by Jochen Markhorst

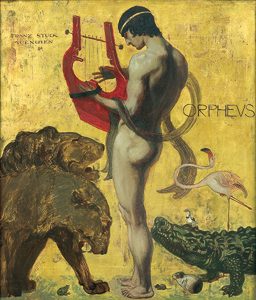

Mysterious musicians with hypnotic skills have been around since Orpheus, who is still the greatest of all; his divine arts on the lyra can already calm storm waves and ward off ferocious warriors, but his singing makes trees bend, the wild animals gather peacefully around him, the rocky rock weeps with emotion – and even the god of the underworld melts.

The musician with magic powers remains a popular protagonist in the following centuries. Further north, from the thirteenth century onwards, the Pied Piper of Hamelin becomes an iconic figure, enriched with demonic traits. After the city council does not pay him for the neatly executed pest control, he retaliates horribly: on St John and Paul’s Day, 26 June 1284, while the adults are in church, he returns, lures all 130 children with his flute and disappears with them auf Nimmerwiedersehen into a mountain. In later centuries, a Disney variant pollutes the original story with a happy ending in which the children return home safely and well, but der Rattenfänger, the Pied Piper, remains a dubious, devilish stranger – dressed in a red suit in most variants.

The more sentimental counterpart emerges in literature and music from the eighteenth century onwards: Il Trovatore, the Good-for-nothing, the Poor Minstrel, the wandering, ragged old man who with his violin, hurdy-gurdy or flute, touching hearts, making crippled children dance and fraternizing enemies. Or symbolising Death, as in the most famous example, the Leiermann from the last song of Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise (1827).

The Tambourine Man fits seamlessly into the row from Orpheus to Leiermann and the charm is easily felt. At the beginning of ’64, when Dylan writes the song, he himself is a Pied Piper who shows the way with his music, brings masses on their feet and enchants followers. With this song again: the extraordinary beauty of “Mr. Tambourine Man” gives birth to folk rock and devout disciples: The Byrds will record over twenty more songs by Dylan in the years following the world’s success with this song, thus contributing to the spread of His word.

En passant Dylan reintroduces the musical magician in popular culture; Chrispian St. Peters scores a world hit in 1966 with “The Pied Piper” (a cover – the original is from the band The Changin’ Times, what’s in a name), the men from Status Quo are still called The Spectres when they score their first hit with “Hurdy Gurdy Man”, Dylan disciple Donovan has a hit with another organ grinder, who is also called “The Hurdy Gurdy Man”, with  considerably more success (’68), director Jacques Demy then asks the same Donovan for the leading part in his film The Pied Piper, 1972, and Led Zeppelin lends for “Stairway To Heaven” not only the smoke rings but also the image of the piper who takes you with him.

considerably more success (’68), director Jacques Demy then asks the same Donovan for the leading part in his film The Pied Piper, 1972, and Led Zeppelin lends for “Stairway To Heaven” not only the smoke rings but also the image of the piper who takes you with him.

The king of the Philistines, who in Dylan’s “Tombstone Blues” (1965) locks up all those whistling scum (“Puts the pied pipers in prison”) hasn’t been able to turn the tide.

The song is an exceptional masterpiece even by Dylan standards and is, with crown jewels such as “Blowin’ In The Wind”, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” and “The Times They Are-A Changin'”, now part of the World Cultural Heritage.

At the time of conception (spring ’64) the maestro also seems to have realised that he has something special in his hands. Contrary to his custom, he cannot make up his mind for a definitive recording, so that it does not end up on Another Side Of.

That first recording, with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, indeed does not have the je-ne-sais-quoi that should elevate the song to a classic, and a remarkably critical Dylan rightly dismisses it. In the studio as well as on stage he fortunately stays true to it, in the months that follow. He is proud of “Mr. Tambourine Man”, often plays it to colleagues and friends and the song immediately stands firm on his repertoire. It even seems to be the only song of which he ever tried to make a “sequel”; “I tried to write another “Mr. Tambourine Man”. It’s the only song I tried to write ‘another one’”.

That’s debatable by the way (there are some “Like A Rolling Stone Part Two’s”, for instance), but it does indicate that Dylan himself recognizes the extravagant class of the song.

Fortunately, the long twisting and turning around does not lead to him polishing the song to death, as will happen later on with other brilliant songs (with “Caribbean Wind”, for example). The final version, the sixth take recorded at the Bringing It All Home sessions, is sober. Second guitarist Bruce Langhorne (Mr. Tambourine himself, by the way, because of the extremely large tambourine he carries around for a while) occasionally misses some notes and Dylan also plays far from flawless – perfect imperfection all in all.

Dylan’s paternal pride would have been twofold. On the one hand there’s the melody, which came all from himself. Dylan did not “appropriate”, like with so many of the songs before, he hasn’t siphoned off anything from antique folk songs. But even bigger are the lyrics.

