by Jochen Markhorst

She belongs to me

- She Belongs To Me (1965): I – No colours anymore

- She Belongs To Me (1965) part II: Images which have got to come out

- She Belongs To Me (1965) part III: Walking in darkness

IV Marie is only six years old

The brilliant closing stanza, finally, reaffirms the ironic overtones – though on a different level. As with, for example, the beautiful Basement song “Nothing Was Delivered”, or in “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, or “Highway 61 Revisited” (there are many examples), we see in this verse Dylan’s artistic kinship with that other great Jewish poet, with Heinrich Heine, the patriarch of the Ironische Pointe, the ironic punch line. With this stylistic tool, the writer destroys expectations by ending lofty, sentimental or melancholy lines with an inappropriate platitude, a dry comic footnote or a vulgarity. Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters is one of Dylan’s best-known, but this one ain’t bad either:

The brilliant closing stanza, finally, reaffirms the ironic overtones – though on a different level. As with, for example, the beautiful Basement song “Nothing Was Delivered”, or in “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, or “Highway 61 Revisited” (there are many examples), we see in this verse Dylan’s artistic kinship with that other great Jewish poet, with Heinrich Heine, the patriarch of the Ironische Pointe, the ironic punch line. With this stylistic tool, the writer destroys expectations by ending lofty, sentimental or melancholy lines with an inappropriate platitude, a dry comic footnote or a vulgarity. Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters is one of Dylan’s best-known, but this one ain’t bad either:

Bow down to her on Sunday Salute her when her birthday comes For Halloween give her a trumpet And for Christmas, buy her a drum

The first two verses still are a logical result of all the previous character descriptions. This is a very special lady, far above us, simple footmen, a lady who may only be admired kneeling and from a distance. The poet emphasizes her majesty with appropriate, status confirming imperatives: bow down and salute her, to finally contrast all the more inappropriately with the sobering punch line. The glorified dame receives a trumpet and a drum.

A trumpet and a drum? For an unassailable highness? Is this really a majestic ladyship being sung here?

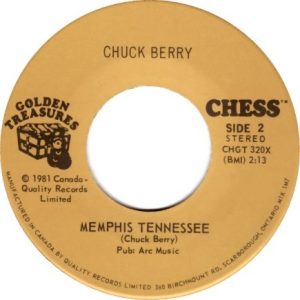

In 1958 Chuck Berry records “Memphis, Tennessee”. The song undeniably belongs to the rock canon, to the elite of indisputable rock monuments – after all, the song is a member of the very exclusive and very small club of songs recorded by the Holy Trinity; by Elvis, The Beatles and The Stones. And large parts of the premier league just below that Olympus also honour the masterpiece with studio recordings and live performances. The Who, Jerry Lee Lewis, Led Zeppelin, Roy Orbison, Bo Diddley, Rod Stewart and, well, anyone who can hold a guitar, basically.

The song is deceptively simple. Two chords. The primal version, Chuck’s recording, is rough and rowdy. Simplistic drumming on a single tom, no bass (the low strings of the electric guitar provide the service), languid, sloppy licks by Chuck on his guitar, and after two minutes and a bit it’s done. Pieced together all by himself, as Berry remembers in his memoirs (Chuck Berry: The Autobiography, 1987):

“Memphis Tennessee” was recorded in my first office building at 4221 West Easton Avenue in St. Louis on a $145 homemade studio in the heat of a muggy July afternoon with a $79 reel to reel Sears & Roebuck recorder that had provisions for sound-on-sound recording. I played the guitar and bass track, and I added the ticky-tick drums that trot along in the background which sound so good to me. I worked over a month revising the lyric before I took the tape up to Leonard Chess to listen to. He was again pressed for a release since my concerts (driving on the road then) kept me from the recording studio for long periods.

On the level of details, Berry’s book is full of minor mistakes (in those years, Sears & Roebuck didn’t have a $79 reel-to-reel tape recorder for sale that would allow sound-on-sound, for example), but the big picture is probably correct. Berry also recognises what makes the song such an exceptional masterpiece: not so much the music, however brilliantly simple it may be, but the lyrics, on which he has been polishing for more than a month after that primal recording.

The unbridled brio, obviously, is in the twist. For three verses we hear a pitiful sucker trying to call his girl in Memphis – but he has lost the number. He begs the operator to help him –

Long distance information, give me Memphis, Tennessee Help me find the party trying to get in touch with me She could not leave her number, but I know who placed the call Because my uncle took the message and he wrote it on the wall

… and desperately bombards the poor telephone operator with useless information about Marie and her whereabouts (“her home is on the south side, high upon a ridge, just a half a mile from the Mississippi Bridge”). So far not very striking; song lyrics in this category, the desperate suitor who cannot reach his girl, we already have come to know in enough variations. Chuck indeed does freely reveal that he copied it from some run-of-the-mill song:

The story of Memphis got its roots from a very old and quiet bluesy selection by Muddy Waters played when I was in my teens that went “Long distance operator give me (something….something), I want to talk to my baby she’s (something else)”. Sorry I don’t remember anymore now but I did then and spirited my rendition of that feeling into my song of Memphis. My wife had relatives there who we were visiting semi-annually but other than a couple of concerts there, I had never had any basis for choosing Memphis for the location of the story.

