Details of all the articles in this series on the art work on Dylan’s albums can be found here

By Patrick Roefflaer

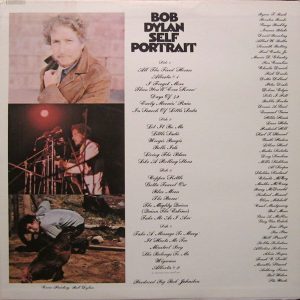

- Released: July 8, 1970

- Painter: Bob Dylan

- Photographers: Al Clayton, John Cohen and David Redfern

- Art-director: Ron Coro

Bob Dylan’s tenth album, Self Portrait, was his second double album (after Blonde on Blonde). While he made the painting for the front cover himself, no fewer than three photographers were needed to make the artwork for its gate fold sleeve.

Bob Dylan’s tenth album, Self Portrait, was his second double album (after Blonde on Blonde). While he made the painting for the front cover himself, no fewer than three photographers were needed to make the artwork for its gate fold sleeve.

Photographer 1: Al Clayton

In 1969, Al Clayton almost got to deliver the photo for the front cover of Nashville Skyline. At that time, the photographer’s first contact with the singer had been rather difficult (see https://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/12600) . That changed shortly afterwards.

On May 1, 1969, Dylan is back in Nashville. He is invited by Johnny Cash, who wants him to take part in The Johnny Cash Show. Filming of new TV series takes place in the Ryman Auditorium, the legendary theatre from which the Grand Ole Opry has been broadcast weekly since 1943. For each episode, Cash is free to invite some guests. For the very first broadcast these are: Cajun fiddler Doug Kershaw, the young folk singer Joni Mitchell and his friend Bob Dylan.

An article on the footage published in Rolling Stone on June 1, 1969, states:

“After the concert, a photographer said to him, “You looked nervous today, Bob. ”

“I was terrified,” he replied, smiling.

The author, Patrick Thomas, probably had no idea that Dylan meant it literally.

Al Clayton explains what happened: “We were all in the locker room when suddenly someone fell through the roof. The man tried to get in like that. Poor Dylan shouted, ‘Al, get him out of here!’ The police came and took him. After that, Dylan was nice to me. I think he trusted me.”

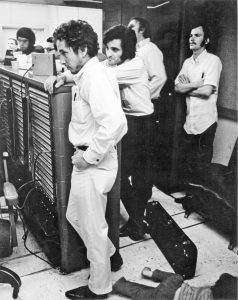

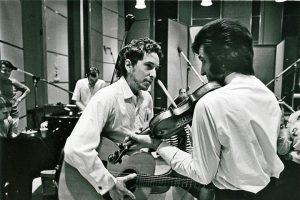

Two days after the filming, Clayton is also present in the Nashville studio during the (for now) last session for Dylan’s next album.

Doug Kershaw has also been invited to spice up the recordings of some covers of country songs with his fiddle: ‘Take A Message To Mary’, the classic ‘Blue Moon’ plus two songs by Johnny Cash.

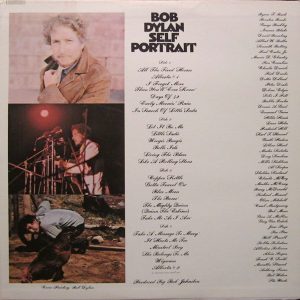

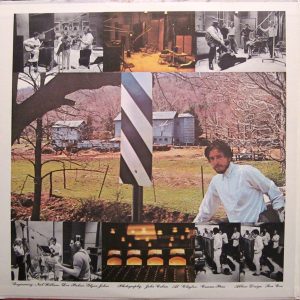

The left side of the inner sleeve of Self Portrait contains seven photos from this session. In the five black and white photos, Dylan is at work.

In two of them, where he the musicians are listening to a playback, Dylan’s son Jesse can be seen playing on the floor.

In addition of these black and white pictures, there are two color photographs: one of the empty Columbia Studio A and one of the mixing console.

Photographer 2: David Redfern

On the right side of the inner sleeve, there’s a list of the songs and all the people involved in the sessions. There are also three more color photos. The one in the middle is one of Bob Dylan performing at the Isle of Wight Festival on August 31. 1969. It was his first live gig since the end of his World Tour, on May 27, 1966.

This portrait is the work of the David Redfern.

The Brit was specialized in immortalizing performances by jazz musicians. He stood out among his colleagues, because unlike most of them, he used color film. He was so good at his job that when the American Postal Service issued ten stamps dedicated to jazz musicians in the 1990s, three of them were based on his photos.

