by Jochen Markhorst

- Bob Dylan’s Blues (1962): part I – A Greatest Hit???

- Bob Dylan’s Blues (1962): part II – Come back to the five and dime, Jimmy Reed

On August 6, 1986, Dylan plays a rather acclaimed concert in Paso Robles, California, accompanied by Tom Petty. Nice setlist, with a beautiful tribute to Ricky Nelson (“Lonesome Town”), who was killed in a plane crash on New Year’s Eve; with the live debut of “Brownsville Girl” (partly at least – Dylan only plays the chorus); with some nice covers (“Uranium Rock”, for example, and “Across The Borderline”) and with an attractive mix of old and new own work. Dylan is in a good mood, praises the quality of The Heartbreakers, his band (“It’s a real rock ‘n’ roll band here”) and is pleased that old comrade Al Kooper joins in for “Like A Rolling Stone”.

On August 6, 1986, Dylan plays a rather acclaimed concert in Paso Robles, California, accompanied by Tom Petty. Nice setlist, with a beautiful tribute to Ricky Nelson (“Lonesome Town”), who was killed in a plane crash on New Year’s Eve; with the live debut of “Brownsville Girl” (partly at least – Dylan only plays the chorus); with some nice covers (“Uranium Rock”, for example, and “Across The Borderline”) and with an attractive mix of old and new own work. Dylan is in a good mood, praises the quality of The Heartbreakers, his band (“It’s a real rock ‘n’ roll band here”) and is pleased that old comrade Al Kooper joins in for “Like A Rolling Stone”.

But he doesn’t talk about any of that, a little later in the interview with the co-writer of “Brownsville Girl”, with Sam Shepard:

BOB: Oh, you know where I just was?

SAM: Where?

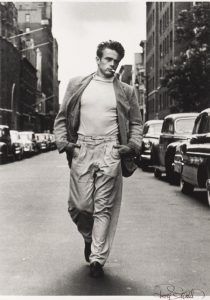

BOB: Paso Robles. You know, on that highway where James Dean got killed?

SAM: Oh yeah?

BOB: I was there at the spot. On the spot. A windy kinda place.

SAM: They’ve got a statue or monument to him in that town, don’t they?

BOB: Yeah, but I was on the curve where he had the accident. Outsida town. And this place is incredible. I mean the place where he died is as powerful as the place he lived.

James Dean is an indestructible hero to Dylan. He brings him up regularly, unsolicited too, always admiring him. It must have flattered him that journalists and biographers often compare him to James Dean – a comparison that is officially recorded by Don McLean in the immortal pop monument “American Pie” (1971), in which Bob Dylan plays a small part, as “the jester”:

When the jester sang for the king and queen In a coat he borrowed from James Dean

When asked, in the Bill Flanagan interview 2017, Dylan is not too happy with that comparison with a joker (“A jester? Sure, the jester writes songs like ‘Masters of War’, ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’, ‘It’s Alright, Ma’ – some jester. I have to think he’s talking about somebody else. Ask him”), but Don McLean is not entirely wrong.

In that conversation with Sam Shepard – one of the best Dylan interviews ever – Dylan is quite explicit about the life-decisive influence of the young deceased actor:

BOB: Naw. The only reason I wanted to go to New York is ’cause James Dean had been there.

SAM: So you really liked James Dean?

BOB: Oh, yeah. Always did.

SAM: How come?

BOB: Same reason you like anybody, I guess. You see somethin’ of yourself in them.

Dean was a racing fanatic, took part in racing races, and, as we know, he died in his Porsche 550 on his way to yet another race in Salinas. And echoes of that crash the jester in a coat borrowed from James Dean seems to process in the third verse of “Bob Dylan’s Blues”:

Lord, I ain’t goin’ down to no race track See no sports car run I don’t have no sports car And I don’t even care to have one I can walk anytime around the block

The gimmick of the first two verses, contrasting anomaly and cliché, is gone. The third verse has no “inner conflict”. Although a “sports car” is a unusual attribute in a song in 1962 (in January ’63, shortly after the creation of this song, Elvis sings “(There’s) No Room To Rhumba In A Sports Car” – there are hardly any other examples), a sports car is, unlike the Lone Ranger and unlike the five and ten cent women, not alienating or unrealistic; the couplet has – again – no relation to the other verses, but is in itself a weekday, realistic tableau.

