by Patrick Roefflaer

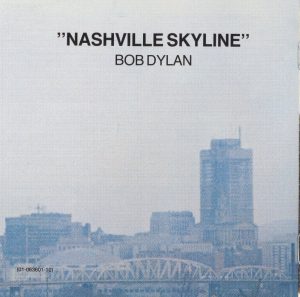

- Released: April 9, 1969

- Photographer front: Elliott Landy

- Liner Notes: Johnny Cash

- Photographer back: Al Clayton

- Art-director ?

Al Clayton

In 1956, Al Clayton was a third-year medical student in the Navy. When he was handed a camera to capture an operation, he appeared to have talent for it and continued his education at the US Navy Medical Photography School to become a medical photographer. After his release from the army, he continued his studies at the Los Angeles art school and then settled in 1963 as a photographer in Nashville.

In the mid-sixties he travelled through the Mississippi Delta, eastern Kentucky, Georgia and Alabama, where he documented poverty.

His photos were used in July 67 to encourage senators to start an anti-poverty program.

Two years later the photos appeared in a book: Still Hungry In America.

Johnny Cash got impressed by the book and befriended the photographer. In mid-February 1969, he was invited to a party, Cash gave at his house on Cumberland River in Nashville. Among the guests: Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury and Bob Dylan, who was in town to record the songs for his next album. “Bob and Sara and the kids stayed at my house while he was recording that record,” Cash explained.

Approaching Dylan wasn’t obvious, the photographer experienced. In an interview published in The Sunday Times (August 2013), Clayton recounted: “Dylan was unusual. My first impression was of an extremely shy person; he seemed on the edge of paranoia, really frightened. We didn’t get into what he was frightened of — it would be very deep, I think, psychologically. I tried to talk to him, but whenever I would bring up a topic, he would say: “I don’t know anything about that.” He was completely withdrawn, and very unto himself.”

However, Clayton saw an opportunity and send Dylan some of his photos.

However, Clayton saw an opportunity and send Dylan some of his photos.

Among them was one of the city skyline, which impressed the singer so much that he chose it for the cover of his album.

The photo even provided him with the title: Nashville Skyline.

Sometimes life can be easy.

Elliott Landy

Johnny Cash provided a poem to be printed on the back cover.

Because the skyline picture on the front is very anonymous, the art-director of the record company asks for a portrait of the singer, to appear next to Cash’s poem.

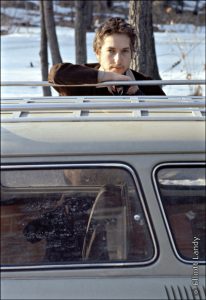

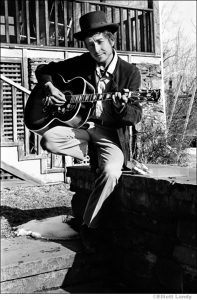

Bob Dylan, outside my home, Nashville Skyline photo sessions, Woodstock, NY, 1969. Photo By ©Elliott Landy, LandyVision Inc.

As it happens, there’s a photographer who recently moved to Woodstock, where Dylan and his family are living. Elliot Landy caught Dylan’s attention with the photos he made for The Band’s debut album.

In his book Woodstock Vision (1994), Elliott Landy explains how the photo came about. “In early 1969 he called and asked me to take a picture for the back of his new album, Nashville Skyline. He had the front cover already picked out—a picture of the skyline of Nashville, where he had recorded the album.

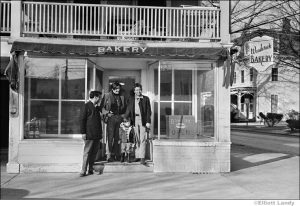

We didn’t know what to do; we had no concepts when we started. We met, and he suggested that we take a picture in front of the bakery in Woodstock with his son, Jesse, and two local Woodstock people. The brown leather jacket he was wearing was the same one he had worn for the covers of John Wesley Harding and Blonde on Blonde.

He was still uncomfortable being photographed, and therefore I was uncomfortable photographing him, but we stayed with it. We took some pictures at the bakery and then went to my house and hung out.”

But then Dylan has second thoughts. He doesn’t want to draw attention to his son.