“Rimbaud is the man,” says Dylan in those days, that’s the way he wants to write. And it shows. The perspective of Dylan’s poetry shifts radically: from the outside to the inside: “Hey Woody Guthrie, I wrote a song for you” has become “Hey Mr. Tambourine Man, play a song for me”. He doesn’t want to know anything more about the so-called finger-pointing songs anyway, as we can see on Another Side Of. But most of the songs on that record are still pointing outwards, speaking to something or someone. Only “Spanish Harlem Incident” has shreds of impressionistic portrait painting, and is a steppingstone to the poetic explosion that “Mr. Tambourine Man” is.

Stylistically, the text is just as swirlin’ as its content. The poet weaves myriads of rhyme words (sand-hand stand, feet-meet-street) assonances (windy beach-twisted reach) and alliterations (culminating in silhouetted by the sea, circled by the circus sands) and perfectly feels when he has to break the cadence of the rhyme scheme – nowhere does the lyric twaddle or drone.

In terms of content, the influence of Rimbaud is undeniable. The visionary, dreamy symbolism in decor descriptions such as the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming and to dance beneath the diamond sky seem to come straight from the oeuvre of the French magician. Rimbaud sings of the feux à la pluie du vent de diamants in his Illuminations, just as the image the magic swirlin’ ship will be borrowed from Rimbaud’s famous “Le bateau ivre”. But even more than these traceable images and sets, Dylan adopts the shift in perspective towards an elated, dizzy protagonist, the misty I figure who captures his grand feelings in impressionistic, frayed sensory impressions. Especially according to Rimbaud’s dictum from the Lettre du Voyant: “The poet becomes a seer through a profound, deliberate disruption of all his senses.

Idiomatically, Dylan does borrow some scraps too, left and right. The jingle jangle, for instance, he heard from Lord Buckley (from Scrooge; “jingle jangle bells all over”), whose LP The Best Of is not entirely coincidental on the carefully composed cover of Bringing It All Back Home (on the mantelpiece). Lord Buckley’s oeuvre, incidentally, also contains a version of the inspiring Pied Piper story: “The Swingin’ Pied Piper” (1959).

Idiomatically, Dylan does borrow some scraps too, left and right. The jingle jangle, for instance, he heard from Lord Buckley (from Scrooge; “jingle jangle bells all over”), whose LP The Best Of is not entirely coincidental on the carefully composed cover of Bringing It All Back Home (on the mantelpiece). Lord Buckley’s oeuvre, incidentally, also contains a version of the inspiring Pied Piper story: “The Swingin’ Pied Piper” (1959).

Unlike most poetry masterpieces, in which the opening line, or one citable verse, or perhaps one verse, transcends the work and becomes more famous than the poem itself, “Mr. Tambourine Man” is a Gesamtkunstwerk, a poem that shines from head to toe, from the first to the last line. At the most, the closing line of that magnificent final section removes itself a bit from the song, “Let me forget about today until tomorrow”. But there Dylan paraphrases one of the most beautiful lines from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Take therefore no thought for the morrow: for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof” (Matthew 6:34).

Hundreds of covers, of course. In every language, colour and genre imaginable. Right from the start, too: in the year of birth 1965 alone, fourteen cover versions are recorded. Some, like the one by The Byrds, are even released before Dylan’s own version. The first one, before The Byrds, is by the folk quartet The Brothers Four and is quite nice. Among the more hilarious lows is Captain Kirk’s cover, William Shatner (his version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” is perhaps even worse).

Fans can be found in every corner of the music universe, so it often goes wrong, but in the vast majority of interpretations the song retains its power, or at least its charm. In 2008, one Jason Castro makes it to the American Idols final with a faithful, beautiful rendition, usual suspects like Judy Collins, Odetta and Melanie are equally safe and nice. The Beau Brummels deliver a pleasant, slowly derailing version – unfortunately though, they succumb to the temptation of a neurotic tambourine from start to finish. The best of the rest is ex-Byrd Gene Clark on his ironically titled collector Flying High (his crushing fear of flying was one of the reasons he left The Byrds).

Actually, only two covers can compete with Dylan’s inviolable monument. The first comes from the Icelandic Premier League, from the enchanting Ólöf Arnalds, performing live at KEX Hostel with her sister Klara. Just a charango, the lute-like string instrument from the Andes, played by Ólöf. But most of all: the magical, swirling, amazing singing by the sisters – yes, you hear vague traces of skippin’ reels of rhyme and fate, driven deep beneath the waves (first goose-bumps at 1’17’’).

Ólöf Arnalds:

The other one is quite modern, and has the bonus of being from Dylan’s birthplace: in 2006, the local heroes of Cloud Cult, a very cute indie rock band, contribute a hypnotic, experimental, magic swirlin’, driving “Mr. Tambourine Man” to the sympathetic tribute project Duluth Does Dylan Revisited. Their live version on Live at KEXP Vol. 3 is very successful too, as is the alternative take that ends up on Lost Songs From The Lost Years (2011).

Brooding, hypnotizing and magical – as an Orpheus in top form.

Cloud Cult:

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/428/Mr-Tambourine-Man

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.