Again, incorrect at a detailed level, probably. Muddy Waters may have a song called “Long Distance Call” (1951), but that song doesn’t contain the word operator, nor a verse that resembles Chuck’s remembered words. Little Milton’s “Long Distance Operator” looks a bit like it,

Long distance operator Can I talk to my girl tonight? I feel so sad and lonely And you know, I just ain’t feeling right

…but that single was not released until February ’59. Jimmy Reed’s 1957 “Baby What’s On Your Mind” might have been a candidate (“I’d call up the operator and tell her give me your private line / I feel so bad, baby, livin’ downtown all alone”), but that still doesn’t add up to Chuck’s recollection that he heard it in my teens – that should be somewhere in the 1940s.

Not too important, of course. There are dozens of songs in this category. Here too, at least, the spirit of Chuck Berry’s story will be true; that he borrowed the plot’s setting, a man laments his sorrow to an anonymous operator. Just as Dylan and The Band will do for their “Long Distance Operator” (The Basement Tapes), by the way.

More important is the brilliant twist, the punch line that tilts the entire lyrics:

Last time I saw Marie she's waving me goodbye With hurry home drops on her cheek that trickled from her eye Marie is only six years old, information please Try to put me through to her in Memphis Tennessee

This is 1958 – it is perhaps the first pop song to thematise child custody and the resulting suffering of the father after a divorce. And moreover: such an adult theme is enormously out of tune in these years, the years of bubble-gum, surfing fun and high school romance. So, at first, the Chess record company does not quite know what to do with it. It is finally put on a B-side (from “Back in the USA”) in June ’59.

After “Subterranean Homesick Blues”, for which Dylan uses as a template Berry’s “Too Much Monkey Business”, the Father Of Rock and Roll seems to inspire Dylan again, this time on a lyrical level: to the surprising punch line of “She Belongs To Me”, to the conclusion that the sung lady is a girl of about six years old. Who can look forward to a classic Christmas present: a drum.

However, unlike with “Memphis, Tennessee”, the surprising twist does not tilt the whole text. With hindsight, parts of the lyrics take on a different meaning, though. She don’t look back of course suits a six-year-old (who, after all, has no past), nobody’s child suddenly suggests a custody battle and next to a child you are a walking antique, evidently. But fragments like peeking through her keyhole suddenly get a – no doubt unintentional – creepy charge, so: no.

No, “She Belongs To Me” is and remains a beautiful collage song, a mosaic which sketches what goes around her sometimes. With a sparkling twist demonstrating a poetic congeniality with both one of the greatest European poets from the early nineteenth century and the twentieth-century, very American “Shakespeare of rock and roll” (Dylan), Chuck Berry.

The song, with its enchanting melody, is an instant success. Alone in the year of its release, 1965, seven covers are recorded, of which Barry “Eve Of Destruction” McGuire’s is the best known. Attractive drive, beautiful harmonica solo, but the affectionate vocals and Barry’s artificial recital do not stand the test of time. Then the chaotic, disrespectful cover of the weirdos from The West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band (also ’66) is more bearable – but equally dated.

Most charmed, Dylan himself undoubtedly is by Rick Nelson’s cover (Rick Nelson And The Stone Canyon Band, 1969), given his appreciative words in Chronicles:

“Ricky’s talent was very accessible to me. I felt we had a lot in common. In a few years’ time he’d record some of my songs, make them sound like they were his own, like he had written them himself. He eventually did write one himself and mentioned my name in it.”

Ricky scores a small hit with it, but this cover really is a bit too unimaginative. In that area The Nice, also in 1969, is doing better. In which regard they do have an obligation, of course, being a progrock group and all. Theatrical and with a spun-out, Teutonic middle part they stretch the song to twelve minutes, but it still has an equally fascinating, magnetic appeal as, for example, the cover of Simon & Garfunkel’s “59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy)” on The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper.

Tina Turner turns it into “He Belongs To Me”, the Grateful Dead loves the song and has been playing it since the first concerts in 1966, it is popular in folk, country and rock circles, is translated all over the world – “Elle m’appartient (C’est une artiste)” by Francis Cabrel from 2008 is the most beautiful – and Dylan cherishes the song too; in 2016 it is still on his set list (46 times even), thus making Olof Björner’s list of Songs Performed More Than 500 Times.

The best cover comes from Norway. Ane Brun is blessed with an unearthly voice (and was rightly recruited by Peter Gabriel as a backing vocalist), and does everything you have to do if you dare to do a Dylan cover: an idiosyncratic approach, respect for the original and an enriching je-ne-sais quoi.

Recorded for one of the best Dylan tribute records of this century, Subterranean Homesick Blues: A Tribute To Bob Dylan’s ‘Bringing It All Back Home’ (2010), performed by artists who weren’t born yet when Dylan released Bringing It All Back Home – all of them artists who, thankfully, do look back on this walking antique.

———–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

Dylan’s twist on Berry’s song is that the gal is nobody’s child – she’s of legal age- with a mind of her own – an archetype – no where does Dylan say, like Berry does, that she’s six years old….Dylan varies on a theme ….he decides not to wait and leaves a trumpet and drums at her gate.

And let’s not forget the fairy tale that I’ve previously mentioned about the prince who peeks through the key hole at the usually donkey-skinned princess who then drops her ring into the food she cooks for the love-sick prince.