by Jochen Markhorst

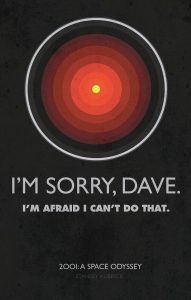

It is a missed opportunity for IBM. They should of course have called their talking supercomputer HAL, the name of the talking computer from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odessey (1968). Writer Arthur C. Clarke later stated, quite convincingly, that it was just a sheer coincidence, but to no avail: the fact that an alphabetical one-letter shift changes “HAL” into “IBM” (H becomes I, A becomes B, and M becomes L) is too good to be coincidental. Film fanatics and Dylanologists don’t differ that much – some of them really do have a tendency, or perhaps an urge, to see more than there actually is.

It is a missed opportunity for IBM. They should of course have called their talking supercomputer HAL, the name of the talking computer from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odessey (1968). Writer Arthur C. Clarke later stated, quite convincingly, that it was just a sheer coincidence, but to no avail: the fact that an alphabetical one-letter shift changes “HAL” into “IBM” (H becomes I, A becomes B, and M becomes L) is too good to be coincidental. Film fanatics and Dylanologists don’t differ that much – some of them really do have a tendency, or perhaps an urge, to see more than there actually is.

IBM, however, misses the opportunity for free publicity and brand awareness. Perhaps also because HAL is not that nice; after all, he kills almost the entire crew of Discovery One, including, in a cowardly manner, the three travelling scientists who spend the journey time frozen, in “cryonic sleep”, in their survival capsules.

It will eventually become “Watson”, which may be a second mistake. It is meant as an honourable naming after Thomas J. Watson the founder of IBM, but of course the whole world only thinks of Sherlock Holmes, of his sounding board John H. Watson. Not necessarily the association you want to evoke if you want to sell a supercomputer, since Watson is the permanently amazed, never understanding, in all respects average side-kick of the superior, human supercomputer Holmes.

Anyway, the commercial is funny. In 2015 the IBM marketing department manages to attract Bob Dylan for an amusing advertising film, in which Watson converses with the bard. Watson claims to have analysed all of Dylan’s songs.

“Your main themes are,” Watson concludes, “Time Passes and Love Fades.”

“That sounds about right,” Dylan answers amused.

Watson’s claim really is about right. IBM spokeswoman Laurie Freedman officially reports that the researchers have actually fed 320 of Dylan’s songs into Watson and his analysis has in fact distilled the themes mentioned. Watson’s ability to “personality analysis, tone analysis and keyword recognition” has helped to better understand the data. All right, not “all of Dylan’s songs” (Dylan has written more than six hundred songs), but still more than half of them.

It doesn’t cost Watson any effort of course (by his own account he reads 800 million pages per second), but he could have saved himself some trouble: Watson would already have been there if he had confined himself to “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”.

Dylan writes “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” in 1962, records it in the autumn and 27 May 1963 it appears on the legendary LP The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. To put it mildly, the song is indebted to “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone)” from Dylan’s friend Paul Clayton, who in turn based it on a nineteenth-century “Negro song”, on “Who’s Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I’m Gone”, as well as quoting from the traditional “Scarlet Ribbons for Her Hair”.

Not only the melody, but also considerable fragments of text from Clayton’s 1959 song Dylan copies almost unchanged: It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, darlin’ and So I’m walkin’ down that long, lonesome road and You’re the one that made me travel on, for example.

Which is not considered plagiarism in those days – it is customary to polish up or cut up each other’s songs, or old folk and blues songs. However, it is not very honourable to claim copyright, which is what Dylan does. By the way, he effortlessly acknowledges his indebtedness:

“Paul was just an incredible songwriter and singer. He must have known a thousand songs. I learned Pay Day At Coal Creek and a bunch of other songs from him. We played on the same circuit and I traveled with him part of the time. When you’re listening to songs night after night, some of them rub off on you. Don’t Think Twice was a riff that Paul had. And so was Percy’s Song.”

(liner notes Biograph, 1985)

Twenty years earlier, in an interview with Helen McNamara for Toronto Telegram (3 February 1964, published in Gargoyle too), Dylan is similarly enthusiastic about Clayton, and confesses a mystical awe for his qualities as a folk musician:

“The only guy I know that can really do it is a guy I know named Paul Clayton, he’s the only guy I’ve ever heard or seen who can sing songs like this, because he’s a medium, he’s not trying to personalize it, he’s bringing it to you … Paul, he’s a trance.”

The admiration is mutual, and the openly homosexual Clayton may also be a bit charmed by the young Dylan, so it does not disrupt the friendship. Outside the courtroom, lawyers from the respective music publishers settle on a buy-off of any claims. Clayton receives a modest amount of money, and does not complain.

To Clayton, it hardly could be a sensitive issue, for that matter. He may be “an incredible songwriter”, but he is above all, just like Dylan, a thief of thoughts, a miner who digs up old melodies, ennobles them and records them (Clayton has released about twenty records). He does this digging at home in West Virginia, in the university library of Charlottesville. That’s where he found the template for his “Who’s Gonna Buy You Ribbons (When I’m Gone)”; in an obscure booklet from 1923, the collection Eight Negro Songs. Editor Alfred J. Swan admires in the foreword the musicality and originality of those nineteenth century songs,

“the rich imagery, the racy humour, the naive pathos, and the simple, yet original philosophy of the modern negro’s mind,”

and also gives a crash course negro dialect, for he has transcribed the songs as faithfully as possible:

Who gon bring you chickens when I’m gawn? Aw! Ba-beh! Who gon bring you chickens when I’m gawn? Six mont’s in jail ain so long, Aw, dahlin Hit’s wukkin on dat county farm.

Clayton turns those chickens into ribbons, and concocts some sentences around them. By the looks of it, he has browsed a few more pages; on page 36 “Dat Lonesome Road” is printed:

True love, true love, what hev I done To mek you treat me so You’ve made me walk dat lonesome road, Like uh nuvvuh done befo’ Look down, look down dat lonesome road, Hang down my head an’ cry

According to commentators, Clayton takes a few melodic things from another old West Virginia folk song, from “Call Me Old Black Dog”. An antique recording of that song by Dick Justice, 1929, does not illustrate this claim, though:

Anyway, Clayton is actually doing the same thing as Dylan is doing with Clayton’s Ribbons song – which is why indignation would be somewhat misplaced. Entirely in line, by the way, with the somewhat cynical quote attributed to Clayton:

“If you can’t perform, write; if you can’t write, rewrite; if you can’t rewrite, copyright; if you can’t copyright, sue.”

Paul Clayton dies 30 March 1967 in his New York apartment. He sits down in the bathtub and electrocutes himself by dropping his electric heater into the water. It is less than two years after Dylan’s electric attack on acoustic folk, after “Maggie’s Farm” at the Newport Folk Festival. Far-fetched perhaps, or even a bit disrespectful, but it almost seems as if the intelligent and sensitive Clayton, the standard-bearer of acoustic traditional folk music, has staged his suicide as a metaphor.

It ain’t no use in turnin’ on your light, babe, I’m on the dark side of the road.

To be continued. Next up: Don’t Think Twice – part II: Love Fades

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down