His reputation as the ‘Cartier Bresson of jazz’ earned him invitations to the major jazz festivals in Newport, New Orleans and Montreux, before expanding to the major rock festivals, including that on the Isle of Wight, where he captured Dylan alone with his acoustic guitar, in front of a lot of microphones.

Photographer 3: John Cohen

The two other color photo’s on the left side, and the center picture on the right side are all by a third photographer, John Cohen.

Cohen was a musicologist and musician, as well as a photographer and filmmaker. He founded the New Lost City Ramblers in 1958 with Mike Seeger and Tom Paley, a string band that aimed to bring the sound of old-time Appalachian music back to life. For this they wanted to return to the source, by looking for living musicians who made recordings in the 1920s and 1930s. The kind of people that were later collected by Harry Smith on Anthology of American Folk Music. Cohen made images of this quest, which he later bundled in the film High Lonesome Sound (1962).

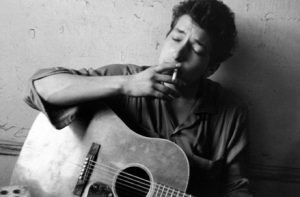

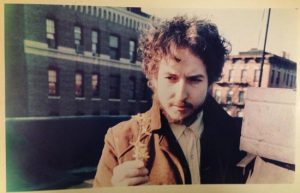

“I first met Bob when he first came to New York in 1961”, Cohen recalled later, “in one of the coffee houses near where he lived in Greenwich Village”.

In the spring of 1962, Cohen was asked to have a photoshoot with the Bob Dylan, for an article on the young singer. He invited the young singer to his loft in the East Village of New York City. They decided that they wouldn’t be disturbed on the roof of the 3-story apartment building, where Bob posed with his guitar and harmonica.

“I made a lot of photographs of him in black and white. There’s a famous one of him puffing a cigarette with a very anguished expression. I was seeing Woody Guthrie, of course, and Charlie Chaplin, because Bob was a very funny guy, but I was also seeing James Dean: there was an anguished, teenage look about him.”

In the spring of 1962, Cohen was asked to have a photoshoot with the Bob Dylan, for an article on the young singer. He invited the young singer to his loft in the East Village of New York City. They decided that they wouldn’t be disturbed on the roof of the 3-story apartment building, where Bob posed with his guitar and harmonica.

In the spring of 1962, Cohen was asked to have a photoshoot with the Bob Dylan, for an article on the young singer. He invited the young singer to his loft in the East Village of New York City. They decided that they wouldn’t be disturbed on the roof of the 3-story apartment building, where Bob posed with his guitar and harmonica.

In the spring of 1962, Cohen was asked to have a photoshoot with the Bob Dylan, for an article on the young singer. He invited the young singer to his loft in the East Village of New York City. They decided that they wouldn’t be disturbed on the roof of the 3-story apartment building, where Bob posed with his guitar and harmonica.

“I made a lot of photographs of him in black and white. There’s a famous one of him puffing a cigarette with a very anguished expression. I was seeing Woody Guthrie, of course, and Charlie Chaplin, because Bob was a very funny guy, but I was also seeing James Dean: there was an anguished, teenage look about him.”

Eight years after that first photo shoot, Cohen suddenly got that call from Bob Dylan.

In January 1970, Dylan had moved back to New York to escape overly pushy fans who traveled to Woodstock, to search for the singer and his family. Since moving to a remote place apparently didn’t help, the singer decided try hiding in plain sight and got back to the big city.

To find out if that worked, he enlisted the help of an old friend. “Hey John, I need some more pictures. Come to the city, but bring one of those lens like a telescope, so you can take pictures from a couple of blocks away.”

Armed with a rented tele-photo lens, Cohen headed to Dylan’s house on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. According to Howard Sounes (Down the Highway: The Life of Bob Dylan), Dylan owned the whole double townhouse. The Dylan family lived on the top floors, and they had tenants in the lower floors.

Perhaps for old time’s sake, the photo session started… on the roof.

“As we climbed up the ladder to access his roof, he took some forsythia flowers from a vase on his table. You can date the photos precisely by when forsythias bloom in NYC.”

These pictures were taken with a normal lens.

Then the “telescope” was needed, as Dylan wanted to know if he could blend in with the crowd. To find this out, they hit the street. The plan was for Dylan to just walk down to Houston Street, and Cohen would follow him from a great distance. Dylan. “I was mostly intuitive,” Cohen says, “because I couldn’t communicate with Bob from such a distance. He was walking around because I tried to see him. They were spontaneous compositions – there was no question of careful focusing. … He was alone and no one looked at him. He went unnoticed, was not recognized.”