With some tolerance there seems to be, for the first time, a kind of storyline to the following verse. The narrator has just told us that he could walk around the block, and now the narrator indeed is walking in the street:

Well, the wind keeps a-blowin’ me Up and down the street With my hat in my hand And my boots on my feet Watch out so you don’t step on me

…but it’s not really gonna be a story. It’s another stand-alone tableau, this time with a high Woody Guthrie content. Spoken, it seems, by Dylan’s protagonist from “I Was Young When I Left Home”, or rather from “Man On The Street”, that old hobo who dies so lost and lonely on the street. A Guthrie archetype anyway, but Dylan also borrows his vernacular – from “Goin’ Down The Road”, for example:

I'm blowin' down this old dusty road I'm a-blowin' down this old dusty road I'm a-blowin' down this old dusty road, Lord, Lord An' I ain't a-gonna be treated this a-way

But then again, the choice of words and images are clichéd enough to have been raked out of dozens of other songs. In these same days, Jimmy Dean (what’s in a name) writes a sequel of his hit “Big Bad John”, called “Little Bitty Big John”, containing the words his hat in his hand, to name just one other possible lyric influencer.

Anyway, this tableau, this fourth verse, has nothing more to offer than a snapshot, is nothing more than a stand-alone intermezzo.

A similar loose link as from the third to the fourth verse seems discernible, again with some leniency, from the fourth to the last verse. The Great Common Divider is then Woody Guthrie, and again the vernacular, the specific jargon, is a first trigger. In this case the somewhat dated lookit. Though Dylan uses it differently, here. Guthrie uses it as a phonetic short-cut for look at. As in his autobiography Bound For Glory (“I got ’em! I got ’em! Hi! Lookit me!”) and as in a song like “Dry Bed” (“Hey, lookit my dry bed! Come feel my dry bed!”) – where, by the way, both in his book and in the songs, “lookit” most of the time is said by children.

In the 1940s, the somewhat shabby, hillbilly-ish word shifts to Hollywood, to the city, and even to the elite. In a recorded phone conversation between President Kennedy and the Mayor of Chicago, Richard Daley, we hear how Daley teaches party discipline to a colleague: “He’ll do it. The last time I told him, ‘Now lookit… you vote for anything the President wants‘… and that’s the way it’s gonna be.”

In migrating to a higher social class the meaning has shifted too, apparently. Now it means something like “listen”, “look” – and that’s how Dylan applies it here:

Well, lookit here buddy You want to be like me Pull out your six-shooter And rob every bank you can see Tell the judge I said it was all right Yes!

No, that’s not how Woody uses it. It’s a lookit, actually, like it’s exclusively sung by Howlin’ Wolf. Like in “Mr. Highway Man” from 1952 (“Lookit here, man, please check this oil”), but especially like in the Mother of all Blueses, in the template for all slow blues songs, in “Goin’ Down Slow”:

Now lookit here I did not say I was a millionaire But I said I have spent more money than a millionaire

Not too far-fetched, of course. Dylan’s love for Howlin’ Wolf is well documented, this version of “Goin’ Down Slow” has just been released on single, the song gets a name-check in Dylan’s “Caribbean Wind” (1980) and again, more explicitly, in 2020 on Rough And Rowdy Ways. Twice even, both in “Key West” and in “Murder Most Foul”.

After that intentional or accidental detour Dylan ends up with Woody Guthrie again, with one of his signature songs, “Pretty Boy Floyd”. According to the narrator, the addressed buddy has to live his life just like the I-person does, just like the romanticized version of that bank robber: with his six-shooter he is allowed to rob banks. Because banks, as the myth around Pretty Boy Floyd says, are the heartless, greedy institutions that evict poor, honest and hardworking people from their homes. “And tell the judge I was okay with it.”

Words of a rebel with a cause.

“Bob Dylan’s Blues” is still not a Greatest Hit. On stage Dylan will never perform it, the song is ignored by colleagues and it is never selected for compilation albums. Except that one time, for the very first Bob Dylan Greatest Hits album. Actually, it’s a bit puzzling that it was even selected at all for The Freewheelin’, instead of small masterpieces like “Tomorrow Is A Long Time” and “He Was A Friend Of Mine”, or more successful songs like “Let Me Die In My Footsteps” and “Quit Your Low Down Ways”. Or one of the many other songs Dylan records in these same days, which are not officially released until decades later.

Still, we have to hand it to the anonymous compiler of that stern musik compilation: “Bob Dylan’s Blues” is a rudimentary sample of the things to come. The surreal touch of the opening stanza with The Lone Ranger predicts the disruptive, poetic explosions like “Farewell Angelina” and “Tombstone Blues”. The love poetry of the second strophe announces “Love Minus Zero”, the urban blues of the third verse promises a return to Highway 61 and the last two strophes illustrate the folky Woody Guthrie phase in which the young Dylan currently still is wallowing.

Thus, the 2’28” of “Bob Dylan’s Blues” is like the overture of a Mozart opera: in two and a half minutes, the ditty divulges the highlights of the next four years, the years up to 29 July 1966, the day Dylan barely escapes a James Dean final.

=======

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/84/Bob-Dylans-Blues

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.