by Jochen Markhorst

I A bloody mess

Oh Mercy! is quite a beautiful album anyhow. Otherwise we would have been forced to impose a serious reprimand on Dylan for omitting the masterpieces “Series Of Dreams”, “Born In Time” and “Dignity”. One reproach can still be made, though: “Dignity” would have been a much more successful opening than the equally driving, but melodic and lyrically much less catchy “Political World” – great song, but hardly as monumental as “Dignity”.

Oh Mercy! is quite a beautiful album anyhow. Otherwise we would have been forced to impose a serious reprimand on Dylan for omitting the masterpieces “Series Of Dreams”, “Born In Time” and “Dignity”. One reproach can still be made, though: “Dignity” would have been a much more successful opening than the equally driving, but melodic and lyrically much less catchy “Political World” – great song, but hardly as monumental as “Dignity”.

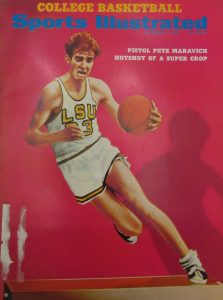

In Chronicles the bard remembers the rise and fall of the song. As usual crystal clear, yet incomprehensible. He describes how he is shocked by the news flash on the radio about the sudden death of the basketball player ‘Pistol’ Pete Maravich, whom he admires († 5 January 1988) and writes the whole song (and more) in a kind of inspired frenzy in the course of the same day and following night. “It’s like I saw the song up in front of me.” That primeval version is a bit longer, with even more archetypes, he tells. Big Ben, Virgin Mary, the Wrong Man and more: “The list could be endless.”

However, the connection between the legendary basketball player or his death with one of these characters, or with the theme of the song lyrics at all, remains unfathomable.

While writing, Dylan already hears the music in his head, too. Rhythm, tempo, melody line, everything. And He saw that it was good: “This song was a good thing to have.” He is in no hurry recording it, though. A song like this he won’t forget, he knows, and recording it is so boring. What’s more: “I didn’t like the current sounds.”

All of a sudden there appears to be a sharper discernment than we are used to from the man who, in this decade, doesn’t think recordings of brilliants like “Angelina”, “Caribbean Wind” and “Blind Willie McTell” are good enough. Fear of the disastrous effect of the 80’s sauce over a song like “Dignity” is indeed justified and it is to be applauded that the bard prefers to wait for better times with a fresh producer.

He does not have to wait very long. Just over a year later, in February 1989, better times have come, and a skilful, passionate producer has been found: Daniel Lanois.

Dylan will provide a series of beautiful recordings for Oh Mercy. And indeed, Dylan hasn’t forgotten “Dignity”; it’s one of the first songs of which a demo will be made.

Things are going well until then, at least: according to the chronicler himself. There’s nothing wrong with a first, sparingly instrumented recording with the vocals up front, he thinks, but an infectiously enthusiastic Lanois has some wild dreams about what he can achieve with this song when they record it tomorrow with Rockin’ Dopsie and his Cajun Band. Dylan lets himself be convinced.

And that is where the downfall of “Dignity” begins. After a day of muddling through text changes, tempo modifications and alternative keys, and after more than twenty recordings, the promise “was beaten into a bloody mess”. Disillusioned, Lanois and Dylan turn away from the song. The demo and one of the many outtakes can later be found on Tell Tale Signs (2008), others on bootlegs like Deeds Of Mercy and The Genuine Bootleg Series.

After Oh Mercy the song seems to be forgotten for a while, but in ’94 it reappears at the MTV Unplugged sessions. At the time ignored and even vilified, for obscure reasons, but as a matter of fact still very enjoyable today.

The same goes for the version used for Greatest Hits Vol. III (November ’94). Producer Brendan O’Brien (from, among others, Pearl Jam) waltzes off with the Lanois recordings, throws away everything except the voice and puts his own beautiful organ under it. This version also receives all the (un)necessary criticism, which from a present-day point of view seems just as empty; it really is a beautiful, “dry” recording, exciting and subdued at the same time. Dylan himself seems to think so too; a lot of (and the best, actually) live performances in the Never Ending Tour are grafted onto this version – with the troubadour singing better and better, too.

MTV Unplugged

The lyrics are from a Dylan at the top of his game. Fascinating, rich and mysterious, and by all means comparable to a highlight like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: a collage of unrelated images, half-known cinematic fragments, literary references, cool humour and biblical imagery, which together sketch a gloomy, grim world view in which there is no place for Dignity.

The images are connected by a literary stylistic device we don’t encounter too often in Dylan’s oeuvre: the allegory, the personified abstraction, in this case Dignity. The narrator searches from Alaska (“The land of the midnight sun”) to the Valley of the Dry Bones (from one of Dylan’s favourite Bible books, Ezekiel), searches in literary masterpieces (in Rimbaud’s Le Bateau ivre, among others) and everyone he meets along the way is also looking for her – in vain. He is stranded on the shore of a lake and seems to give up – in this world he will no longer find Dignity. Gloomy indeed.

Fortunately, the music offers hope. It pushes forwards, expresses optimism and does not fade away – on the other side of the lake we will resume our quest.

A strong unity apparently, the lyrics and the music. The covers seldom deviate, do imitate the compelling urgency of the rhythm and tempo of the original and copy remarkably often percussion guitar and organ (Joe Cocker, the French “La Dignité” from Francis Cabrel, the splendid Italian “Dignità” by Francesco Di Gregori). Even the implausible Nana Mouskouri adheres to this format (1997), puts a pleasant piano part under it, and then confirms the prejudices by inviting a gruesome women’s choir into the studio.

Elliot Murphy does not fall for that trap. His version is beautiful but doesn’t really add anything (on the “Reporters sans frontiers” album Dignity, 2002).

Robyn Hitchcock, in contrast, does his utmost best to be original, but unfortunately – he produces a weird, monotonous cover that only gets some attraction halfway, when the bass joins in.

No, the best cover is recorded in Amsterdam, by The Low Anthem (2 Meter Sessions, 2009). The quintet from Rhode Island leaves the ambiguous character of the song for what it is and opts for a one-dimensional, text-oriented acoustic interpretation that shines thanks to a gloomy clarinet. Singer Ben Knox Miller browses the different versions in a seemingly random way, choosing the verses he likes the most, messing up the order as well.

Surely the master will allow all that – Ben Knox Miller is, after all, a young man lookin’ in the shadows that pass.

To be continued. Next up: Dignity part II: Blades

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down