In the first group of photo’s, he is carrying a drum. There are rumors that Dylan had a small recording studio on Houston Street during these years, where he then dropped the drum off. On the last photos, taken on the southeast corner of Houston Street where it meets Sixth Avenue (the ever reliable John Egan of PopSpots has identified the exact location), he no longer has the drum.

A week later they meet again, this time at Cohen’s house, on his farm in Putnam County – an hour’s drive from downtown NY. “He drove up and we had a couple of hours together. He was more self-contained than when I’d first met him, but he was always open to the shots that I suggested. […] He put on an old hat of mine (“Is that a hat? I don’t really wear hats.“), played around with my dog, got on his knees for some chickens and my kids, visited a nearby stable and some abandoned cars in the forest and admired some trees – very ordinary things that I do every day. It seemed as if I took pictures of myself in my own world with Bob as a stand-in for myself. ”

“I didn’t ask what he meant with these images and was very surprised to see them on the cover of Self Portrait.”

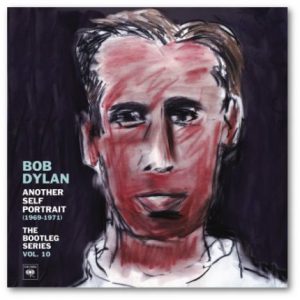

Dylan took the negatives and never returned them. It is not until some 40 years later that Cohen got to see the Ektachrome slides again during preparations for The Bootleg Series Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (1969–1971) In the Deluxe Edition of that set, released in August 2013, over 60 of Cohen’s photographs from Spring 1970 were published in the accompanying book

This lead to two exhibition of Cohen’s work, one in New York and another in Los Angeles, both called: Been Here and Gone: Photographs by John Cohen of Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie. To promote these, he told the story of his three photo shoots with Bob Dylan in various newspaper articles.

Painter: Bob Dylan

Both sessions with Cohen can be seen as an exercises in being present, without being visible. Immerse yourself in the crowd and use the world of another as if it were his own life in Woodstock. “Je est un autre”, as Arthur Rimbaud already knew.

Just as he used songs written by others to define an image of himself.

The painting he did of an unknown man can be seen entirely in the same vein.

“Someone I knew had some paint and a square canvas,” he explained casually. “With that I made that portrait for the cover in about five minutes. I thought, “I call this album Self Portrait.”

Just like on Nashville Skyline, the cover of Self Portrait lacks a title and name of the artist.

It’s difficult to present an album more anonymous.

Hiding in plain sight.

It almost goes without saying that the Bootleg Series edition dedicated to the Self Portrait period features a new portrait of another unknown man.

12 years of Untold Dylan

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

in the summer of 72 I happened to visit Bob’s house on Ohayo Mt. Road just outside of and up the hill from Woodstock. as i had been told by a local i would know Bob’s lane by a sign that said, Children at Play. Seeing that sign, i turned inside and the wooded lane opened onto a meadow with the brown shingle house sitting there. no dogs; no guards. only one car. A yellow lotus Europa. To the right of the front door was a large bay window with an easel and some canvases. i have assumed this is probably where Bob had painted the ‘self portrait.” When i knocked on the door a man answered and asked what i wanted. i asked him if this was Bob Dylan’s house and he said it was. he told me to wait there and i could hear him talking quietly to another man. I assume now that was Dylan. i stepped just inside the door and saw a room on the left with piano and a guitar on the wall. kids toys were everywhere. The man came back with a note pad and asked me to leave a message for Bob. Which i did. he said I could not come into the house. But he was very polite. The other man never appeared. The man, Walter Johnson told me to wait and he would give me a ride back to town. So I walked past that big bay window and looked at the paintings, then around the right side of the house and looked in the kitchen door with screen pushed out by children. in back was a swimming pool. But it was not a fancy kind of place. it was an inviting kind of rustic place. The pool almost didn’t fit in. I’m sure i was being watched but i was not a dangerous person and there was no sign of other fans. it was very beautiful. When I got back to the front we got into the Lotus and Walter took me down to the freeway. I had to get out of the car in a rain that had begun. Walter told me about Bob a bit and visits by George Harrison. i never asked him about the other man in the house. i think the family were probably in NYC and Bob was there at this house on Ohayo mt. road. It was not my intention of intruding on Dylan. I just wanted to say hello and I have enjoyed you since I was a boy. Ironically, years later I met Dylan and got to talk to him alone. I never mentioned this incident. He was nice and we shook hands. I love the SP record and many of the songs of that period including New Morning. I have never read about anyone else who went to that house. Only heard Dylan say that people came. I was well treated by Walter—and Bob. No police came, no dogs, no threats at all. Simply, Yes, this is Bob Dylan’s house. it is a very fond memory. i enjoyed reading this article.

David, thanks for sharing your story.