A new appointment is arranged. This time the photographer can visit Dylan at home, in Byrdcliff. (Did you know that Dylan’s house, Hi Lo Ha, is now owned by Donald Fagen of Steely Dan?)

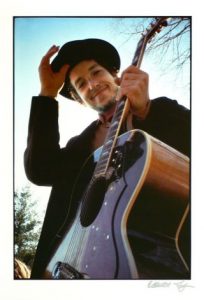

That morning it has snowed, but in the afternoon the sun broke through. That is why the photographer proposes to go outside. Because it is wet, Dylan puts on boots. He takes a guitar he has received from George Harrison as a gift and… “As we left the house, he grabbed a hat, and asked, “Do you think we could use this?” I had no idea if it would be good or not, so I told him “take it, and we’ll see.”

They head for the woods behind his house in search of a nice location.

They head for the woods behind his house in search of a nice location.

“He paused for a moment, apparently inspired, and said, “What about taking one from down there?“ pointing to the ground.

As I started kneeling, I saw that it was muddy but kept going. ”Do you think I should wear this?“ he asked, starting to put on his hat, smiling because it was kind of a goof, and he was having fun visualizing himself in this silly-looking trad itional hat.

itional hat.

”I don’t know,“ I said as I snapped the shutter. It all happened so fast. If I had had any resistance in me, I would have missed the photograph that became the cover of Nashville Skyline. It is best to be open to life.”

When Dylan sees the photographs, he decides that this will be the cover photo.

He explicitly asks that nothing be added – no name, no title, nothing.

“This was Bob’s way of saying that his music was not created as a commercial pursuit,” Landy offers.

Nevertheless, CBS puts the logo in the  upper left-hand corner.

upper left-hand corner.

Landy is quite disappointed: “Although small and seemingly insignificant, this ruins the three-dimensionality of the image.

While looking at the record, cover the logo, then uncover and cover it again.

It will appear to go from two to three dimensions and back.”

Eric von Schmidt

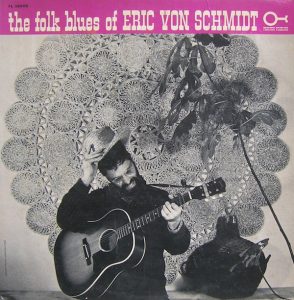

Soon people noticed the similarity of Dylan’s pose on the photo with that of Eric von Schmidt on The Folk Blues or Eric von Schmidt.

The fact that the 1963 album can be seen as one of the objects on the cover of Bringing It All Back Home indicates that Dylan was familiar with the image.

The choice for just this photo can therefore not be a coincidence.

Hence perhaps Dyla n’s smile when he suggested taking that picture. Dylan’s admiration for the singer was already apparent from the name check he gave at the spoken intro of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” on his debut keynote.

n’s smile when he suggested taking that picture. Dylan’s admiration for the singer was already apparent from the name check he gave at the spoken intro of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” on his debut keynote.

Moreover, later in 1969 Dylan writes the cover text for von Schmidt’s album Who Knocked the Brains Out of The Sky?.

He calls him: “… a man who can sing the bird off the wire and the rubber off the tire.” To conclude with “he is also a hell of a guy.” – a clear reference to Cash’s poem on his Nashville’s own Skyline in which the Man in Black praises Dylan as “a hell of a poet.”

Other articles in the series

- The untold story of the artwork on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- The Sleeve Art of Bob Dylan’s album: “Bob Dylan”

- The Sleeve Art of Bob Dylan’s Album: Slow Train Coming

- The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan – the untold story of the artwork of the album

- Times they are a changin’: the album artwork

- The art work on Bob Dylan’s albums: The Basement Tapes

- The source of the artwork of “Another side of Bob Dylan”

- The art work on Bob Dylan’s “Infidels”: what’s in a name?

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 594 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

Bob Johnston was the art director! My father was Al Clayton. 🙂

I don’t doubt the Von Schmidt connection, but check out Sonny Boy Williamson’s ‘Keep It To Ourselves” album — it’s a new release (1990) but obviously an old photo since he died in 1965. It’s been used on many recent compilations but doesn’t seem to have been used on any releases running up to the Schmidt or Nashville records, so hard to know if it had been seen at that point.

Maybe it was a familiar visual motif back then — smile, tip of the hat and instrument.