minute after I posted my comment, ‘oh, he probably means Wordsworth Classics’… I am still a bit confused as to which translations are cited, though; the first quotation seems to be Merivale (“the dæmon,” etc., where Cary has “Charon, demoniac form, / With eyes of burning coal, collects them all,/ Beckoning, and each, that lingers, with his oar / Strikes”), whereas the second quotation (“As in the autumn-time the leaves fall off,” etc.) actually seems to be from Henry Longfellow’s translation? Never mind, this is not a Dante forum (I could wish, however, than more posts on Untold named the translations used when speculating about “intertextual connections” with Dylan’s work…). – I agree that “knows his Dante” is a trifle too highbrow in a description of Dylan; after all, he does confuse the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries in TUIB – … unless he had Guido Cavalcanti on his mind when he wrote that line… but I endorse your remark that there is “ground to the theory that the bard has no particular poet in mind at all, but in this verse line, as is often the case, chooses the *sound*”. My point was just that if you have to choose between Petrarch, Dante, and Boccaccio, Petrarch is the man (“Plutarch? Was that his name?”).

I also agree that we should not “take Dylan’s statements, either in lyrics or in interviews or in Chronicles, too seriously.” But to describe Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a “scary horror tale” must be a deliberate joke informed by Kafka’s Metamorphosis-story about Gregor Samsa. It does not make sense any other way, at least not to me.

Keep up the good work – comments on Dylan’s poetry on this site are always enlightening whether one agrees on every point or not.

PS. And I am looking forward to checking out the Vita Nuova-connection with No Time To Think! Highly interesting; first thing is to look around here on Untold to see if the story has been told more fully already… There’s hot stuff here and it’s everywhere I go.

Takk, Amund. The article in question indeed has been published here (https://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/10725), but I’m afraid it’ll disappoint you; though the article is quite extensive, the Vita Nuova-connection is only superficially noted (noting just the rather similar reversal of the Petrarchan sonnet).

Groeten uit Utrecht!