The Mississippi-series, part 11

by Jochen Markhorst

Like earlier “Desolation Row” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, “Mississippi” can’t really be dealt with in one article. Too grand, too majestic, too monumental. And, of course, such an extraordinary masterpiece deserves more than one paltry article. As the master says (not about “Mississippi”, but about bluegrass, in the New York Times interview of June 2020): Its’s mysterious and deep rooted and you almost have to be born playing it. […] It’s harmonic and meditative, but it’s out for blood.

XI Bonnie Blue

Well I got here followin’ the southern star

I crossed that river just to be where you are

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

One of the few successful songs on one of Dylan’s weakest albums, Down In The Groove (1988) is his version of the old folk song “Shenandoah”. It is, of course, a beautiful nineteenth century song by itself – almost impossible to ruin.

One of the few successful songs on one of Dylan’s weakest albums, Down In The Groove (1988) is his version of the old folk song “Shenandoah”. It is, of course, a beautiful nineteenth century song by itself – almost impossible to ruin.

The origin of “Shenandoah” is unclear. Alan Lomax guesses it’s a sea-shanty, an old sailor’s song of French-Canadian origin, probably originated around 1810. Given the lyrics, other musicologists conclude, it might be a “river-shanty”, deriving its name from the Shenandoah River in Virginia. Why then the protagonist repeatedly sings he has to cross the Missouri River is unexplained, though – that particular river is almost a thousand miles away. “Shenandoah” is a singing, melodious name, that’s probably the best explanation.

Oh Shenandoah, I love your daughter Look away, you rollin' river It was for her I'd cross the water. Look away, we're bound away Across the wide Missouri

Dylan sings the version in which the narrator so desperately seeks to reach “Sally”, across the wide Missouri, and she is the “daughter of Shenandoah”. Which could indicate an Indian tribe, or the name of the river where she lives, or, in the literal interpretation, the name of his future father-in-law. “Oh Shenandoah, I love your daughter,” after all.

The Indian tribe-option is by far the most attractive to lay a line to “Mississippi”. The Senedos, a tribe along the Shenandoah River, are the obvious candidates – all the more so since Shenandoah in their language means “daughter of the stars”. Following the star, I crossed the river. Coincidence, of course, but certainly a nice coincidence.

The real link, however, is that ancient image of “crossing a river”, the metaphor to represent the effort the man makes to reach the woman of his dreams. We sang that already in the Middle Ages:

Het waren twee koninghs kindren, Sy hadden malkander soo lief; Sy konden by malkander niet komen, Het water was veel te diep. There were two royal children, Their love was turned to grief. They could not come together The water was too deep.

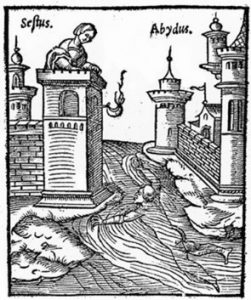

The “Song of the Two Royal Children”, about the regal kids who are not allowed to see each other. One king puts his daughter in the monastery, on the banks of the wide river. She puts a candle on the balustrade at night so that the king’s son on the other bank can orient himself as he swims towards her, in pitch darkness. An “evil nun” blows out the candle when he is halfway, the king’s son drowns, and when his beloved finds the body the next morning, she commits suicide out of desperation.

A familiar story which, of course, goes back to the age-old Greek myth Hero and Leander, the story that inspired hundreds of artists from Antiquity to the twenty-first century – it’s an ancient, popular and ineradicable image, the river separating lovers. Or as a metaphor for every figurative meaning of “border” at all; it is not a coincidence that watershed is synonymous with milestone, radical event, turning point. Which is how the poet Dylan uses river throughout his entire oeuvre. From “Watching The River Flow” to “Baby, Stop Crying” and from “Man In The Long Black Coat” to “Moonlight” and “Crossing The Rubicon”; the rivers symbolize turning points.

In “Mississippi” Dylan gives it an extra, mythical touch; the narrator follows the southern star that leads him to that turning point. Mythical, as a Southern star does not exist – unlike a North Star, Polaris, there is no fixed star in the southern sky. A less romantically inclined astronomer might argue that the Sun is “the star in the south”, but in the arts it’s usually a nickname (for a special diamond, for example, as in the film The Southern Star with Orson Welles and an Ursula Andress at her most beautiful, 1969). It’s not really a household name, though.

Presumably the poet wants to avoid digressing – after all, the star in any other wind direction has additional meanings or associative consequences. The Star in the East leads to the Child Jesus, the aforementioned North Star, which is shining too in one of Joni Mitchell’s breath-taking songs, “This Flight Tonight”,

"Look out the left," the captain said "The lights down there, that's where we'll land" Saw a falling star burning High above the Las Vegas sand It wasn't the one that you gave to me That night down south between the trailers Not the early one that you wish upon Not the northern one that guides in the sailors

…is an age-old orientation point. And a Western Star conjures up completely different images, obviously. So, all that’s left is a “safe”, a neutral southern star. At most it pushes the associations, especially in the light of Dylan’s enigmatic statement that the song is about “the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights”, towards the Civil War, to the Bonnie Blue Flag hoisted on the Capitol Dome of Mississippi in 1861.

That flag consists of a single, large, “Southern” star on a blue field. In the South it is popular, a hastily written song perpetuates its popularity and promotes the flag to become the first unofficial flag of the Confederate States of America:

We are a band of brothers, and native to the soil, Fighting for our liberty with treasure, blood, and toil; And when our rights were threatened, the cry rose near and far, Hurrah! for the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a single star.

The song is sung in Gods And Generals (2003), the film for which Dylan writes the brilliant “Cross The Green Mountain” (well after “Mississippi”) and the cinephile Dylan will have noticed the song earlier in Gone With The Wind – Rhett Butler lovingly calls his daughter Bonnie “Bonnie Blue”, Melanie (Olivia de Havilland) says her eyes are “blue as the Bonnie Blue Flag”.

Too bad the movie’s in Georgia. And not in Mississippi.

The Bonnie Blue Flag – Gods and Generals

To be continued. Next up: Mississippi part XII: Roses Of Yesterday

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

You sure that’s a correction interpretation of the song “Shenandoah”.

I take it that the guy leaves Sally, the daughter of the Shenandoah, whom he loves dearly , and after an unsuccessful seven-year courtship, he heads out West to Missouri country, but there he still yearns for his love back in Virginia.

That is, the original Missouri focus of the song has been turned around.

The theme of Dylan’s ‘Red River Shore’ is somewhat similar to that of the original interpretation of ‘Shenandoah’ – both have a Canadian connection.